The Reach, Benefit, Empower framework—a tool for clarifying gender strategies for development projects—emerged in 2016 following a review of a group of agricultural development projects under the Gender, Agriculture, and Assets Project Phase Two (GAAP2) portfolio. Even though the stated aim of all the projects was to empower women, closer examination found very little that would contribute to that goal—understood as the ability to make strategic life choices. Instead, most projects focused on reaching women—for example, with training. It wasn’t even clear if they were benefiting women, by providing them with something they valued, let alone contributing to their empowerment.

The insights from that initial review, seeking to explain what about the goal of “empowerment” was different from the goals of typical programming—even specifically gender-responsive programming—shaped the Reach, Benefit, Empower framework. It has proven very useful in helping researchers and managers refine their thinking and carry women’s empowerment goals through from ambition to programming, implementation, then evaluation.

Now, we have moved a step further—adding “Transform” to what is now the Reach, Benefit, Empower, Transform (RBET) framework. The aim is to prompt users to think about the deeper levels of structural or normative changes needed to make systems more equitable. As we observe the 2024 International Day of Rural Women (October 15), we believe the RBET framework can be a powerful tool for advancing equity and empowerment for women.

Drawing on earlier work showing how RBET can contribute to women’s empowerment and gender parity, we applied the framework to efforts to strengthen women’s rights to natural resources—outlined in a new brief, From Reach to Transformation: Leveraging the RBET Framework to Secure Women’s Land & Resource Rights.

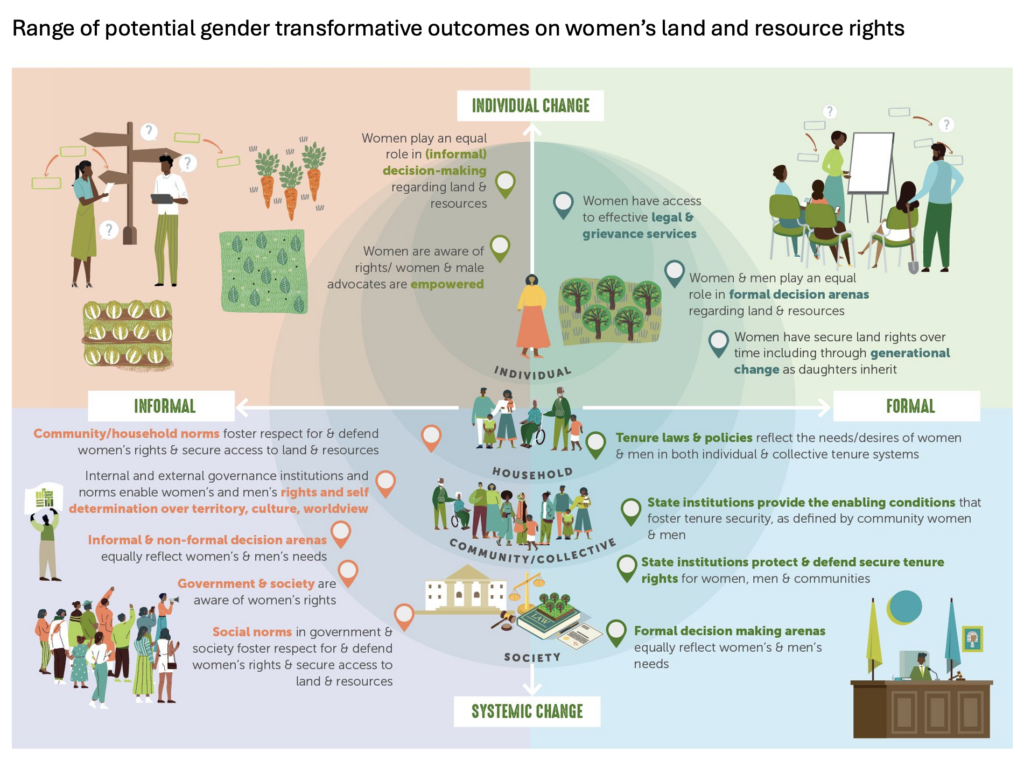

Our assessment focused on projects within the global initiative on Securing Women’s Resource Rights Through Gender Transformative Approaches. We found the Gender@work framework helpful. It uses two scales (informal to formal and individual to systemic), creating four quadrants in which to consider what transformative changes are needed to foster equitable resource rights for women.

