Despite some improvements during April and May, the Gaza Strip continues to face catastrophic food insecurity with a high risk of famine, according to the latest assessment of the Famine Review Committee of the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC), released on June 25.

The IPC reports that 96% of Gaza’s population of 2.2 million people face high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 4) through September, while 22%, over 495,000 people, face catastrophic levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 5).

During much of April and May, food assistance inflows into Gaza increased over previous low, irregular levels. This effectively averted the IPC’s worst-case scenario of last March, which projected a majority of Gaza’s population could face famine by May-July.

Before the start of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, 2023, over 10,000 trucks with food, fuel, and other products were entering Gaza every month (500 per working day). After the war began, Israel severely restricted border crossings, and its continuing attacks in Gaza further disrupted supply routes and routines. In April, however, supplies significantly recovered. Nearly 6,000 humanitarian and commercial truckloads were allowed into the Gaza Strip, many including food assistance (Figure 1). This recovery lasted until early May, when humanitarian assistance fell to less than 3,000 truckloads for the month following Israeli attacks on Rafah in southern Gaza and the renewed closure of southern border crossings. By June, truckloads entering Gaza had fallen to only 80 per day, a fraction of pre-war numbers.

Figure 1

The temporary recovery in food aid did help improve child nutrition and stave off a major famine, according to the new IPC assessment. However, across all dimensions of food security (availability, access, stability, and utilization), the situation remains extremely fragile and volatile.

Availability

Gaza’s population has become almost entirely dependent on food aid. As a result of the conflict, local food production and distribution systems have either collapsed completely or are just marginally surviving through informal market channels. As noted in a previous blog post, much of Gaza’s agriculture land, orchards, greenhouses, and irrigation infrastructure have suffered extensive damage. According to UNOSAT’s latest assessment, the share of damaged agriculture land increased from 13% to 57% between November 2023 and May 2024. Furthermore, about 70% of livestock has been lost, and fishing production has been largely halted due to extensive damage to boats, lack of fuel, and unsafe conditions to access fishing boats.

Access

Access to purchased foods remains severely limited throughout Gaza, not only because of disrupted domestic markets and distribution systems but also because of rampant inflation. The prices of salt, wheat flower, sugar, vegetable oils, and fresh food rose sharply in the first quarter of 2024, although they fell somewhat in April and May as a result of larger flows of food assistance. Prices also remain highly volatile, showing strong correlation with fluctuations in the amount of food assistance being allowed into Gaza. According to Palestine Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), prices of some staple foods decreased in April (Figure 2) only to increase again in the second half May (though they are below the peak levels reach in February 2024, when the number of trucks with food assistance entering the Gaza Strip was at its lowest).

Figure 2

Stability

Food price volatility is affecting cash-based assistance programs, as are limited electricity supplies and internet connectivity to mobile financial services. Access to cash is also a problem because of liquidity shortages with local banks and ATMs, and remittances have dropped at the same time. As a result, Gaza’s population is becoming almost entirely reliant on in-kind food assistance.

According to the IPC assessment, in April, 82% of the population in the governorate of Rafah received food assistance. This share was about 75% in Deir al-Balah and Khan Younis and almost 60% in North Gaza. In North Gaza, access to humanitarian food assistance improved during May to reach 80% of the population, while access in the other parts of the territory, where conflict was centered, fell starkly—notably to only 25% in Rafah by June. In Deir al-Balah and Khan Younis, only about 60% of respondents declared having received assistance in May, compared with 75% in April.

Utilization

Effective food “utilization” continues to be highly constrained, in part by the extreme shortage of clean drinking water and energy, and, hence, difficulties cooking and preparing meals safely and hygienically. The lack of basic sanitation and hygienic conditions in most areas where the mostly displaced population of Gaza lives is further increasing the risk of gastrointestinal and other disease and limiting people’s absorption of nutrients. Gaza’s extremely high population density has put further pressure on limited water and hygiene supplies, increasing the risk of disease outbreaks, epidemics, and other catastrophic health outcomes.

Continuing risk of famine

These food security conditions are, clearly, highly unstable, driven by the changing intensity of the conflict and the volatility in access to humanitarian assistance. Accordingly, while food security outcomes improved during April and parts of May, the most recent data suggest a renewed deterioration from late May and early June.

Figure 3 shows the broad trend: Gaza’s food security crisis was worsening across all regions through early 2024, show modest improvements in March, and then more dramatic ones in April and May. But since then, with aid deliveries hitting renewed obstacles, the crisis has worsened again, with a considerable portion of the population still experiencing crisis level or worse food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or higher) across all three regions. It should be noted that in the current volatile and precarious food situation, temporary improvements can quickly be offset by persistent, recurring challenges in food availability and distribution.

