By Eugenio Díaz-Bonilla and Jonathan Hepburn

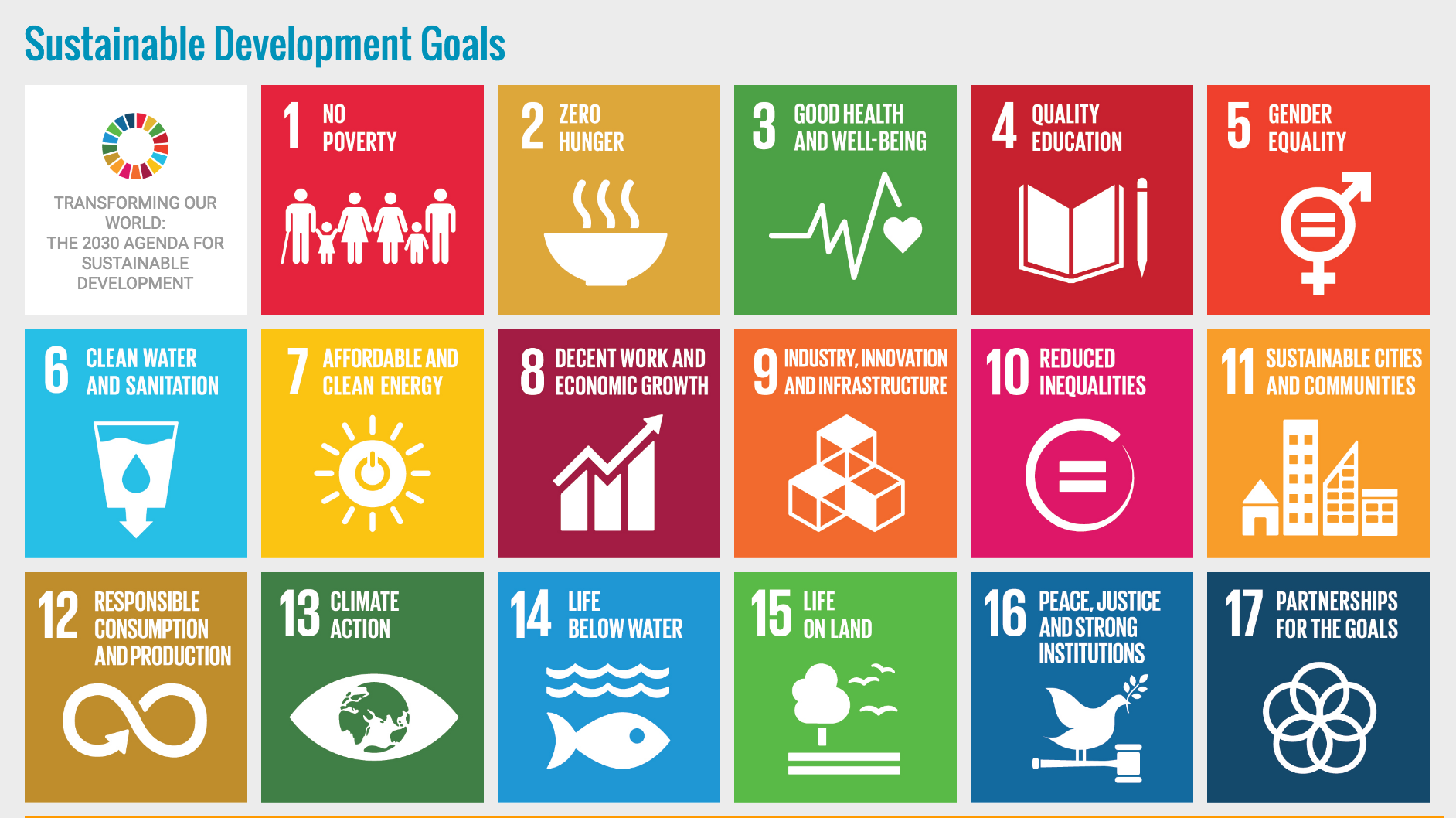

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, approved last year in New York, sets a ground-breaking new commitment for all countries: to end hunger and “all forms of malnutrition” by 2030. This post examines how policies affecting trade and markets are relevant to the new commitments on hunger and malnutrition; looks at past progress and projected trends; and examines options for government action in years ahead.

What do the SDGs say about food security and sustainable agriculture?

Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) commits governments to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.”1 Five specific targets with deadlines also complement this goal.2

The first two targets refer to hunger and malnutrition. In SDG 2.1, governments pledge to “end hunger and ensure access by all people … to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round” by 2030. In SDG 2.2, they add that they will aim “to end all forms of malnutrition,” also by 2030—as well as to reach internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years old, and address “the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons.”