The RBET framework, then, prompts thinking about the kinds of goals, activities and indicators that would constitute each element of “reach, benefit, empower, and transform” for women’s resource rights in each of the four quadrants (Figure 1 and summarized below):

Figure 1

- Formal-systemic issues such as state recognition of women’s land rights and security of women’s land rights

- Formal-individual issues such as women’s decision-making and individual security of women’s land rights

- Informal-individual issues such as women in decision-making and women’s knowledge of land rights

- Informal-systemic issues such as security of women’s land rights and women in decision making

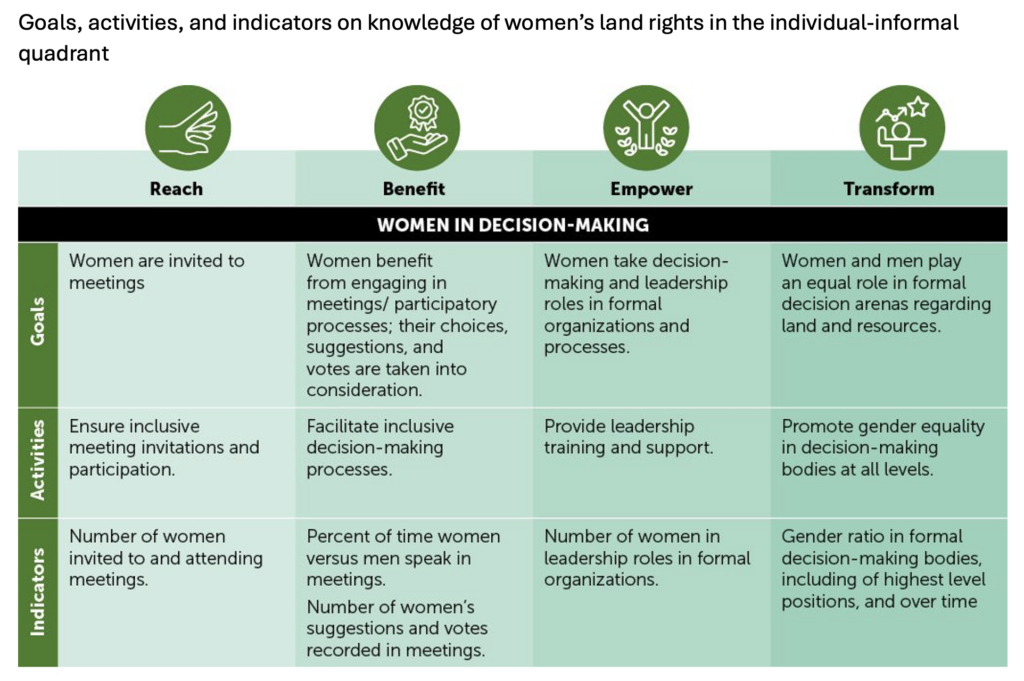

Even though some topics can be placed in more than one quadrant, the way these play out, and the way we would measure change, differ for each. The brief provides examples of what this might look like, along with sample interventions and indicators for different topics. For example, knowledge of women’s land rights is a major component of the Informal-Individual quadrant, but what that entails changes as you move from reach to transform (Table 1).

Table 1

In drafting the brief and identifying indicators for each quadrant and level of change, it became clear that it’s much easier to identify “reach” indicators, such as number of people trained, and much harder to measure benefits (such as from a training) or empowerment. However, tools such as the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) or the Women’s Empowerment Metric for National Statistical System (WEMNS) have made the latter challenge easier. These provide indicators that can be applied to specific aspects of women’s land rights; WEMNS even has a full module on rights and security of tenure for land and dwellings.

Transformation, we found, is even harder to measure because it’s a systemic change, not an individual one. To assess it, qualitative indicators tailored to each context may be more appropriate, in many cases, than standardized, quantitative indicators.

Our brief therefore does not provide definitive strategies or indicators for empowering or transformative approaches. Rather, it is intended to stimulate conversations within each project or context about what kinds of interventions go beyond “reaching” women, and how we would know if those interventions are successful. These conversations—which should be held with the women seeking change—are an important starting point toward transformative approaches that strengthen women’s land and resource rights.

Ruth Meinzen-Dick is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Natural Resources and Resilience Unit; Anne M. Larson is Principal Scientist and Team Leader: Governance, Equity & Wellbeing with the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF). This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

This work was supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) through the Women’s Resource Rights grant (https://www.cifor-icraf.org/wlr).