Myanmar is undergoing rapid changes. The course of the COVID-19 pandemic there reflects this dynamic context, which is influencing both coronavirus transmission and its socio-economic impacts. A severe second wave of infections has led to lockdowns since mid-September—the second set of strict controls imposed after the initial outbreak in the spring. Derek Headey and colleagues have monitored monthly trends in poverty and food insecurity, and found the lockdowns have dramatic impacts. Based on those findings, they used micro-simulation methods to assess different social protection scenarios to address sharp spikes in poverty. The combination of surveys and simulations provides useful insights into addressing the evolving COVID-19 situation and how Myanmar’s government can address it.—John McDermott, series co-editor and Director, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

COVID-19-related trade disruptions hit several sectors in Myanmar as early as January, but it was the appearance of the country’s first cases in March and the subsequent lockdown in April that really hurt the economy. Non-essential businesses shut down, workers and traders could not leave home, and demand for labor dried up. The initial COVID-19 prevention measures worked well—resulting in only a few hundred infections in a country of over 50 million by June—but led to a sharp spike in poverty rates followed by a modest economic recovery in mid-2020. Now, the country faces a second, far worse phase of the crisis, with another wave of infections emerging in Rakhine in August and quickly spreading out of control to Yangon and other regions. Myanmar went from a few hundred confirmed cases in early August to more than 80,000 by late November, despite widespread lockdown measures starting in mid-September.

New results from a high-frequency IFPRI survey show that Myanmar’s second wave of COVID-19 is leading to far more severe and deeply worrying increases in poverty. In addition, simulation results suggest that lockdowns have especially disastrous impacts on poverty and should be accompanied by larger and better-targeted cash transfers if Myanmar is to successfully contain the economic destruction of COVID-19.

The study, from IFPRI’s Myanmar Agricultural Policy Support Activity (MAPSA), used both surveys and simulations to understand the multifaceted disruptions of COVID-19 in Myanmar. From June onwards, we surveyed 1,000 mothers in urban Yangon (Myanmar’s largest city and commercial center), and 1,000 mothers in the rural dry zone (a major agricultural production center to the northwest of Yangon). The COVID-19 Rural and Urban Food Security Survey (C19-RUFSS) covered a wide range of welfare measures in addition to access to COVID-19 emergency response interventions.

However, the geographic and demographic limitations of the survey prompted us to also use a microsimulation analysis of a nationally representative household survey from 2015, in which pre-COVID livelihoods were negatively shocked with lockdowns and trade and remittances disruptions, but also positively shocked with different levels of household cash transfers. Hence the phone survey tells us what is happening on the ground in 2020, while the simulations illustrate potential impacts on poverty in 2021 under different economic and social protection scenarios.

Survey-based evidence on poverty in Myanmar in 2020

The monthly phone survey suggests that income-based poverty soared between January and June during the first wave of COVID-19 disruptions (Figure 1), especially in Yangon where only 7% of surveyed households were poor in January, but 32% were poor in June. In the rural sample pre-COVID poverty was higher than in Yangon (25% in January), and also increased dramatically to 52% in June. Both rural and urban samples saw some improvement in July, but when the second wave of COVID-19 broke out in August, poverty had picked up again. By September, with infections spreading rampantly and stringent COVID-19 measures again being implemented, income-based poverty rose dramatically, from 29% to 59% in the Yangon sample, and from 52% to 66% in the rural sample. October’s continued lockdowns saw no improvement in poverty: Three in five households are now earning less than $1.90/day, and almost a third of our sample tells us they earned no income in the past month.