Under SDG 2, governments also agreed to three targets linked to support for small-scale food producers and vulnerable groups. In SDG 2.3, they state their aim of doubling “the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers … including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment.” In SDG 2.4, governments promise to ensure the sustainability and resilience of food production systems, while in SDG 2.5 they commit to maintain genetic diversity and promote equitable access to it.

The signatories to the SDGs also agreed three “means of implementation” targets under SDG 2, specifying actions to help achieve the objectives in this area. SDG 2.a addresses the need to “increase investment … in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development, and plant and livestock gene banks.” SDG 2.b addresses trade explicitly, committing governments to “correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets,” while referring to the mandate of the WTO’s Doha Development Round. Finally, SDG 2.c states that governments will “adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets.”

To achieve the 2030 Agenda goals, governments will therefore need to focus on all three aspects of the “triple burden of malnutrition”: undernourishment, the traditional focus of efforts to fight hunger; micronutrient deficiencies, or “hidden hunger”; and over-nutrition, which leads to problems such as obesity and diabetes.

Finally, commitments under other goals might also require governments to pursue policies and rules affecting trade and markets in ways that have significant consequences for food and nutrition security. While all of the goals are arguably relevant, some might be especially important—such as those on poverty, education, gender, energy, employment, and inequality.

And what do the SDGs say about trade?

The 2030 Agenda makes clear that trade is a means to achieve broader objectives, rather than an end in itself. It adopts a positive view of international trade, while also calling for governments to take action to improve the functioning of global markets.

In particular, SDG 17.20 commits countries to “promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organization.” The declaration also refers to the importance of concluding negotiations under the Doha Development Agenda—although at the WTO’s Nairobi ministerial conference, three months later, members acknowledged that there was no consensus on whether to reaffirm the Doha mandate.

However, the Nairobi ministerial did put in place a framework to eliminate agricultural export subsidies, along with disciplines on measures seen as having similar effects —one of the commitments governments had made under SDG 2.b. Other more significant types of trade distortions, such as domestic support for farm goods, nonetheless remain to be fully addressed by international rules.

Trade policy and rules can help governments to achieve 2030 Agenda targets, such as the commitments in SDG 2.3 on doubling agricultural productivity and incomes for small producers, by improving access to markets, fostering opportunities for value addition, and creating rural jobs. However, while the new goals say explicitly that tackling trade restrictions and distortions in global agricultural markets could help, actions to implement the new commitments that affect non-agricultural markets could be just as important for food and nutrition security.

For example, governments will need to address trade policy challenges in the fisheries sector (an issue addressed under SDG 14), as well as distortions affecting markets for farm inputs, such as fertilizers, seeds, farm equipment, and energy. In addition, they will also need to address services such as credit markets, agricultural insurance, transport, and logistics; and also consider trade policies affecting employment markets in both rural and urban areas, such as those affecting trade in manufactured goods.

Other SDG commitments could also affect trade and markets in ways that have consequences for achieving SDG 2—such as those on intellectual property, “aid for trade,” fossil fuel subsidy reform, fisheries, and least-developed countries (LDCs).

Will progress in improving nutrition continue?

Governments have made rapid if uneven progress in fighting global hunger, with over 200 million fewer people undernourished in recent years. However, recent success in reducing micronutrient deficiency has still been too slow to end malnutrition by 2030, while overweight and obesity has worsened.

Reductions in undernourishment have been driven primarily by progress in Asia, and especially in China. On the other hand, in Africa, there are now almost a quarter more undernourished people than in the early 1990s—despite a drop in the overall share of undernourished people.

Estimates from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) show that, globally, almost 800 million people are still undernourished, of whom 98 percent live in developing countries, mainly in Asia (512 million) and Africa (230 million).

Meanwhile, indicators of micronutrient deficiency remain high—such as the prevalence of anemia in women and children under five. Although this indicator suggests that percentages have declined in the last two decades, progress is still too slow if governments are to achieve the target of eliminating all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

Finally, data on the prevalence of obesity and overweight among adults suggests no decline in any of more than 190 countries with data. An increase in demand for “convenience” in food consumption in particular has led to the expansion of fast foods and highly processed products, which appear correlated with health problems associated with over-nutrition and non-communicable diseases.

How are food and agriculture markets changing?

