Global patterns and local variations of COVID-19 impacts on income, food security, and dietary diversity are gradually emerging. In this post, Francisco Ceballos, Manuel Hernandez, and Cynthia Paz document these effects on the vulnerable population of the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Their findings track those in many places, including greater income losses among higher-income households but greater vulnerability among the poor. They review the policy responses and the implementation challenges in reaching rural households, and – given the pandemic’s long duration and the ambition to improve social programs – propose a follow-up study to assess longer-term impacts and lessons.—John McDermott, series co-editor and Director, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

In early 2020, Guatemala reacted swiftly to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic. It was one of the first countries in Latin America to impose strict measures to contain the spread of infection, including travel restrictions and a six-month nationwide lockdown beginning March 21 (eight days after its first reported case), comprising a temporary halt of activities in the private and public sectors, suspension of public transportation, and mobility restrictions, with a strict curfew from 6 p.m. to 5 a.m. According to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), the country’s measures were among the top five in Latin America in terms of stringency.

In a country where according to pre-pandemic statistics nearly 6 out of 10 people live in poverty and half of children under 5 are stunted, the economic and social consequences of COVID-19 and corresponding control measures deserve close attention. Moreover, Guatemala’s existing structural inequalities along cultural and geographic lines, institutional and public service deficiencies, and vulnerability to climate shocks (as shown by the devastating ETA and IOTA hurricanes in Nov. 2020), all fan the flames of this crisis and call for continuous monitoring and rapid and innovative responses.

Our recent study closely examines the short-term effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on food security and nutrition among rural households in the Western Highlands of Guatemala—possibly the country’s most vulnerable region, with the highest poverty and stunting rates and characterized by smallholder farming, low agricultural productivity, and reduced market access. The results indicate that incomes fell, food insecurity doubled, and dietary diversity declined.

The analysis relies on a comprehensive panel dataset of 1,824 small agricultural households located in the departments of Huehuetenango, Quiché, and San Marcos, collected pre- and post-lockdown during Nov.-Dec. 2019 and May-June 2020. Post-lockdown data gathering was conducted exclusively by phone, using numbers collected during the first round, and relying on community leaders to contact households that did not answer repeated phone calls, as some of them had lost or changed their numbers (a common practice in rural Guatemala).

Key findings

The lockdown’s direct economic consequences are evident at first glance: Almost two thirds of the interviewed households reported a decrease in agricultural and non-agricultural income (the latter being sharper), while the large majority (94%) reported decreased remittances received, consistent with national reports during the first months after the outbreak. On aggregate, roughly three out of every four households reported an unambiguous decrease in income.

Despite the relatively quick rollout of government support programs, the study finds that poor households mostly relied on limited coping mechanisms to deal with these income reductions. This, together with reported reduced food availability and higher food prices in local markets (a result of disruptions in trade and logistics and labor shortages, despite the agricultural sector’s official exemption from lockdown restrictions), appears to have reduced households’ food security and dietary diversity.

The prevalence of food insecurity roughly doubled between the end of 2019 and mid-2020, the survey indicates. This pattern was observed consistently across all forms of food insecurity: Mild (having eaten only a few kinds of foods because of a lack of money or other resources), moderate (having eaten less than they thought they should), and severe (not having eaten despite feeling hungry).

