In 186 countries worldwide, cash transfer programs are the cornerstone of social protection, outnumbering social security or pension plans. These offer critical financial lifelines to vulnerable households, aiming to alleviate poverty by providing steady cash support. However, these programs can become long-term fiscal burdens for governments due to limited turnover of recipients, particularly when the programs do not lead to lasting reductions in poverty.

To address this problem, economic inclusion programs (including so-called “poverty graduation” programs) are increasingly being introduced as complementary or alternative approaches. Economic inclusion programs aim to provide a cohesive set of mutually reinforcing interventions to help individuals sustainably move out of poverty. Governments are also increasingly interested in seeing if these programs can “graduate” households from relying on cash transfers.

Economic inclusion programs typically provide one-time asset transfers, financial inclusion interventions, skills training, and consumption support for a set period. Evidence suggests that they can be more effective than cash alone in empowering recipients to achieve sustainable income gains, potentially offering a viable path toward financial independence (Banerjee et al. 2015, Bandiera et al. 2017). Building on such findings, economic inclusion programs have gained traction, being piloted or implemented in more than 88 countries (Arévalo-Sánchez et al. 2024), with governments actively exploring ways to incorporate these strategies into their existing social protection frameworks.

Egypt’s experience is a case in point. The country’s Takaful cash transfer program has been a vital source of support for millions, but fiscal space is too limited for cash transfers to serve as a solution to poverty (Breisinger, et al. 2023). The hope is that graduating current cash transfer beneficiaries will free up public resources to reach other impoverished households. To garner support for the new option, the government provided cash transfer recipient households with a choice: Would you rather remain eligible for the monthly cash transfer or opt into the economic inclusion program?

In this post, we share evidence from a household survey during the period of recruitment for the economic inclusion program to capture respondent beliefs about their decision. We show that beliefs about the duration of consumption support and the income-earning potential of the program can influence household preferences for the new program. As the number of these programs continues to grow worldwide, such results highlight the importance of designing and communicating compelling economic incentives to encourage take-up of social protection programs by those expected to benefit.

This research is among a number of IFPRI projects contributing to evidence on the effectiveness of economic inclusion programs in Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and elsewhere.

Egypt’s pioneering approach: Allowing choice in social protection

Egypt’s government is innovating within its social safety net by piloting a new economic inclusion approach designed to support beneficiaries’ exit from its cash transfer program. The new economic inclusion program is called “Forsa”—“opportunity” in Arabic. Participants receive productive assets, primarily sheep and goats, short-term consumption support, and relevant training to ensure they can effectively utilize these resources and achieve sustainable income growth. The program is available to current beneficiaries of the Takaful program, as well as to those nearly eligible for cash transfers. Interestingly, the government devised a novel approach to identify economic inclusion beneficiaries who could achieve self-sufficiency: It gave households the option to either remain eligible for the existing cash transfer program or opt into the new economic inclusion program.

Household preferences: Survey during recruitment into the economic inclusion program

The IFPRI evaluation of the pilot program focused on 160 sub-villages across eight governorates. To study how beneficiaries were responding to this choice between cash transfers and economic inclusion, IFPRI researchers conducted a household survey during the economic inclusion program’s recruitment phase. This survey collected demographic data and gauged early adopters’ beliefs about the economic inclusion program.

The results were revealing. Only about 32% of households reported having signed up for the economic inclusion program midway through program recruitment, far below policymaker expectations. Notably, sign-ups tended to come from larger households, those more likely to nominate women as beneficiaries, and households that had experienced recent economic shocks. This suggests that certain household characteristics may make the economic inclusion program more attractive, especially when households face economic instability or need greater support.

Further, respondents had wide-ranging and uncertain perceptions regarding two key design features of the economic inclusion program. First, many were unsure about the duration of consumption support—that is, how long cash transfers would continue on the economic inclusion program. Second, respondents had disparate beliefs about how much monthly income they could earn from the asset provided by the program. Indeed, respondents reported a very wide distribution of beliefs about these topics.

Testing the role of program design: Insights from a video messaging experiment

To understand how perceptions of these program design features affected interest, the survey included an innovative messaging experiment that showed respondents an official video produced by the Government of Egypt’s Ministry of Social Solidarity. Participants were randomly shown one of three different videos. The control group saw a video containing only basic information that had been previously disseminated across communities. In addition, a Transfer Duration treatment showed the announcement of a new official policy on the duration of transfers for consumption support within the economic inclusion program, and a Testimonies treatment shared real Forsa participants’ testimonies about monthly incomes earned through the program. After viewing the video, respondents were asked about their willingness to recommend the program to a friend or neighbor (as a measure of their interest in the program), and about their perceptions of program design.