Better functioning food and agriculture markets will be critical in ensuring that governments can achieve the new commitments, especially as undernourishment disproportionately affects rural populations in low-income countries. Small farms are still estimated to be home to half the world’s hungry, suggesting that agriculture and rural development remain key to achieving the SDGs.

Many developing countries are increasingly relying on food imports to meet growing demand as urban populations grow and average incomes rise. While much of this increased trade is between developing countries, LDC exports have grown far more slowly.

However, food imports represent a declining share of total merchandise exports in developing countries as a group, as well as in LDCs. The trend suggests that, overall, the food import bill has become more affordable for these countries as a group.

At the same time, agriculture and trade policies have also changed in recent decades. Some developed countries that previously provided heavy subsidies to their farm sectors have now reduced the support they provide, or have switched to less distorting forms.

Meanwhile, several large developing countries, some of which historically taxed agriculture, have moved towards providing increased domestic support for the sector. Levels of agricultural investment in many of the poorer developing countries nonetheless remain low, with public goods provision often lagging behind governments’ stated objectives.

Tariffs on farm goods have also fallen in all world regions as a result of unilateral liberalization and due to the impact of preferential trade deals. Tariffs and other non-tariff barriers nonetheless remain significant on a number of “sensitive” farm goods such as beef, dairy, rice, and sugar.

As regards fisheries, while about 40 percent of fishery and aquaculture products are traded internationally, production and trade are adversely affected by illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, as well as harmful subsidies.

Under “business as usual” conditions, the FAO and OECD estimate that the number of undernourished people will fall by about 20 percent in the coming decade. However, this would still leave more than 600 million people undernourished, of which about 220 million are projected to be in sub-Saharan Africa. The projections imply that governments will need to change current policies in order to reach the zero hunger target by 2030—alongside action on nutrition deficiencies, and on overweight and obesity.

Although food prices have fallen from unusually high peaks in recent years, many poor countries arguably remain vulnerable to sudden market shocks, in particular if, as the evidence suggests, climate-related extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense.

Analysis from the OECD and FAO suggests that in the medium term, both production and consumption are due to grow. However, Africa’s consumption of rice, wheat, vegetable oils, and sugar is expected to grow much faster than production, while Latin America is expected to continue producing more oilseeds, meat, fruit, and vegetables than the region is set to consume.

While governments in many developing country regions have significant scope to take actions that would boost farm productivity sustainably, increased trade can also be expected to become more important to ensure that countries can meet growing demand in the future.

What can governments do next?

Both national policies and global rules affecting trade and markets will be relevant as policymakers set their minds to achieving the SDGs. However, governments will need to move quickly in order to ensure that the challenge can be met in time.

Governments can already take action under existing global rules on trade to boost farm productivity and raise incomes in rural areas. Investments in “public goods” such as pest and disease control, research, basic infrastructure, land titling, or farm advisory services are allowed without limits under current WTO rules.

In other areas, such as agricultural domestic support, fisheries subsidies, or access to markets for farm goods, governments will need to start now to negotiate meaningful international disciplines. Trade policy reforms aimed at improving employment opportunities and raising incomes could usefully be targeted at food insecure population groups. Advance planning and additional international resources will also be needed if governments are to collaborate across borders to finance expanded food aid provision to poor consumers, and, in general, poverty-based safety nets, so as to improve economic access to food without adversely affecting how markets function.

Effective trade policy measures to mitigate volatility in global markets are also likely to become more important in the future – such as better global rules on export restrictions, to prevent price spikes from harming consumers in poor food-importing countries.

At the same time, the ambition of the 2030 Agenda can only be realized if governments determine not to shy away from difficult questions, such as correcting and preventing trade distortions in the area of agricultural domestic support. At the WTO, many negotiators have identified this issue as a potential deliverable for the organization’s upcoming ministerial conference in 2017, despite historical difficulties in making progress in this area.

While policymakers may feel daunted by the scale of the task ahead, recent steps forward on agricultural export subsidies suggest that incremental progress is feasible and realistic. Government officials now have an opportunity to take concrete measures towards ensuring that more equitable and sustainable markets actually contribute to the goals of ending hunger and malnutrition.

Eugenio Díaz-Bonilla is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Markets, Trade and Institutions Division. Jonathan Hepburn is Programme Manager, Agriculture at the International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development (ICTSD).

This post originally appeared on the ICTSD site. It is based on a longer ICTSD paper.

1. At the 1996 World Food Summit, governments declared that “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

2. The targets can be seen as giving effect to the progressive realization of the right to food, as well as building on and going beyond other objectives that governments have collectively set themselves, such as the Millennium Development Goals and the targets agreed at the 1996 World Food Summit.