India’s domestic sugar market is in the doldrums, as the international market price of sugar has been falling. With general elections coming up in 2019, managing sugar markets and balancing the interests of sugar millers and sugarcane producers is a serious policy challenge for India’s government. Higher sugarcane production in the 2017-18 crop year has only made the problem more complex. As with many so-called political commodities, the fate of the current government may depend on how it handles this policy issue—particularly given the distressing trend of rising numbers of sugarcane farmers committing suicide due to difficult economic conditions. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, a total of $1.8 billion remained unpaid to sugarcane farmers as of mid-May.

The government has implemented a number of policy fixes to help sugar mills and cane producers. They fall into two broad categories: Increasing exports and finding alternative markets. However, both options are complex, as increasing sugar exports is not easy when world prices are sluggish. Diverting a significant portion of current sugar stocks to the production of renewable fuels, mainly ethanol, also has its own challenges, including government restrictions on food-based feedstock use on energy production.

In addition, per capita sugar consumption is stable or slightly declining globally, and other technologically advanced major sugar producing countries, including Brazil and Thailand, are formidable competitors, so Indian sugar exporters would face serious challenges in the world market.

Growing sugarcane as a commercial crop venture could be an effective tool for reaching the government goal of doubling farmer income by 2022. But bold policy alternatives are needed to make that a reality. This post aims to shed light on the consequences of the removal of restriction on direct sugar use as feedstock for ethanol production on overall domestic sugar demand.

Fall in prices

According to the World Bank, the world sugar price will hover around $0.37 per kg in 2018, 12 percent below its 2016 peak. India is the world’s second largest producer of sugar, and its domestic sugar mills face downward price pressure in both international and domestic markets. According to the Department of Consumer Affairs, the domestic retail price of sugar dropped by 14 percent to $0.54 per kg in May 2018 from a high of $0.64 per kg in September 2017 (Figure 1).

E&PW (Source: World Bank)

The government’s Agriculture Statistics Division is forecasting that in crop year 2017-18 sugar production will exceed 35 million metric tons (MT), 16 percent higher than the previous year. With flat domestic consumption, the 2017-18 sugar stocks are projected to be double that of 2016-17. This will certainly result in a further glut, making it harder for mill owners to pay what they owe sugarcane farmers. Sugar mill owners must pay a government-determined base price of $0.37 to producers. At this rate, it is nearly impossible to maintain any profit margin by selling raw sugar in the domestic market.

Understanding the importance of a stable sugar price for domestic sugar mills and farmers, the government has imposed reverse stock holding limits on sugar mills, restricting the amount of sugar they can stockpile.

Exporting the surplus sugar to the deficit region of the world could be an option here. In anticipation of future growth in the export market for sugar, the government took measures such as doubling customs duties on sugar imports to 100 percent, and reducing tariffs on sugar exports to zero. The government is also negotiating sugar exports to China. However, this strategy faces problems as Indian sugar producers may face tough competition from Brazil and Thailand.

The promise of ethanol

Ethanol production is another viable strategy that may satisfy both producers and mill owners. Several government programs encourage sugar mills to produce ethanol. In May, the government announced payment of $0.08 per 100 kg of sugarcane crushed to certain sugar mills with ethanol production capacity. According to the Press Information Bureau, this program will cost $226 million—and presumably will help millers pay farmers. This could be a win-win situation for farmers, mill owners, and consumers, who would ultimately benefit from lower oil imports.

The government also mandates blending of ethanol with petroleum fuel, reaching 20 percent by 2020 (E20). However, as of 2016 that number was only 3.3 percent, far below the target of 10 percent at the time. Clearly, the government faces major challenges in meeting these targets. In addition, the current restriction on the direct use of sugar juice in ethanol production could make the implementation of the E20 mandate by 2020 even harder.

What are the policy options to meet the E20 mandates?