Figure 3: Trends in Households Hunger Score from November 2023 to June 2, 2024 by governorate

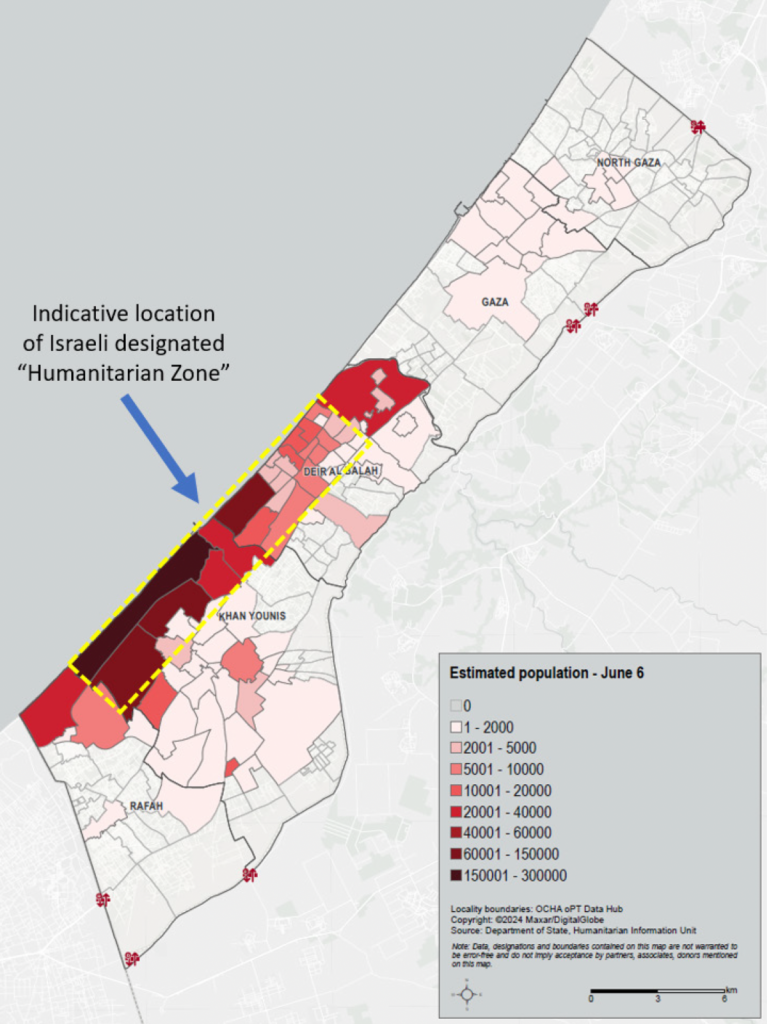

The risk of famine is exacerbated by the displacement of the majority of Gaza’s population to the essentially unlivable areas of the so-called “humanitarian zones” designated by Israel. These lie in the coastal areas of Deir al-Balah and Khan Younis, where hundreds of thousands of people are concentrated in very small areas in makeshift camps. In some areas, there are well over 150,000 people persquare kilometer (Figure 4). These areas also lack most basic services, including clean water supplies and basic sanitation points, which is enhancing the risk of disease and raising the risk the situation will rapidly deteriorate into an even broader humanitarian catastrophe.

Figure 4: Estimated population density in makeshift sites in South and Central Gaza, June 6, 2024

(People per square kilometer)

While the improvements in food assistance delivery in April and May were encouraging, the highly volatile nature of the crisis in Gaza means we in the international community cannot let down our guard. As the latest IPC assessment shows, famine and epidemic remain an extremely real threat for wide swathes of the Gazan population. This precarious situation again emphasizes the need for an immediate, lasting ceasefire and for coordinated humanitarian aid to provide the critically needed food, water, fuel, medicines, and sanitation and hygiene supplies.

As highlighted in a related publication, these rapidly changing conditions urgently require continuous real-time monitoring of food crisis and famine risks—this includes integrating field and remote sensing data and ensuring transparent access to satellite imagery for identifying damages to livelihoods (including to food production and distribution infrastructure, as well as basic services), intensity and extension of hostilities, population displacements, tracing of humanitarian transports, availability and quality of food assistance and other factors determining food access, such as food prices.

Rob Vos is Director of IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Sara Gustafson is an IFPRI consultant; Sediqa Zaki is an MTI Research Analyst; Brendan Rice is an MTI Research Specialist. Opinions are the authors'.