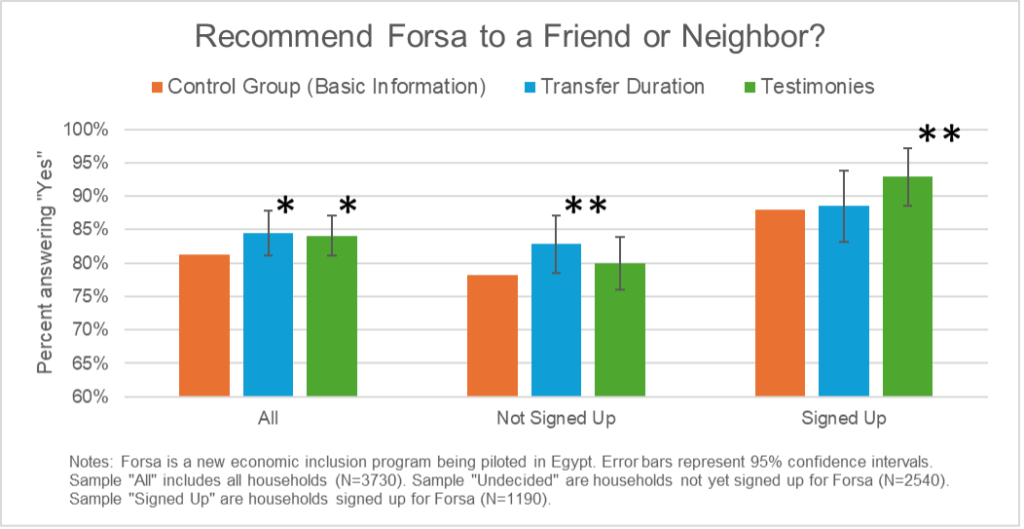

The messaging experiment showed that clarity in communications about these program design features significantly affects interest. Both the official policy announcement on the duration of consumption support and the participant testimonies had a positive effect on the respondent’s willingness to recommend the program to a friend or neighbor compared to the control video showing basic information. In particular, the Transfer Duration video increased interest among those who had not yet signed up for the economic inclusion program, while the Testimonies video increased interest among those who had already signed up (Figure 1).

Figure 1

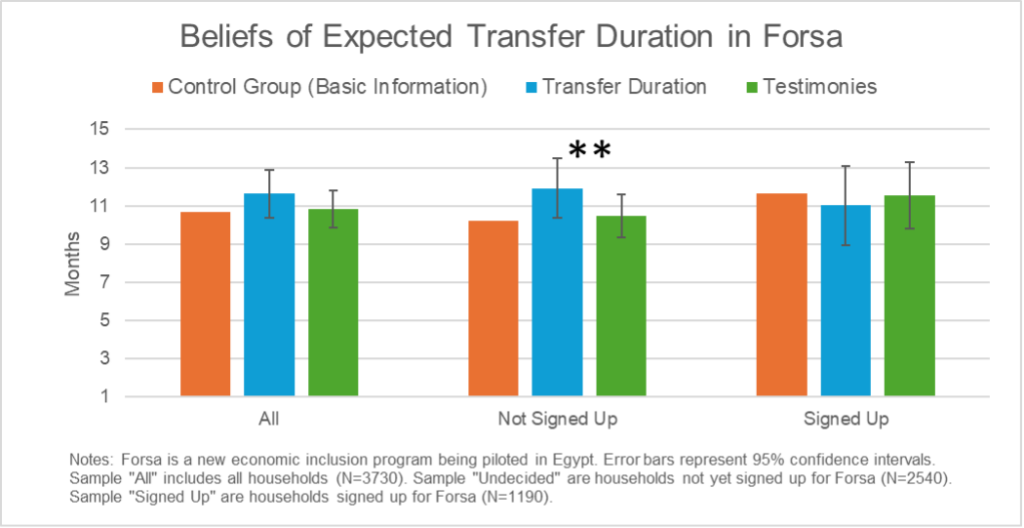

We see a similar pattern when looking at the video’s effects on perceptions of these key design features. Among households that had not signed up, the policy announcement increased perceptions of Transfer Duration , making the program more appealing (Figure 2).

