How can women’s voices be amplified in a situation of prevailing patriarchal norms? Even more importantly, what should be done so that these voices are not only heard, but also acted upon?

A new issue brief by IFPRI, the IFPRI-led CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM), and the CGIAR GENDER Platform adds important insights into the conversation around these questions. It summarizes evidence from the Civil Society Mapping Project in Mali, where—as in much of Africa—civil society organizations (CSOs) play a critical role in helping citizens organize and pursue shared objectives, often with the goal of holding local authorities accountable. The findings indicate Malian women have high participation rates in nearly all types of CSOs, but suggest they face constraints in translating that participation into political influence.

Why focus on gender?

As in many developing countries, in Mali there is a known gender gap in civic knowledge and participation that more civic leadership by women’s CSOs could help to mitigate. Thus the project team analyzed a full range of active, local-level CSOs, specifically focusing on their gender composition. Women in Mali are often highly organized at the local level—frequently in self-help groups or organizations related to economic activities. However, due in part to that economic focus these groups are often not recognized by outside actors as viable CSOs, despite their strong networks and group infrastructure. By analyzing the full landscape of Malian CSOs and the role of women in them, the project aims to understand how this social capital could be better utilized.

Findings

Overall, 757 respondents (34% female and 66% male) were interviewed as part of the project, covering 58 communes (40 rural and 18 urban). The selected communes span regions in the north, south, and center of the country, including Gao, Kayes, Koulikoro, Mopti, Segou, Sikasso, and Timbuktu. Participants were asked to list up to eight of the most active CSOs currently operating in their commune. Respondents were prompted to consider informal CSOs that may serve the same role as more formal CSOs.

The respondents named a total of 4,893 CSOs—an average of 6.5 CSOs per respondent. As Figure 1 shows, 1,179 of these were women-only CSOs, 738 were men-only, and 2,144 were mixed-gender CSOs (comprising male and female members and led by either gender).

