This post is part of the FAO-IFPRI initiative on Food Systems and Obesity in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Obesity is increasing worldwide for all subpopulations of age and gender. It is a risk factor for many non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure and constitutes one of the leading risk factors causing early death and disability. Although estimates of obesity rates seem to diverge (see below), they agree that women carry a higher burden than men.

Currently, there are two leading sources of aggregate long-term obesity estimates: Those published by the WHO-NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) and those elaborated by Global Burden of Disease 2015 Obesity Collaborators (GBD Collaborators), coordinated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).

The estimates from these two sources differ in many instances—and some of the discrepancies are large. These differences pose problems for policy makers and for health and nutrition researchers seeking consistent data. Below, we briefly examine the divergent estimates for age-standardized rates and some possible reasons why they arise.

Both teams base their calculations on the aggregation of different population-based nationally and sub-nationally representative studies. NCD-RisC pooled 2416 studies, covering 128.9 million participants aged 5 and older, whereas the GBD Collaborators calculations included 1842 studies, with 68.5 million people over 2 years of age covered. Their estimates differ slightly on the time and country scopes, with WHO reporting data from 1975 to 2016 for 200 countries, whereas GBD does so for the period between 1980 and 2015 for 190 countries.

Prevalence rates of overweight and obesity by age groups, sex, and year are reported in both studies; however, only GBD Collaborators presents estimates on the number of individuals affected by either obesity or overweight. For both, the age categories for adults include individuals 20 years and over. [1] However, WHO-NCD defines children and adolescents as individuals 5 years to 19, while GHDx includes persons 2 to 19 years old in the category.

The definitions of obesity are similar in both studies for adults: A body mass index of 30 or more. However, for non-adults the definitions differ: The NCD-RisC uses as a cut-off values above 2 standard deviations from the median of the WHO growth reference for children and adolescents 5-19 years old (which is based on U.S. data), while the GBD Collaborators uses standards of the International Obesity Task Force to define overweight and obesity among children (which is supposed to be based on a more international benchmark). The fact that the separate definitions of obesity lead to different estimates of prevalence in children and adolescents has been already highlighted in other studies.

The statistical methodologies utilized to expand the sparser collected data so as to cover the countries, population groups, and years considered are also different (see the descriptions in Abarca-Gomez et al, 2017 and GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, 2017).

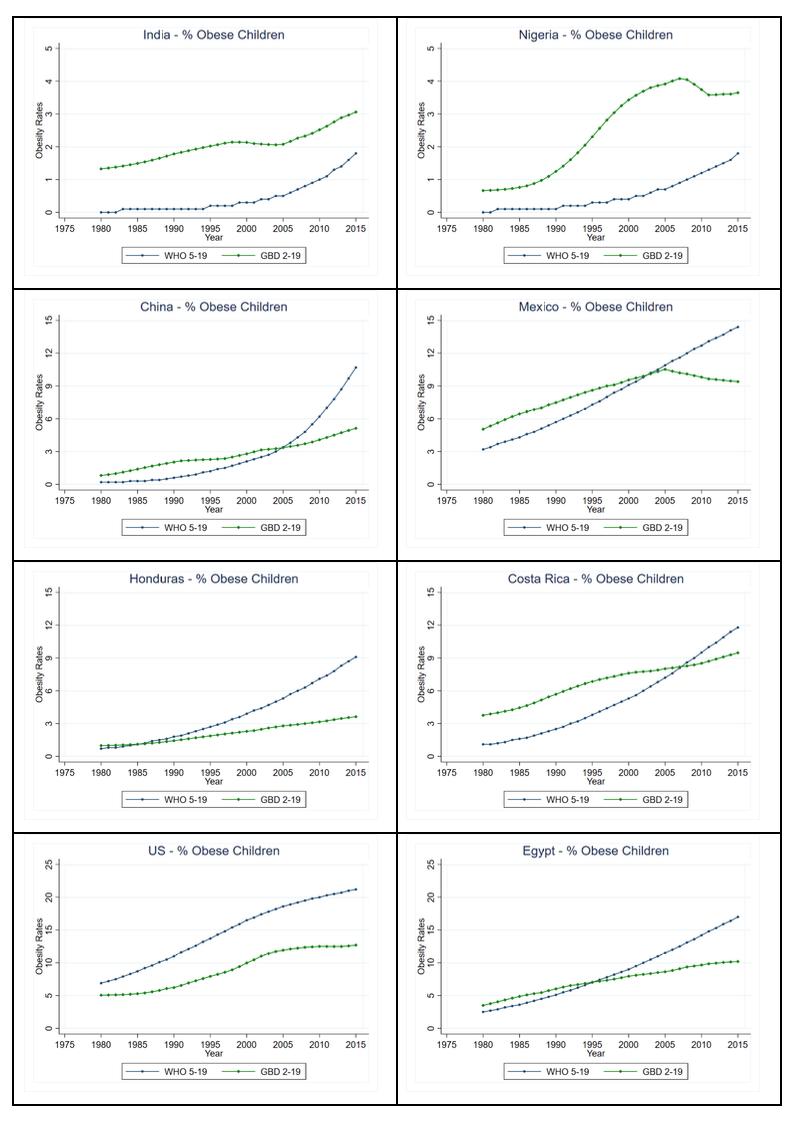

These differences in definitions and methodology play a role in the two groups’ diverging obesity estimates, some of which are summarized in the graphs below, separating adults, and children and adolescents.

In some cases, they follow each other quite closely, such as the case for adult obesity in China and Honduras. But at other times, they report highly different values converging to close estimates, as can be seen for obese adults in Mexico; or with close estimations in the beginning and diverging over time, as in the case of obese adults in Nigeria. In Egypt, GBD Collaborators estimations are consistently over 3 percentage points higher than those for WHO.

Adults

IFPRI

Children and adolescents

In the case of children and adolescents as well, the story they tell is sometimes radically different. This can be seen in the case of childhood obesity for Mexico, where NCD-RisC reports a growing constant trend, whereas GBD Collaborators shows the incidence to stabilize and then decline in recent years. For childhood obesity in the United States, NCD-RisC estimates are almost twice those reported by GBD Collaborators; meanwhile, the opposite is observed for India and Nigeria. For China, Honduras, Costa Rica, and Egypt, although at different scales, GBD Collaborators estimates are higher earlier in time, but lower than WHO at later dates.

IFPRI

Conclusion

Overall, both sources suggest continuous increases of the prevalence of obesity around the world, with the NCD-RisC showing smoother and accelerating obesity rates. However, as shown, there are also visible differences in the shape and evolution of the indicators, which can affect policy decisions depending on which estimates are utilized. Decreasing or tapered prevalence of obesity would require a different set of interventions than a continuously increasing one, for example.

In general, the divergences in estimates seem less pronounced among adults while they appear relatively larger among children and adolescents, even when adjusting for the different scales in the graphics. Of course, a main cause (already highlighted in earlier studies) is the difference in the definitions of obesity on which the estimations were based (others may also be driven by the dissimilar age brackets considered, the econometric methods and the underlying data). In order to be able to understand the complexities of the issue, as well as to design adequate policies, efforts to refine the estimates of the prevalence of obesity worldwide should be strengthened, ideally ensuring that the teams of scientists working on these estimates harmonize their methodologies and produce convergent results.

Eugenio Díaz-Bonilla is Head of IFPRI’s Latin American and Caribbean Program; Florencia Paz is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division.

[1] Although the data published in the WHO website shows a title that says +18 years, the corresponding literature estates that the estimations where done for the cohort 20 years and older. Also, the accompanying data for children and adolescents goes up to 19 years.