The war in Ukraine continues to disrupt the country’s agrifood sector, posing an ongoing threat to food security. Damage to critical infrastructure is hindering agricultural activity and the transportation of essential food to local markets and to export destinations. This situation, together with destroyed livelihoods and high inflation, is hampering access to food for millions of Ukrainians.

More than 7 million Ukrainians face acute food insecurity

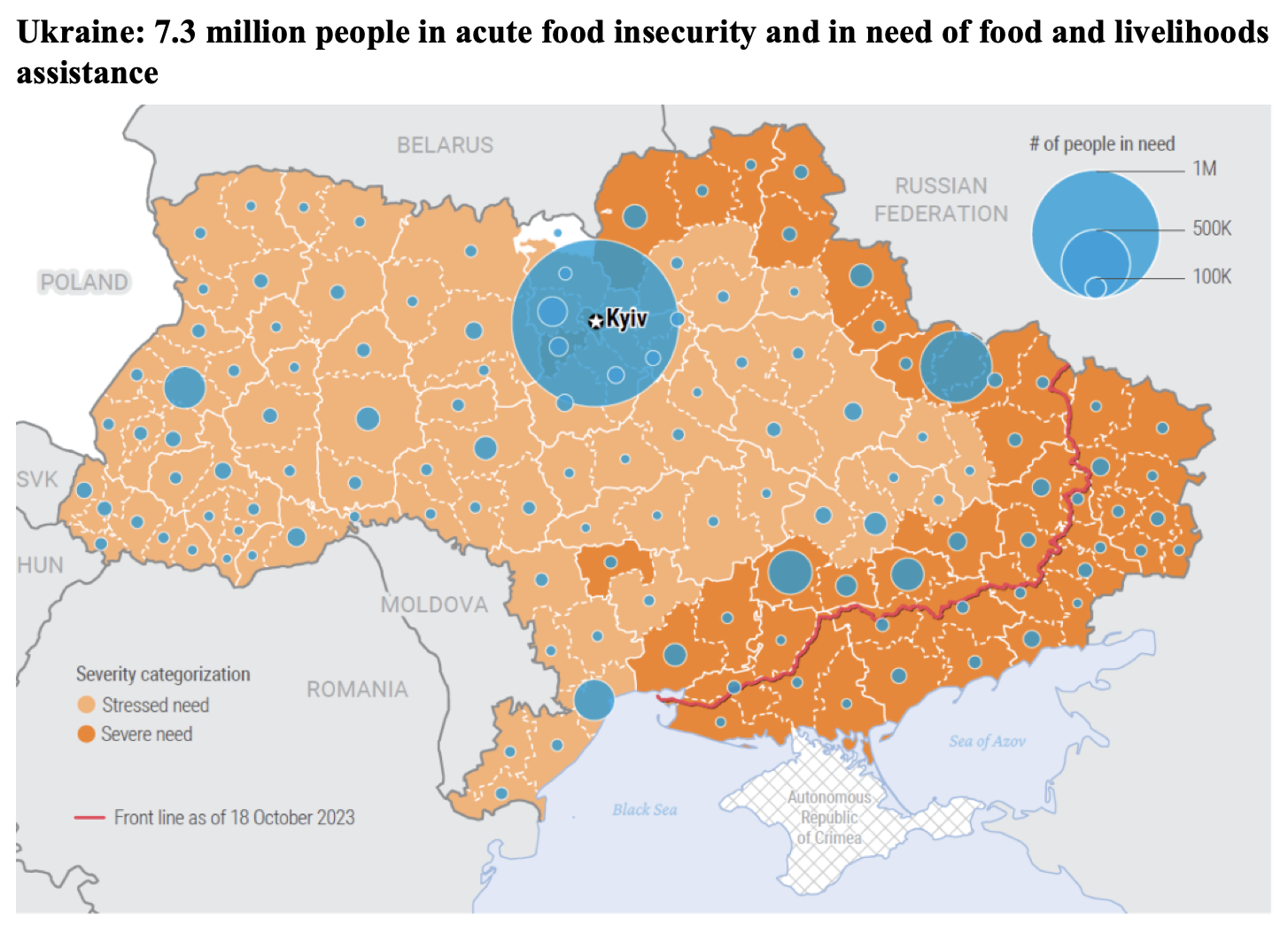

An estimated 7.3 million Ukrainians (20% of the population excluding those in the Russian-occupied areas) face moderate or severe food insecurity, including 1.2 million children and 2 million elderly, according to an analysis by the Ukraine Food Security & Livelihoods Cluster, led by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA) and the World Food Programme.

