IFPRI’s picture-based insurance (PBI) initiative, recognized as a CGIAR@50 Innovation and active since 2016, relies on participating farmers to upload smartphone pictures of their fields at intervals throughout the growing season. In the event of bad weather, pests, disease, or other problems that harm the crops, the photos are used to assess the damage and trigger insurance payouts.

More recently, a new service has been added: The photos can serve as the basis for low-cost, interactive picture-based advisories (PBA)—expert advice tailored to individual farmers—enabling unprecedented levels of targeting and timeliness in remote agricultural extension activities.

Coupling advisories with insurance can reduce barriers to technology adoption and lower overall farming risk by encouraging improved agricultural practices. Beginning in 2022, CGIAR’s Standing Panel on Impact Assessment (SPIA) has funded an impact evaluation of PBA in India and Kenya to evaluate its effects on a range of farming and welfare outcomes and shed light on the system’s scalability.

How did we go about setting up a well-functioning system of remote advisories, personalized to each farmer’s situation, with little automation or heavy human involvement? This post describes our journey for designing this system, a description of its day-to-day functioning in Kenya, and the lessons learned throughout this process.

Designing the service

The project’s initial goal was to be able to deliver a single advisory message by local agronomic experts every 14 days to all of the nearly 1,400 farmers in Kenya participating in PBI. Advisories are based on any issues observed in pictures each farmer has submitted in the previous 14 days, informed by the experts’ knowledge of the crop, common management practices and availability of inputs in the area, recent or forecasted local weather, and current issues experienced by other area farmers.

If a farmer has not submitted any pictures in the past 14 days, the advisory takes into account pictures submitted by neighboring farmers. If those images are not available, a standard advisory is sent based on general patterns observed in the region, current weather forecasts, and/or information on upcoming practices according to the crop calendar. When no damage or problems are visible in the crop photos, and no broader issues observed in the region, an encouraging message is sent to the farmer confirming the good condition of their crop.

To set up the infrastructure for this system, our team of app and website developers updated the PBI app with functionality for receiving advisory messages and upgraded the website that served as the app’s back-end and as a portal for direct communication with farmers.

A team from the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) took responsibility for monitoring incoming pictures and issuing advisories. Each advisory message is sent through two channels: an incoming advisory tab within the smartphone app, and a SMS text.

When drafting advisory messages, experts can use existing templates, create new templates for common problems observed in the area, or write an individual message from scratch. After sending each advisory, experts answer a short web-based questionnaire including the general topic of the advice, the problem identified in the pictures, the specific practices/technologies they recommended, and whether the advice was of a preventative or curative nature.

Results in 2022

At the end of the Long Rains 2022 season, we interviewed the two participating KALRO experts, who reported that farmers’ uploaded images were consistently good enough to enable them to identify specific problems in the crops and provide pertinent advisories. For example, while nutrient deficiency, excess water, and certain diseases can all lead to the yellowing of crop leaves, experts were able distinguish these problems from the photos by looking at other elements—such as the condition of the surrounding soil, close-ups showing telltale signs of a given disease, or noting that nitrogen deficiency results in the gradual yellowing of leaves beginning with those closer to the ground.

Other conditions such as drought could be identified by observing the dryness of the soil and an overall dry, dusty environment in the picture. This highlights the value added of looking at ground pictures of the crop vs. other competing approaches, such as satellite-derived vegetation indices that rely on leaf color alone, with little additional information on its underlying causes.

Experts sent close to 5,000 advisory messages throughout the season covering a range of topics (Figure 1), with the majority of advice relating to the presence of weeds in the fields, the presence of pests or diseases, and a lack of water or the need to irrigate the crop.