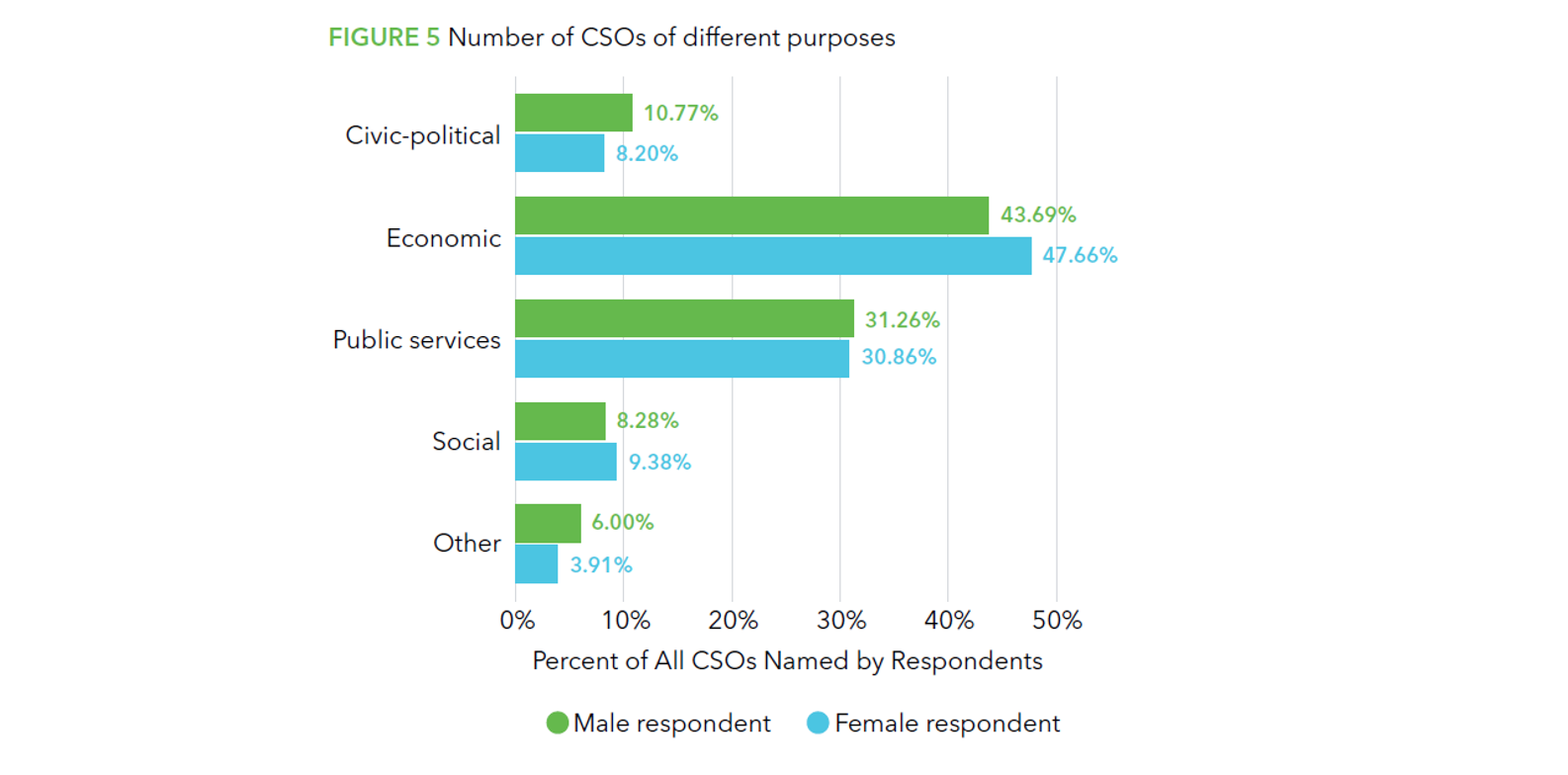

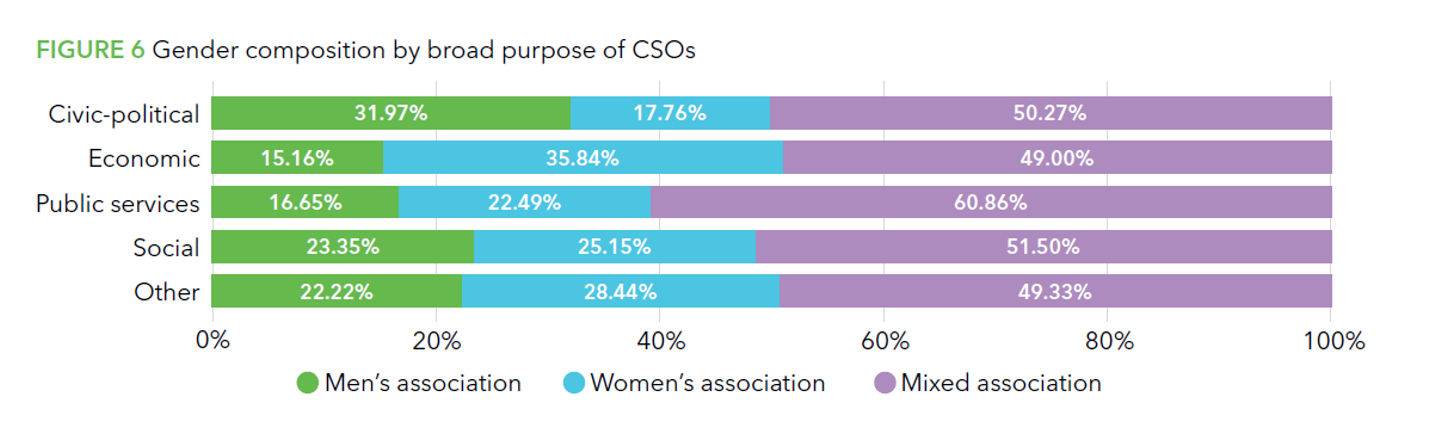

These CSOs serve different purposes: economic, public services, civic-political, social, and other (groupings by the authors based on an open-ended question posed to the respondents). Economic-focused and public service-focused CSOs are by far the most common types.

For each of the five purpose categories, there are more all-female CSOs with that purpose than all-male CSOs, with one significant exception: For civic-political groups, 32% are men’s CSOs, while only 18% are women’s CSOs, and the remaining half are mixed gender CSOs (Figure 6). Women’s groups are less likely to engage in politics, which mirrors other findings pointing to a pervasive gender gap in nearly all forms of political participation.

The authors find strong evidence that women have substantial coordinating capacity and social capital—and this spans groups of all purposes.

Conclusions and policy lessons

These results suggest that lack of social capital or organizing capacity are not likely to be binding constraints on women’s civic participation in Mali. Instead, the biggest constraint appears to be translating women’s group participation into effective civic and political engagement.

Lessons from previous research can inform this challenge. Factors that have led to increased women’s political participation in Africa include the proliferation of women’s movement groups, educational opportunities, economic empowerment, and civil society advocacy. Greater socioeconomic empowerment, measured as mobility outside the village and participation in household decision-making, is correlated with greater political knowledge, political opinions, and support for pro-women policies among rural women.

More research is needed about which strategies for converting women’s organizational capacity into civic and political engagement will work best—and with which groups and environments. Case studies of particularly successful women-led CSOs would be especially useful in revealing what factors give those groups agency and voice. Finally, more work is needed, broadly, on drivers of women’s collective agency—and to develop rigorous methods and tools for measuring it.

Katrina Kosec is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division; Evgeniya Anisimova is Communications Manager for the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM).

This research was funded in part by the CGIAR GENDER Platform; PIM; the Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies and the Office of Research at the University of Notre Dame; and the Scowcroft Institute of International Affairs at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University.