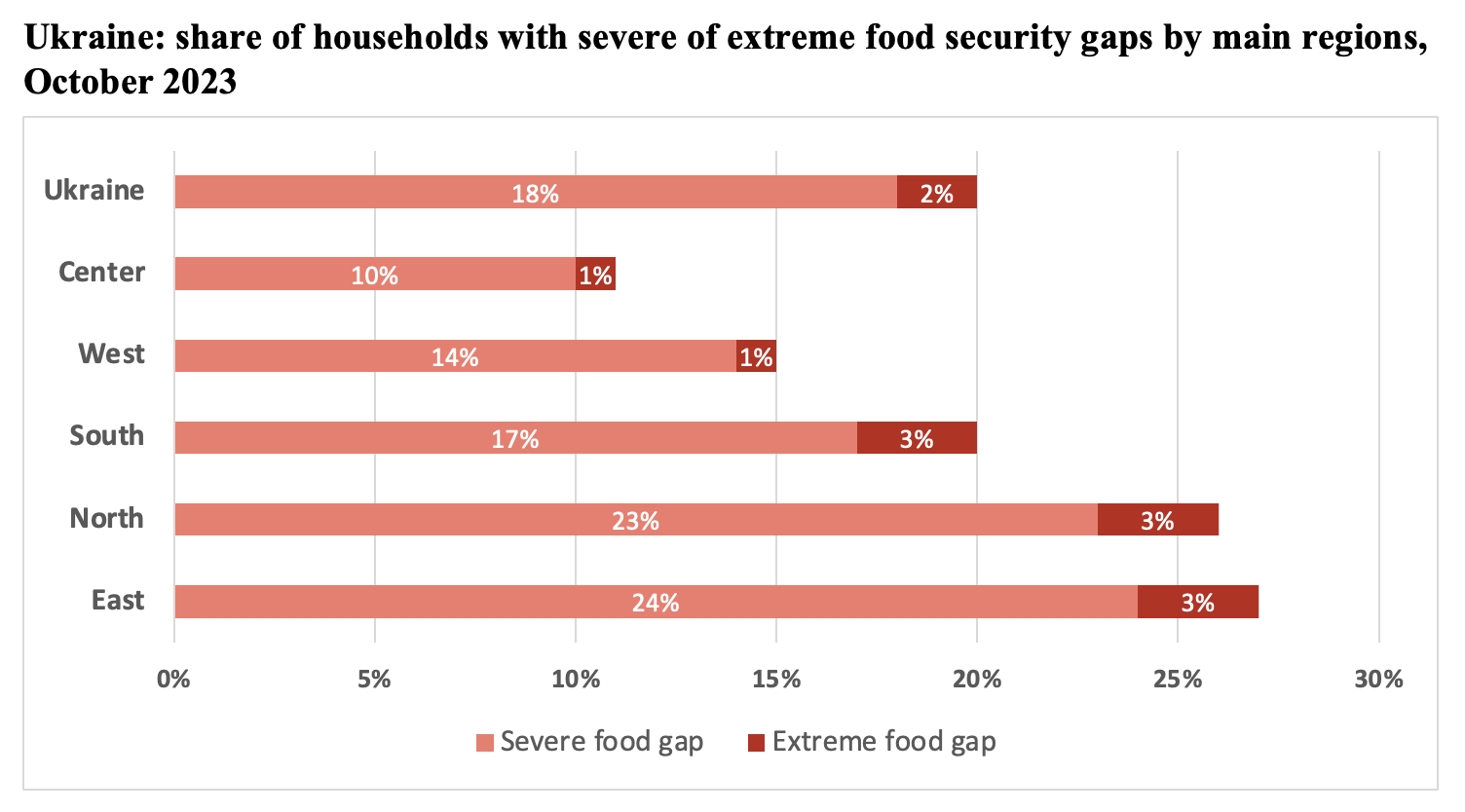

This makes Ukraine one of the largest current food crises by absolute numbers of acute food-insecure people requiring food and livelihoods assistance. Among them are also about 1 million returning refugees and nearly 1 million internally displaced Ukrainians. While there is also a high concentration of food-insecure people in Kyiv, the capital, most of the affected are near the war’s front lines in Ukraine’s east and north, where 27% and 25% of households, respectively, were found to face severe or extreme food deficits (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

Source: UN OCHA, World Food Programme et al., the Ukraine Food Security & Livelihoods Cluster.