Figure 1

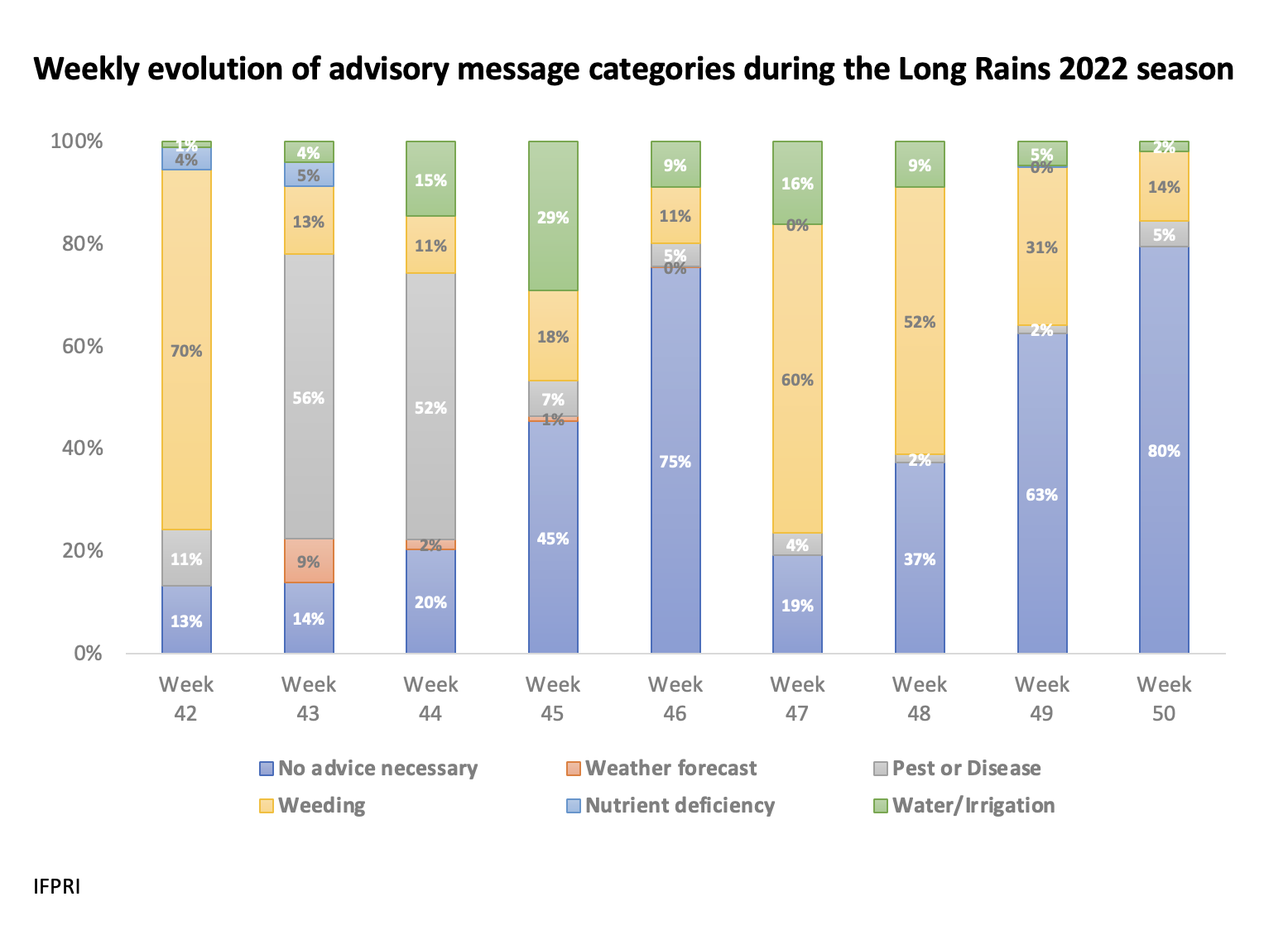

The advice varied across farmers and also evolved with the season (Figure 2), reflecting changing problems and needs as the season unfolded, related for instance to recent weather, the propagation of different pests, and different needs stemming from the natural progression of the crop calendar. For example, more than half of the messages sent during the second and third weeks of the growth season were related to the prevention and treatment of fall armyworm and maize stalk borers, but in subsequent weeks, less than 5% of the pictures reflected issues with pests.

Figure 2

Finally, we found that a system of personalized advisories is able to adapt to changing geographic trends in crop stress and overall growth conditions. To illustrate this, Figure 3 shows evolving instances of the two main pests (maize stalk borer moths and fall armyworm) and of lack of water or drought (the most common abiotic challenge) that affected crops during the season, as observed from farmers’ pictures of their fields.

Figure 3

A few patterns emerge in the time-lapse, with fall armyworm detected in the westernmost study villages during late October, then mostly shifting to the easternmost study villages during early November, and reappearing in mid- and late November in specific hotspots almost exclusively in the west of our study area.

Drought, on the other hand, was observed mostly in the easternmost villages, and particularly in the last few weeks of November. This level of tailoring to observable, real-time crop conditions would simply not be possible with the standard, generic advisories delivered by most digital advisory services.

Farmers themselves echoed the advantages of a personalized advisory system. Preliminary qualitative evidence from informal phone interviews with participating farmers during the season indicates that most were happy with the PBA advisories, found them timely, useful for improving crop practices, and employed them as reminders for implementing upcoming recommended practices according to the crop calendar.

Next steps

The project is expected to continue into 2023 for two additional agricultural seasons, allowing for potential improvements.

First, currently farmers due for advice are not organized geographically in the website interface, making it hard for experts following geographic pest or weather patterns to provide location-specific advice—a problem that can be addressed by upgrading the site.

Second, we plan to assess the feasibility of implementing a text message chat function to facilitate farmer communication with experts—for instance, if they want additional information or to resolve doubts about the advice received. This app functionality is currently available in India, but not yet in Kenya, where champion farmers (specially trained farmers who own a smartphone, coordinating study activities directly with our fieldwork team) are responsible for taking pictures on behalf of other farmers in each study village. Instead, farmers have been able to call KALRO’s toll-free call center to discuss such concerns, though this does not connect them directly to the expert who provided the advice.

Finally, during the 2022 season some farmer phones did not accept incoming text messages, a problem stemming from a national regulation allowing cellphone customers to opt out of receiving commercial SMS. Addressing this issue will require fieldwork efforts to convince farmers to opt-in to our SMS service.

All in all, despite some implementation issues, this was a promising first season for picture-based advisories in Kenya. Substantial effort went into the IT infrastructure needed to support the agricultural experts providing the advice, and into addressing the needs of farmers and sorting out specific hurdles in the Kenyan context. These efforts paid off by allowing experts to deliver highly personalized advice completely remotely, informed by a host of visual cues from pictures, and high satisfaction with the service as reported by participating farmers. We plan to continue efforts to develop the PBA system—a model that has the potential to revolutionize the way agricultural extension services are provided in Africa and much of the developing world.

Francisco Ceballos is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division (MTID); Berber Kramer is an MTID Senior Research Fellow based in Nairobi; Benjamin Kivuva is Assistant Director, Crop Production and Seed System at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO).

This work is part of the CGIAR Initiative Ukama Ustawi: Diversification in East and Southern Africa.