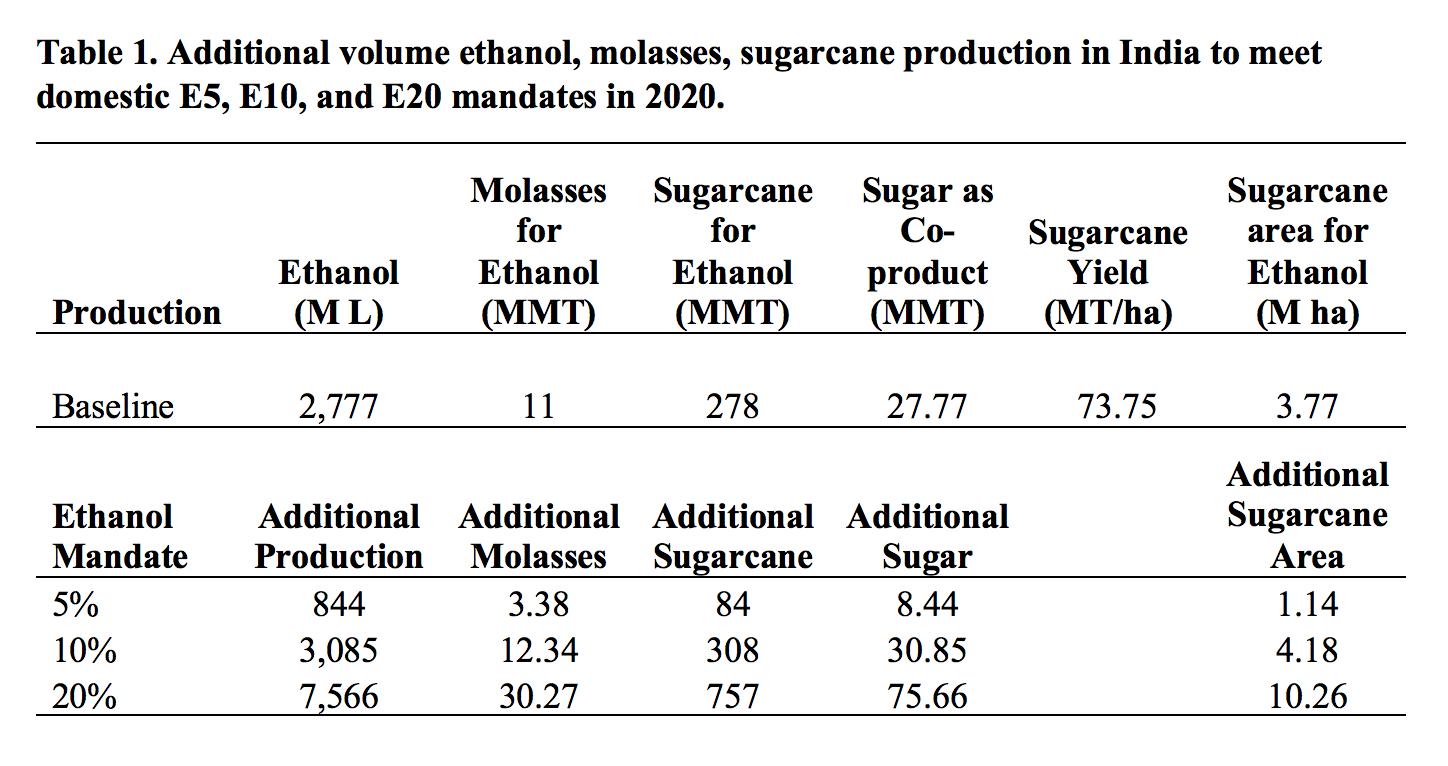

Based on the 2018 International Biofuels Baseline Briefing Book published by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at University of Missouri (FAPRI-MU), India’s E5, E10, and E20 ethanol-blending mandate scenarios are analyzed and the results are reported in Table 1.

E&PW (Source: International Biofuels Baseline Briefing Book, University of Missouri)

Under current policy, only the molasses derived during sugar production can to be used in ethanol production. The simulation results in Table 1 indicate that an additional 10.26 M ha of land would be required to meet the E20 blending mandate in 2020. Is it plausible to divert that much additional land for sugarcane production in India? Probably not.