Figure 2

Source: UNOCHA, Ukraine Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan 2024

Ukraine’s current food insecurity problems first emerged following Russia’s 2014 occupation of Crimea and the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. When Russia’s 2022 invasion began, the latter two were already classified in the semi-annual Global Report on Food Crises as contexts of “major food crisis” with more than 1 million people facing acute food insecurity. The severity and magnitude of the food crisis worsened dramatically with the start of full-fledged war in February 2022. Ukraine’s agrifood sector has suffered massive losses that have negatively impacted crop and livestock activities that have reverberated through global markets.

Coping strategies

The war has displaced an estimated 3.7 million Ukrainians. About half originate from the oblasts of Donetsk (occupied by Russia) and Kharkiv (near the front in the country’s northeast). The internally displaced people are most in need of financial support to access food, having lost their livelihoods. Access to humanitarian assistance is very limited in the areas currently under Russian military control and near the front lines. As a result, many displaced people are coping by switching to cheaper food and non-food items, reducing the quantity of food consumed, relying on savings if they have them or selling assets when running out. These coping strategies also predominate among non-displaced food-insecure households.

Some economic improvement during 2023 despite continued low farm profitability

Despite the ongoing fighting and a Russian bombing campaign, livelihood conditions have seen some recent improvements. While still very high, the number of food insecure people declined during 2023 by 1.6 million (down from an estimated 8.9 million in 2022), according to the 2024 Humanitarian Response Plan for Ukraine. Macroeconomic conditions have improved, with Ukraine’s economy somewhat recovered from the deep recession in 2022. After dropping by 30% in 2022, real GDP increased by 5.7% in 2023. Inflationary pressures eased, with overall inflation falling to pre-war levels of 4%-5% annually. Food price inflation also softened, falling from a peak of 35% at the end of 2022 to under 10% in the second half of 2023, then easing further to 3% (year over year) in February 2024 (Figure 3). Food price inflation could be contained in good part because of favorable weather conditions and higher crop production.

Figure 3

In the 2023-24 harvest season, production of major crops (wheat, maize, barley, sunflower and rapeseeds) increased compared to year following the invasion (Figures 4, 5, and 6), though remain still well below pre-war levels of 2016-2021.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

For wheat and maize, the harvested area decreased further in 2023-24, but—consequently—yields increased. In the case of wheat in particular, farmers are adapting to the war context by shifting what is planted and when. In the Russian-occupied oblasts, farmers primarily sowed winter crops (wheat), while those in government-controlled areas shifted toward sunflower and rapeseed, which require fewer inputs and have lower energy costs than wheat (NASA Harvest, December 2023). These production shifts seem to align with a recent official assessment by the Ukraine Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food and the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club indicating that, despite the recent recovery in production, grain cultivation remains generally not profitable as international prices have fallen while production and logistics costs remain high.

In the case of wheat, an important caveat is that near 30% of the crop’s 2023 output was produced in the Russian-occupied eastern oblasts, and thus overall agricultural production on Ukraine-controlled soils remained below 2021 levels and the five-year pre-war average (NASA Harvest, December 2023).

Compared with grains, the profitability of oil crop cultivation has been somewhat better, the Ukrainian official assessment also indicates, which could explain in part the expanded planting of sunflower and rapeseed during the 2023-24 season. Oil seed farm prices were less affected than those of grains, owing in part to increased demand from vegetable oil processors in other countries. To meet the demand, Ukrainian farmers have outsourced processing, sending uncrushed sunflower seeds to buyers who process the oil out of the country, as the war has damaged Ukraine’s seed-crushing and processing infrastructure and dedicated sunflower-seed oil ports were closed.

Export problems caused additional disruptions. With Black Sea ports blocked during much of 2022 and good part of 2023, Ukraine was forced to export most of its production of grains, oilseeds, and other goods via EU-established solidarity lanes—land and river routes into neighboring countries to the west, where they could be exported elsewhere around the world.

However, the Ukrainian exports quickly overwhelmed rail, road, and river infrastructure in countries including Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, which had their own abundant inventories, and costs for exporting via the solidarity lanes spiked. As a result, Ukraine exports ended up being sold at low prices in the neighboring countries, triggering farmers’ protests and then import restrictions on Ukrainian products—further pushing down prices and farm profitability.