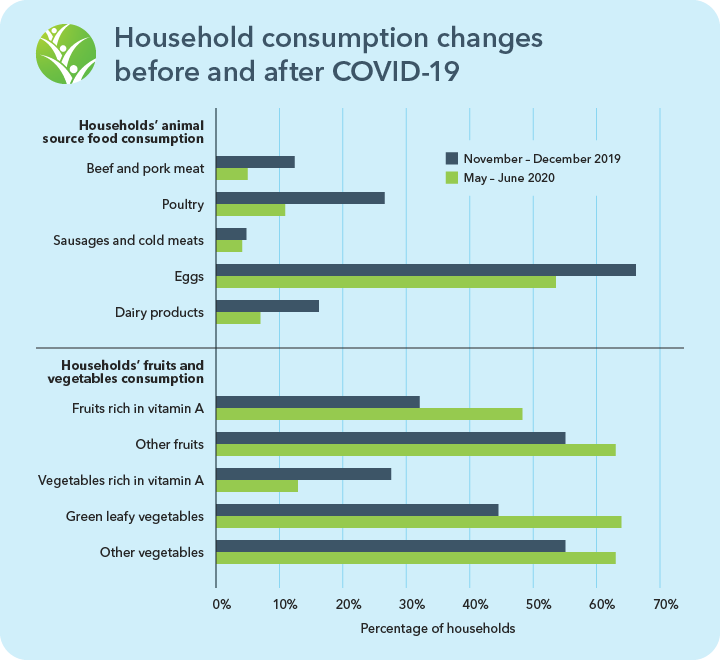

In addition, household dietary diversity fell overall, as indicated by a small but statistically significant decrease from 6.9 to 6.4 in the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDSS), defined as the number of food groups consumed—ranging from 0 to 12—in the 24 hours preceding the interview. Households seemed to switch away from consumption of animal-sourced foods towards greater consumption of fruits and vegetables, with no significant changes observed in other food groups, such as cereals and grains or legumes and nuts. Unfortunately, the data did not permit to determine net changes in nutrient intake brought about by this dietary switch, as quantities consumed were not collected during the surveys.

At the individual level, dietary diversity among women 15-49 remained unchanged at around 4.5 (on a range of 0-9 food groups) and increased among children 6-23 months old from 3.3 to 3.9 (on a range of 0-7 food groups). This points towards potential changes in intra-household allocation of foods in response to a shock, where young children could have been prioritized.

Interestingly, the study indicates that higher income households reduced their dietary diversity more than lower-income ones, and were also more prone to report a decrease in income. The lockdown may thus have had relatively greater impacts on higher vs. lower-income households, which tend to depend more on subsistence farming and other small scale, locally-oriented activities less affected by the restrictions. Nonetheless, the latter could still have been worse off in absolute terms, and exhibit additional vulnerabilities along several dimensions—acute malnutrition, for example, more than doubled in Guatemala over the months after the start of the pandemic compared to same period in 2019. Households located in communities that imposed additional access restrictions during the lockdown (over 75% of those sampled) also showed a larger decrease in their dietary diversity compared to those in communities that did not.

Policy responses and looking forward

Starting in April 2020, the government of Guatemala scaled up programs to contain the negative effects of the crisis on livelihoods and food security. These included greater support for micro, small, and medium enterprises, subsidies for public services, and price controls on foods included in the basic food basket. Two COVID-19 programs provide direct assistance to vulnerable rural and urban families: the Programa de Apoyo Alimentario (Food Support Program) distributes rations, prioritizing the procurement of basic grains from smallholder farmers; the Bono Familia provides an emergency supplementary monthly income of around $130. Despite these efforts, the study shows the assistance may not be reaching many of its intended recipients. While six out of every ten communities received some form of public or private aid (as reported by community leaders), only two out of every ten households reported receiving aid. This suggests the need to intensify efforts to reach a larger share of rural households affected by COVID-19.

Overall, the study suggests a complex array of impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic and control measures in the nutritionally compromised context of Guatemala’s Western Highlands: Decreases in household food security and overall dietary diversity following reported reductions in income, price increases, and lower food availability at local markets. While the pandemic impacts continue to evolve and present ongoing challenges, our findings call for a closer and continuous look at the conditions rural families in the region face, together with their responses. As a result, we plan a second, follow-up survey for May-June 2021 to assess longer-term variations on food security and nutritional patterns.

Francisco Ceballos is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Manuel Hernandez is an MTID Senior Research Fellow; Cynthia Paz is an MTID Research Analyst. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors. This paper is part of a COVID-19 special issue of Agricultural Economics edited by IFPRI’s Johan Swinnen and Rob Vos.

The study was funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).