Public works programs have the potential to reduce poverty, provide resilience for workers to economic shocks, and improve infrastructure. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), India’s large national workfare program, has provided 3.07 billion person-days of work at a guaranteed minimum wage in the 2024 fiscal year alone, and received attention for both its scale and its role as a safety net for workers. The program also has significant potential to empower women. It guarantees equal pay for men and women and has a bottom-up participatory planning process in which anyone working in the program can propose the construction of assets that could improve their lives, livelihoods, and resilience to shocks.

Yet as with any program, the success of MGNREGA critically depends on how it is implemented in practice, and whether (and which) individuals can leverage program resources to meet their goals.

A September 28 IFPRI workshop in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, convened by the CGIAR research initiatives on Gender Equality and National Policies and Strategies, explored these issues. The event, “Leveraging the Mahatma Gandhi NREGA for resilient livelihoods for women: New insights, old bottlenecks, innovative solutions,” brought together members of civil society organizations, researchers, and representatives of international donor organizations, financial institutions, and government agencies. They discussed the challenges facing the MGNREGA in Odisha and elsewhere and to highlight potential solutions for improving women’s role in the selection of assets under the program and utilizing these assets to build resilient livelihoods.

The workshop led off with brief presentations of IFPRI’s recent work on the MGNREGA in India. Sudha Narayanan, IFPRI Senior Research Fellow, noted that the pathway from assets to livelihoods is not automatic, and that, while individuals who receive assets rate them as very useful, ensuring that the assets are well-targeted to local value chains and that assets are bundled in ways that make them productive would improve their effectiveness. For example, coconut and cashew plantations perish without bundled irrigation infrastructure, which in turn requires water access to work well.

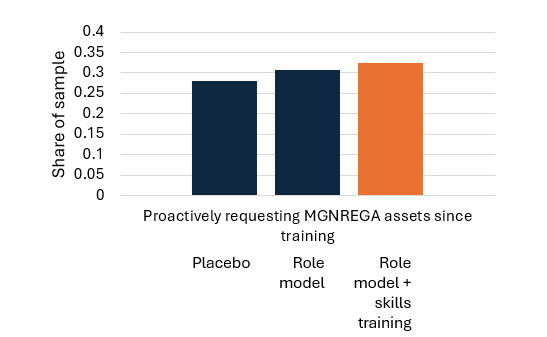

Kalyani Raghunathan, IFPRI Research Fellow, noted that while community-based planning like that done under MGNREGA has many benefits, it can also be influenced by local norms and socioeconomic inequalities, including a tendency to exclude women from decision-making. She presented evidence from a randomized trial showing the effectiveness of information, role model and skills training interventions in enhancing women’s voice within the asset selection process. While a role model intervention on its own did not increase women’s influence over asset selection, when combined with a skills training aimed at boosting women’s aspirations and comfort in public speaking, the study found that women were 16% more likely to request assets (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Effects of role model and skills training at amplifying women’s voice in asset selection

Source: Based on analysis of randomized control trial on the effects of role model and skills training interventions on increasing women’s voice and agency in MGNREGA asset

selection (described in Kosec et al. 2023).

Presentations from Soumyajit Ray, IFPRI Senior Research Analyst, and Sabina Yasmin, LEAD-KREA Research Fellow, emphasized specific barriers women face in participating in MGNREGA asset selection, based on mixed methods research in Odisha and in agrifood policymaking more generally in India—drawing from a recent Women’s Empowerment in Agrifood Governance (WEAGov) pilot study conducted in India. A local graphic artist captured insights from these presentations of evidence from recent IFPRI research and its relevance for leveraging MGNREGA (Figure 2).

Figure 2

In the second part of the workshop, participants discussed how to further strengthen the MGNREGA program so that it can serve as the basis for resilient livelihoods, especially for women. Participants collaborated to write a set of key policy recommendations, which they called the “Bhubaneswar charter” in honor of the workshop location. The group attempted to integrate two broad areas often discussed in isolation: Asset creation under the MGNREGA and training needs and approaches to strengthen rural women’s voice, with the aim of providing actionable inputs.