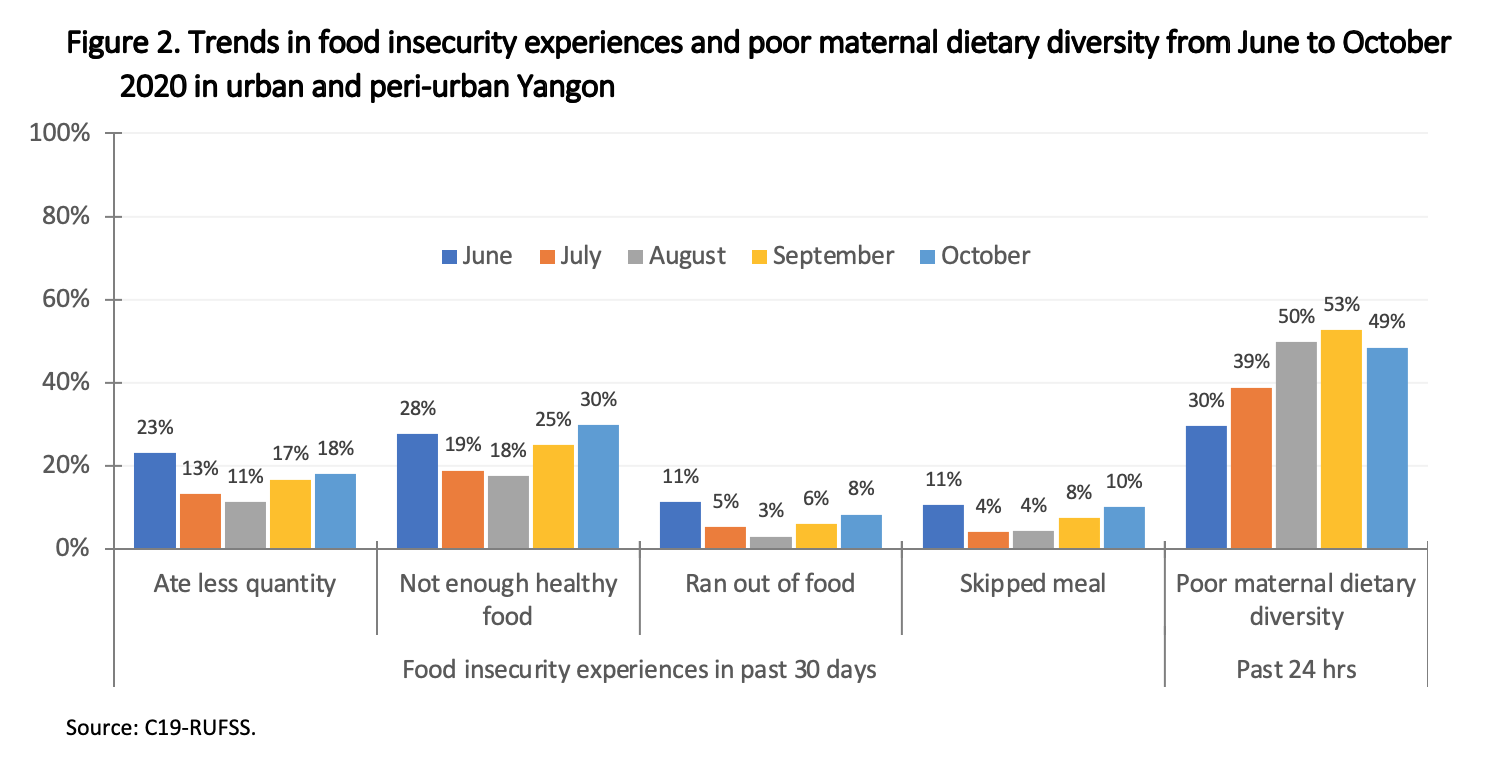

These poverty trends are also mirrored by rising rates of food insecurity and poor maternal dietary diversity, especially in Yangon (Figure 2). In the wake of the first wave, 28% of mothers in June reported not eating enough healthy food, and 30% had inadequately diverse diets. Food insecurity indicators improved somewhat in July and August, but deteriorated sharply again in September and October, while the share of urban mothers with inadequate diverse diets rose from 30% in June to around 50% from August to October.

Simulation-based evidence on poverty in Myanmar in 2021

With a prolonged and highly disruptive second wave, what should the government of Myanmar do to reduce poverty in 2021? Microsimulations can shed light on how poverty reacts to different degrees of COVID-19 disruptions, and different doses of accurately targeted cash transfers.

The simulation-based evidence tracks the survey results in showing that strict lockdown measures lead to sharp spikes in poverty. The simulations use an expenditure-based poverty measure at $2.50/day that allows for more consumption smoothing. This measure rises dramatically during lockdowns, especially in urban areas. Nationally, under this measurement, extreme poverty was 9.8% prior to COVID-19, but the simulation shows it rising to 31.6%, and urban poverty rising from just 2.7% to 24.7%, during strict lockdowns.

To address the economic impacts of the lockdowns, the government has provided several rounds of cash transfers of steadily increase amounts, with around 20,000 kyat (about $15.50) given to households in September. Our phone survey evidence suggests just under half of all households received these transfers in September – media reports also confirm significant targeting problems – so perfect targeting in the simulations is an unrealistic scenario. Nevertheless, the microsimulation evidence shows that perfectly targeted 20,000 kyat transfers have only a moderate impact on extreme poverty, which falls by 18%—from 31.6% to 25.9%. It takes a 60,000 kyat transfer to halve poverty during a lockdown. Once a lockdown ends, however, the evidence suggests the situation is quite different: Even 20,000 kyat transfers help bring extreme poverty much closer to pre-COVID poverty rates in those circumstances.

What are the implications for social protection in Myanmar during the COVID-19 pandemic?

First, the government and its partners should aim to give larger cash transfers during lockdowns because so many households simply earn zero income when stay-at-home orders are in place, and because more generous transfers might also improve adherence to the restrictions, thus curbing spread of the disease. Second, to limit the fiscal costs of larger transfers, recovery phases could place more emphasis on targeting those still without work, such as through cash-for-work programs that would also help build up much needed community infrastructure. Finally, the government should provide extra protection to nutritionally vulnerable households with pregnant women or young children.

Our research indicates Myanmar is in a dire economic situation that will require dramatic increases in fiscal resources for social protection, more effective and innovative delivery mechanisms, and closer monitoring and evaluation to ensure interventions deliver desired results. Without these urgent steps, Myanmar’s second wave of poverty could well be a tsunami of untold misery.

Derek Headey is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division (PHND) and the Myanmar Agricultural Policy Support Activity (MAPSA) in Yangon. Than Zaw Oo is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division (DSGD) in Yangon; Kristi Mahrt is a DSGD Senior Research Analyst in Yangon; Xinshen Diao is DSGD Deputy Director; Sophie Goudet is a Senior Technical Advisor on Nutrition in Yangon; Isabel Lambrecht is a DSGD Research Fellow in Yangon. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.