However, achieving the 5 percent target is feasible, as mill owners can reap the benefits of the government assistance program and pay their dues to the sugarcane farmers. In the short run, there is no need for a huge increase in sugarcane acreage, as current surplus stock can be safely depleted for use in ethanol.

It should also be noted that meeting the 20 percent mandate by 2020 would require 30 million MT of molasses, and producing that could add 75.7 million MT of extra sugar to the market. That could drive down sugar prices in both the domestic and international markets. Thus, the ethanol blending program’s current targets could have serious unintended consequences.

Lessons from Brazil

Brazil has been the world’s largest sugarcane producer for many decades, and started producing cane-based ethanol as early as 1970, when a spike in world oil prices drove up its foreign debt. In order to limit that debt, the Brazilian government introduced the National Fuel Alcohol Program, known as Proálcool.

Starting in the program’s early stages, the government offered a significant subsidy to ethanol producers. Proálcool includes a high ethanol blending mandate, currently 27 percent, and requires that E100 fuel (96 percent pure ethanol and 4 percent water) or hydrous ethanol be available at the retail level. In addition, E100 can only be used in flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs), so the government provides a consumer tax incentive to purchase FFVs.

As E100 contains 70 percent energy compared to petroleum-based fuel, in order to be price competitive, E100 must be cheaper than the conventional E25 at the gas station. However, since 2000 the Brazilian ethanol market has been restructured with the government playing a minimal role, leaving the determination of ethanol prices to the market. Prices of three major commodities—sugar, gasoline, and ethanol—drive domestic ethanol production and utilization decisions in Brazil. Even though higher mandatory blending provides a buffer for ethanol producers, the volatility in hydrous ethanol use could create price movements in the ethanol market.

Brazil’s ethanol production system is unique. The majority of the country’s sugar mills are capable of producing both sugar and ethanol. Sugar processing facilities are considered biorefineries and can make sugar, bioethanol, and electricity from bagasse. These plants are flexible, producing more sugar or more ethanol depending on the price premium of one over another. This flexibility is a key reason for the Brazilian ethanol industry’s success.

What if the Brazilian sugarcane-ethanol model were replicated in India? It would have certain advantages. If the government allowed direct use of sugarcane for ethanol production, then obstacle of diverting large areas of land to cane cultivation is averted. The E20 mandate could be achieved by producing 108 million MT in additional sugarcane with an assumed yield of 73.75 MT per ha—with only 1.47 million ha of additional land required.

Other benefits would accrue. Domestic cane farmers will see the renewable energy feedstock market as an alternative to the traditional sugar market. Sugar mills with ethanol production capacity could switch between sugar and ethanol and remain profitable even if the price of one commodity fell. Such a system could help to stabilize India’s sugar market—as Proálcool did for Brazil when the sugar industry faced chronically low prices and the global oil crisis was driving up domestic petroleum prices.

Looking ahead

The Indian government’s policies to boost sugar exports likely face challenges in the form of competition from other major international players. Subsidizing sugar exports may also land India in World Trade Organization disputes with competitors. If implemented strategically, India’s ethanol blending program could be a powerful tool to stabilize sugar prices and increase farmers’ income. It can further help to reduce India’s dependence on foreign crude oil.

The government should seriously and urgently consider policies and programs that will support sugar mills in developing ethanol production and capacity. In this regard, the lessons of Brazil’s Proálcool program can be highly useful. However, the government must be careful in sequencing its interventions: At the beginning, fostering growth in the ethanol production may require public assistance; later, as the industry expands, the policies should evolve to support a transition towards a market economy.

Deepayan Debnath is an International Market and Policy Analyst in the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at University of Missouri (FAPRI-MU). Suresh Babu is Head of Capacity Strengthening and a Senior Research Fellow at IFPRI. A version of this post first appeared in Economic & Political Weekly. The authors would like to thank Patrick Westhoff for providing relevant comments on an earlier version of the article.