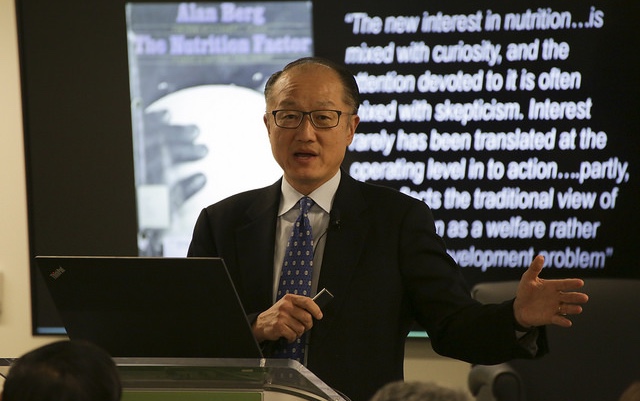

“The goal that we must all embrace is equality of opportunity … you cannot have equality of opportunity if children are not appropriately nourished,” said World Bank Group (WBG) President Jim Yong Kim, delivering the 27th Annual Martin J. Forman Memorial Lecture at IFPRI Dec. 6.

Achieving the SDG targets on nutrition requires a $7 billion investment per year, and the return on investment is substantial—almost a trillion dollars of value added to the global economy, Kim told the audience at the lecture. The event commemorates the impact of its namesake—who headed USAID’s Office of Nutrition for more than 20 years—on international development.

The problem, Kim said, comes in faltering political will to keep up these investments.

New funds created to address ills such as stunting, breastfeeding, anemia, and wasting often fall short, Kim said. “No amount of money, and stated political commitment from donors and good people, will change the picture—unless leaders of all countries take these issues more seriously,” he said.

Countries often back off their commitments when economic circumstances change, he said. For instance, investments in health and education by countries borrowing from the WBG’s International Development Association (IDA) funds typically stop when the loan terms shift from 40 years with 0 percent interest to 30 years, 2 percent interest, he said.

Poor countries, Kim said, also often “game the system,” waiting for donor countries to give money for vaccination programs because of their own fears of vaccine-preventable diseases rather than making their own, proactive investments.

Failing to invest adequately in nutrition has dire global consequences, Kim said. “This is the issue that haunts me: 155 million children under 5 are stunted worldwide; 38 percent of children in Ethiopia and India and 47 percent in Guatemala,” he said. Kim showed a slide displaying an image of the brain of a child with stunting and that of a normal brain: Stunted children can have as much as 40 percent less brain volume.

Stunted children do not learn or earn as well as their well-nourished counterparts, Kim said, a problem that has far-reaching ramifications. In a rapidly digitizing world where, for example, 85 percent of existing jobs in Ethiopia depend on manual labor and could be wiped out by automation, charting a way forward will require a capable, educated workforce.

To focus global attention and resources on such problems, Kim pointed to the WBG’s recently announced Human Capital Project, which will quantify the links between investments in human capital and economic growth, country-by-country.

Human capital accounts for about 65 percent of the overall wealth in high-income countries, Kim explained, but that number declines drastically for countries lower on the income scale, averaging only 40 percent. This divide has clear economic impacts. Over the past 25 years, Kim said, the average difference between the top quartile of countries investing in human capital and bottom quartile was 1.25 percent of GDP per year.

“What if people who are upset about the quality of human capital started blocking the streets?” Kim asked.

One aim of the Human Capital Project’s country rankings is to provoke action by governments. The results are likely to create unpleasant surprises when some countries find themselves ranked below others that they have historically considered themselves superior to, Kim said. When that happens, opposition parties will take note and heads of state and finance ministers will have to focus.

“If we are committed to ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity, we have to use every single tool we have on behalf of the poor and not to hurt anyone else,” Kim said.

Katarlah Taylor is a Senior Events Specialist at IFPRI.