- Promote bundling of assets: A bundling approach—where several assets are provided together to the same household or beneficiary—leads to higher benefits. We recommend identifying and compiling a list of asset bundles that have positive returns, are associated with a higher likelihood of beneficiaries exiting the MGNREGA program, and minimize the risk of tradeoffs. Some examples include intercropping of horticultural and other crops in fruit tree plantations to ensure short-term returns even as the fruit trees mature or combining farm ponds with water recharge structures and boundary plantations of trees and horticultural crops.

- Improved convergence: Efforts at convergence—that is, enabling coordination between government departments and across programs to improve service delivery—must occur at block, district, and state levels. District administration can play a key role here, as all departments report to the district administrator. Orienting key district officials on the need for convergence could go a long way towards ensuring that this is implemented. At the same time, providing other complementary inputs such as training and credit to the households that receive MGNREGA assets would help them utilize assets to their maximum potential.

- Incorporating flexibility: We should cease associating durability with high cost in asset designs. There are many durable low-cost designs that use locally produced, sustainable materials. Compiling examples of such asset designs from NGOs and other partners could help build a library of options and increase their likelihood of being selected.

- Climate and resilience: MGNREGA assets can help sequester carbon, halt soil erosion, and recharge groundwater—building household resilience against climate shocks. Adapting designs to the specific climate needs of a location, such as altering dimensions or materials based on climate assessments, can make assets themselves resilient. More deliberation is required to identify the climate data that would be needed for this exercise, but a useful starting point could be to put together State Action Plans for Climate Change, District Disaster Management Plans and MGNREGA plans to identify areas of intervention.

- Additional human resources: The Gram Rozgar Sewak, the key village-level MGNREGA functionary who is responsible for raising awareness of, enabling access to and ensuring the smooth implementation of the program, operates under many constraints and often has too much to do. A supportive cadre of village resource persons from Odisha Livelihoods Mission and similar state-led programs elsewhere can strengthen the creation of MGNREGA assets, especially for women. This cadre could also help enable convergence, including supporting households in registering for different programs or informing them about schemes.

- Planning for assets that respond to needs: At present, there is a gap between what people get and what they want. Assets should better reflect the needs of MGNREGA workers, and the constraints and possibilities offered by the local geography. The participatory, bottom-up approach envisioned in the guidelines can help ensure this and thus strengthen the community’s ability to self-govern and make decisions. Like the Rozgar diwas (“Employment Day”), a “Sampati divas” (“Asset Day”) during the MGNREGA planning window starting October 2 each year can help focus attention and highlight the potential of MGNREGA to provide critical assets to support rural livelihoods, including for women.

- The need for training: Village-level Sustainable Development Goal targets and local climate action plans demand more intensive training for village administration and functionaries. Training on GIS mapping is critical to ensure better placement and usability of assets. Training for beneficiaries is also critical, especially for more technical livelihoods activities, or to encourage participation in asset selection by marginalized groups like women. State governments could maintain a directory of trainers across the state for this purpose. With access to the internet and smartphones expanding, digital materials such as videos or voice recordings in local languages and dialects could be productively leveraged, especially to reach women and marginalized groups who often have poor digital skills or low levels of literacy. However, we recommend that in-person training precede digital modules, to build a rapport with trainees.

- Allow for the repair and maintenance of assets: The current provisions allow for repair and maintenance of community but not individual assets. However, for assets to be remunerative over the long-term, one must account for repair and maintenance needs. This can be built into the MGNREGA guidelines but also incorporated into the schemes and policies of the converging line departments, such as the horticulture department or the department of fisheries.

Recommendations around these issues were developed with the specific case of Odisha in mind but are broadly generalizable and can be implemented in many states. As we approach 20 years since MGNREGA was first passed, we hope that the outcomes from this workshop are helpful in ensuring the program’s continued success.

The following people (the Bhubaneshwar consortium) contributed to this blog post: Sudha Narayanan, Kalyani Raghunathan, Katrina Kosec, Jordan Kyle [IFPRI]; Meekha Hannah Paul [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH-India]; Deepak Kumar [Gram Vaani]; Satish B. Agnihotri [Indian Institute of Technology-Bombay]; Indu K. Murthy [Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP)]; Partha Sarathy [Skillgreen]; Aditi Panda [Academy of Management Studies (AMS)]. Other participants came from Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (NIRD&PR), Gram Vikas, Azim Premji Foundation, Leveraging Evidence for Access and Development (LEAD) at KREA University, Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Intellecap, and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).