In many developing countries, gift-giving plays an important role in maintaining social and economic bonds. In rural China, gift exchanges are integral to guanxi, the strong social connections that affect many aspects of everyday life—including the harvest, house building, personal finance, and school choices. Gift-giving is also key to maintaining social status; many in rural China engage in conspicuous consumption to acquire and protect their rank in local society. Gifts serve as a kind of quasi-credit or insurance to build reciprocal relationships and improve public perceptions. As a result, gift-giving accounts for a large share of living expenditures in rural areas. This burden is growing: the gift to income ratio in China is now at 10% and climbing.

New research conducted in a range of villages shows the negative impacts of this gift-giving trend. It has become a kind of arms race that increases inequality, stresses household budgets and undermines overall welfare.

In rural China, gift-giving often becomes a kind of race to assert one’s status in society. Gifts are not seen merely as expressions of generosity or altruism but are constantly assessed: The value of one’s gift is compared with the value of gifts given by others. People are more likely to be perceived as true friends if their gifts are more valuable than the average gifts given by others. This creates a predicament popularly referred to in the Western world as “keeping up with the Joneses.” People must spend more and more on gifts to keep up with the rising prices of gifts given by neighbors.

Ultimately, these escalating gift expenses may crowd out spending on other, important consumption items. Between 2006 and 2011, gift expenditures in sampled villages grew by 30% per year while annual income grew by 20% (Fig. 1). To make up that shortfall, families tighten their belts, reducing expenditures elsewhere, borrowing to finance gift-giving, and even practicing risky behaviors like selling blood.

Source: Generated by authors based on their four wave Guizhou survey.

Not only does this competition distort the allocation of income between gifts and other consumption, the rising value of gifts received does not compensate for the costs associated with gifts given for other reasons. There may be “deadweight losses” associated with gifts caused by a mismatch between the preferences of the giver and recipient. For example, in the context of rural China, a welfare cost will occur because many in-kind gifts are overly “luxurious”—gift givers buy expensive food and commodities that are different from the items that they would purchase for their own consumption.

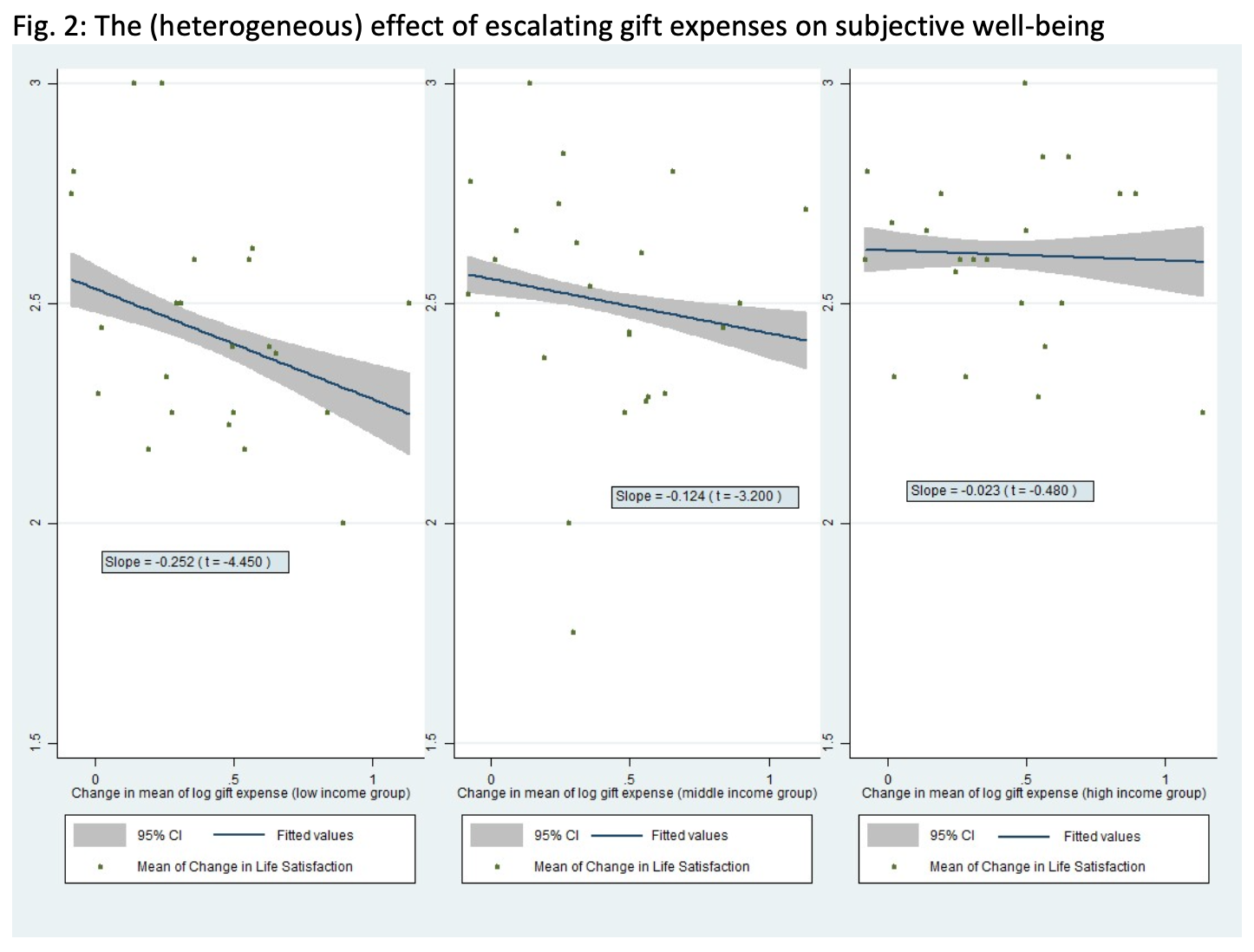

These problems have serious implications for well-being, particularly for poor families. As shown in the left and central panels of Fig. 2, low-income and middle-income households’ subjective well-being was negatively correlated with higher gift expenses. However, the giving competition has less impact on the well-being of the rich; the association between gift expenses and subjective welfare is very weak for high-income groups, as shown in the right panel of the figure. The welfare effects are heterogeneous because the escalating gift spending squeezes consumption of other goods, which is particularly costly for the poor (who have a higher marginal utility of consumption). Meanwhile, reciprocal relations are especially vital for relatively poor households, who have fewer mechanisms to smooth consumption in times of temporary hardship. However, poor households may respond more to gift competition than the rich. In another study, Chen and Zhang (2012) show that gift competition has even resulted in stunting the growth of and causing low birthweight of children born to low-income mothers when conceived in the months with greater numbers of weddings and funerals in rural villages.

Source: Bulte, Wang, and Zhang (2018).

People give gifts that aim to boost public perception and to maintain or improve their everyday reciprocal relationships. Yet, the net outcome of this activity, especially for the poor, results in lower overall well-being. Is there a way out of this trap? Potential efficiency gains and distributional benefits might be achieved if some policies, such as the restriction of extravagant weddings and funerals for government officials and Communist Party members, are introduced in order to solve the coordination problem. Once the elites stop the practice of lavish ceremonies, the ordinary people may follow and reduce the pressure for “keeping up with the Joneses.”

Erwin Bulte is a Professor of Development Economics at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. Ruixin Wang is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, China. Xiaobo Zhang is a Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division and Professor of Economics in the National School of Development at Peking University. Maxwell Young is a former IFPRI Communications Specialist. This post first appeared on VoxChina.

This study received financial support from the National Science Fund of China (NSFC).