But exports of wheat, maize, and sunflower seeds recovered during 2023, helped not only by increased production but also the ability to ship from the seaports of the Odesa region again (first due to the Black Sea Grain Initiative, then, after that ended in July, due to improved Ukraine military control of the seas). In general, the first two months of 2024 were more successful for Ukraine’s agricultural sector than much of 2023. Thanks to improved conditions for exporting through the Black Sea, improved product prices and logistics, it became more attractive to use the ports in Ukraine than through the solidarity lanes.

Huge challenges remain

Despite these improvements, the challenges to Ukraine’s agriculture and its economy at large remain huge and will continue to threaten food access and availability in the country for years to come.

The ongoing war continues to disrupt Ukraine’s economy and agrifood sector, as air and ground attacks on civilians and infrastructure hinder most forms of economic activity. The physical damage to critical infrastructure, including homes, energy infrastructure, dams, ports, and warehouses, is not only constraining the availability of food in markets and eroding livelihood opportunities, but also causing the abandonment of farmland. Widespread damage to agricultural infrastructure—including grain storage facilities, irrigation systems, and farms—and the loss of agricultural machinery have disrupted supply chains and increased production costs. One of the more intense attacks on Ukraine’s agricultural assets was the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam eastern Ukraine in June 2023 (an action which a number of experts attributed to Russia, which Russia has denied). The resulting flood killed dozens across 46 towns and villages, forced thousands to flee, and destroyed much of the region’s agricultural infrastructure.

These and other damages and losses to Ukraine’s agriculture sector are changing the nature and scale of the country’s agricultural activities. The total cropland decreased by approximately 7% due to damage and abandonment caused by the war. This translates to an estimated $2 billion in lost harvest and a quantity of grains and oilseeds that could have fed over 25 million people for a year, according to NASA Harvest.

Total damage and losses to Ukrainian agriculture have reached $80 billion, with losses accounting for 87% of the total ($69.6 billion), according to the Third Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment for Ukraine (UA-RDNA3) conducted by the Government of Ukraine, the EU, World Bank, and the United Nations in February.

Losses include the loss of farm income, loss of production value due to lower farm gate prices caused by export logistics disruptions, higher farm production costs, and the cost of land recultivation after mine-related surveying, clearance, and land release operations. The decrease in annual crop production accounts for almost half of the estimated total agricultural losses.

Damages include the partial or complete destruction of storage facilities, fisheries and aquaculture, and perennial crops, as well as the forced slaughter of livestock, as well as the destruction and theft of machinery and equipment, inputs, and food stocks.

Significant international support needed to repair massive damage to agriculture and restore food security

These monetized losses are directly connected to the rise in food insecurity and erosion of livelihoods. The major drop in the profitability of agricultural production has reduced farmers’ incomes and the wages of millions of rural Ukrainians. Direct employment in the sector is estimated to have fallen by 18%, causing a stark decline in wages paid to farm workers.

The UA-RDNA3 estimates that—without further damages—more than $56 billion would be needed over the next 10 years for recovery and reconstruction of Ukraine’s production capacity and infrastructure. To ensure that the agricultural sector recovers to help drive overall economic recovery, provide decent income to farmers, and supply adequate amounts of food for the population, massive investments in the sector are needed to address liquidity constraints faced by farmers, enhance the climate resilience of agricultural production, restore irrigation and logistics infrastructure, integrate food-energy systems, and recover global market access.

While risky, such a reconstruction effort could start in the more secure parts of Ukraine before the war ends, but a resolution to the conflict that establishes security for the whole country will be needed to rebuild food systems across Ukraine. Only then can food security be restored in the country and the war’s effects on global food security ended.

Meanwhile, as the war continues to affect livelihoods, humanitarian support should be stepped up. In a concerted effort, the UN and other international and local humanitarian agencies now aim to reach 3.4 million food insecure people in Ukraine with immediate life-saving assistance, including both in-kind and market-based support (cash or vouchers) where appropriate and actions aimed at improving the self-reliance of vulnerable, war-affected households and communities in the nine oblasts with the highest prevalence of acute food insecurity. Targeted beneficiaries are to include almost 1 million internally displaced people and returning refugees who have lost their livelihoods. These efforts will be critical to avoid further and widespread human catastrophe in Ukraine. As the war continues wreaking havoc on livelihoods, the need for such support will only increase and, hence, should remain a priority for the international community.

Rob Vos is Director of IFPRI's Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit. Opinions are the author's.