Figure 2

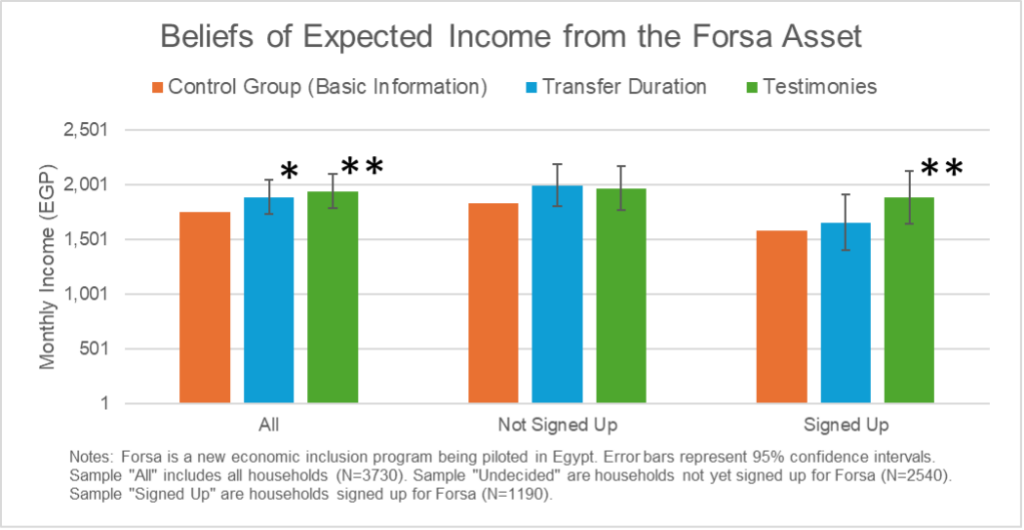

And for those already enrolled, hearing real-life Testimonies about income potential from the program’s assets further increased beliefs about its income-earning potential and enthusiasm for the program, underscoring the importance of credible information and tangible success stories in promoting program uptake (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Implications for policymakers: Designing and communicating effective social protection programs

Altogether, the analysis provides strong empirical evidence that transfer duration and expected monthly income in an economic inclusion program are important design features that may influence participation, particularly when it is competing with an existing cash transfer program.

For policymakers, these findings offer several lessons:

- Program design is crucial. Clear and attractive design parameters, such as the length of time recipients can receive cash support or the income potential from program assets, are key to encouraging transitions to economic inclusion programs. Therefore, policymakers need to decide on these design parameters early on and communicate them consistently to eligible households. Participants must also know upfront whether they would ever be allowed to reapply for the cash transfer program.

- Messaging matters. When recipients are uncertain about program details, they may hesitate to leave a familiar cash transfer system, even if the new program could offer more benefits. However, as the messaging experiment showed, providing clear, targeted communications around program features can significantly influence recipient preferences. For governments seeking to implement economic inclusion programs, clear communication can drive higher participation and improve program outcomes.

- Other factors play a role. IFPRI researchers also matched household responses to a theoretical model to estimate its predictive power. This exercise showed that, in addition to program design, there was suggestive evidence that effort costs, risk preferences, and other factors may influence household choice between cash transfers and economic inclusion programs. So while program design is important, policymakers must bear in mind that these other factors play an important role as well.

The road ahead: Building sustainable social protection systems

As economic inclusion programs gain popularity worldwide, especially in low- and middle-income countries, insights from Egypt’s pilot could inform other nations’ strategies. Combining cash transfers with structured pathways to financial independence offers a promising avenue for reducing poverty sustainably. However, the success of these programs depends on convincing cash transfer recipients to choose a transition to new economic inclusion programs. For policymakers and development practitioners, this means designing programs with clear benefits, transparent structures, and effective communication strategies. As countries explore sustainable approaches to poverty reduction, integrating these insights into national policies could be a step toward more resilient and empowered communities.

To learn more, read our IFPRI MENA Working Paper.

James Allen IV is an Associate Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender, and Inclusion (PGI) Unit; Daniel Gilligan is Director of PGI; Sikandra Kurdi is a Research Fellow and Country Program Leader for Egypt with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit; Basma Yassa is a DSG Research Associate based in Cairo. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

This research was funded by USAID under the “Evaluating Impact and Building Capacity” (EIBC) project implemented by IFPRI, through the World Bank by the United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the CGIAR Initiative on National Policies and Strategies, and the CGIAR Initiative on Gender Equality (HER+).

Referenced Working Paper:

Allen IV, James; Gilligan, Daniel O.; Kurdi, Sikandra; and Yassa, Basma. 2024. Would you rather? Household choice between cash transfers or an economic inclusion program. MENA Working Paper 44. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/158340