Global fertilizer markets experienced significant price surges beginning in 2020 and through 2022 due to a combination of factors, including higher natural gas prices, supply chain disruptions triggered by COVID-19, trade disruptions due to the Russia-Ukraine war, and export restrictions. Although parallel increases in international agricultural commodity prices may have cushioned these price shocks, insufficient availability and affordability of fertilizers are likely to have affected yield and profitability of smallholder production systems. Whereas international prices have come down from their peaks, many countries continue to grapple with persistent inflation, deteriorating terms of trade, and macroeconomic imbalances, which are keeping domestic fertilizer prices high. While these impacts may vary by country depending on fertilizer availability and farm households’ purchasing power, smallholder farmers are likely to face the brunt of these challenges given the already limited access to fertilizer markets and resources, including in the focus country of this post, Ethiopia.

For many African countries south of the Sahara, fertilizer application had only slowly increased prior to this spike in food and fertilizer prices. Sub-Saharan Africa consumes about 11-12 million metric tons of chemical fertilizers, accounting for about 3%-4% of total global consumption. As of 2018, fertilizer application in Africa averaged 22 kg/ha of nutrients, a long way from the goal of applying 50 kg/ha by 2015, as endorsed by heads of state in the Abuja Declaration on Fertilizer for the Africa Green Revolution. Indeed, even before the Russia-Ukraine war, many countries were lagging way behind these targets and out of 51 African Union Member States reporting on this indicator, only five (Egypt, Ethiopia, Morocco, Seychelles, and Tunisia) were on track to meet this target.

Smallholder agriculture in Ethiopia, as in many African countries, relies on imported fertilizers. Employing about 80% of the population (15.6 million farm households), Ethiopia’s agriculture accounted for 37.6% of GDP in 2022. Given high levels of soil nutrient depletion, intensified use of fertilizers is critical for increasing agricultural productivity and structural transformation. While the country made significant stride in improving the adoption of fertilizer and crop yield growth by smallholder farmers, application rates remain low for many crops.

Whether and how much recent fertilizer supply disruptions and price spikes might have decreased fertilizer application by smallholders is difficult to establish, given the paucity of real-time data, but these problems likely presented substantial challenges. These include higher production costs triggered by higher input prices, reduced agricultural yields due to reduced fertilizer use, and possibly increased vulnerability to crop failures due to pest infestations, diseases and adverse weather conditions as undernourished crops are more vulnerable to abiotic and biotic stresses. Farmers may also adapt to higher fertilizer prices by switching to crops with lower nutrient requirements, which can ultimately affect national food security. Uncovering these potential responses and trade-offs requires real-time household-level data on local prices, availability and application rates, which remains scarce in the case of smallholder agriculture in Africa.

Here, we aim to shed light (and provide some descriptive evidence) on these issues by combining different datasets, including large longitudinal household data collected before and after the crisis. Findings include:

Surges in domestic fertilizer prices may be larger than increases in international fertilizer prices. Fertilizer and fuel importing regions such as Africa had to contend not only with the increase in global food, fuel, and fertilizer prices, but also with domestic challenges leading to further price increases. For instance, a rapid assessment conducted by the Ministry of Agriculture in Ethiopia and Stichting Wageningen Research Ethiopia shows that local fertilizer prices have recently jumped by about 170% between 2020 and 2022 (from 27,735 birr/ton in 2020 to 47,150 birr/ton in 2022). Increasing food prices can help farmers offset higher fertilizer prices, but this is less likely in areas remote from both input and output markets. Price increases of this magnitude can therefore impact adoption and potentially trigger yield losses and food insecurity.

Using longitudinal data coming from the Livings Standards Measurement Survey-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) collected by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia and the 2023 Agricultural Commodity Clusters (ACC) survey collected by IFPRI, Figure 1 shows the steady increase of food and fertilizer prices in Ethiopia. Food prices started increasing well before the global food-fuel-fertilizer crisis in 2020s, but the most striking increase in fertilizer and food prices was triggered by the Russia-Ukraine crisis (Figure 1). For example, food prices for important cereals such as teff doubled in the past four years, 2019-2023, while fertilizer prices increased by more than threefold between 2019 and 2023.

Figure 1

Source: Livings Standards Measurement Survey-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA). The 2023 prices are based on the 2023 Agricultural Commodity Clusters (ACC) survey.

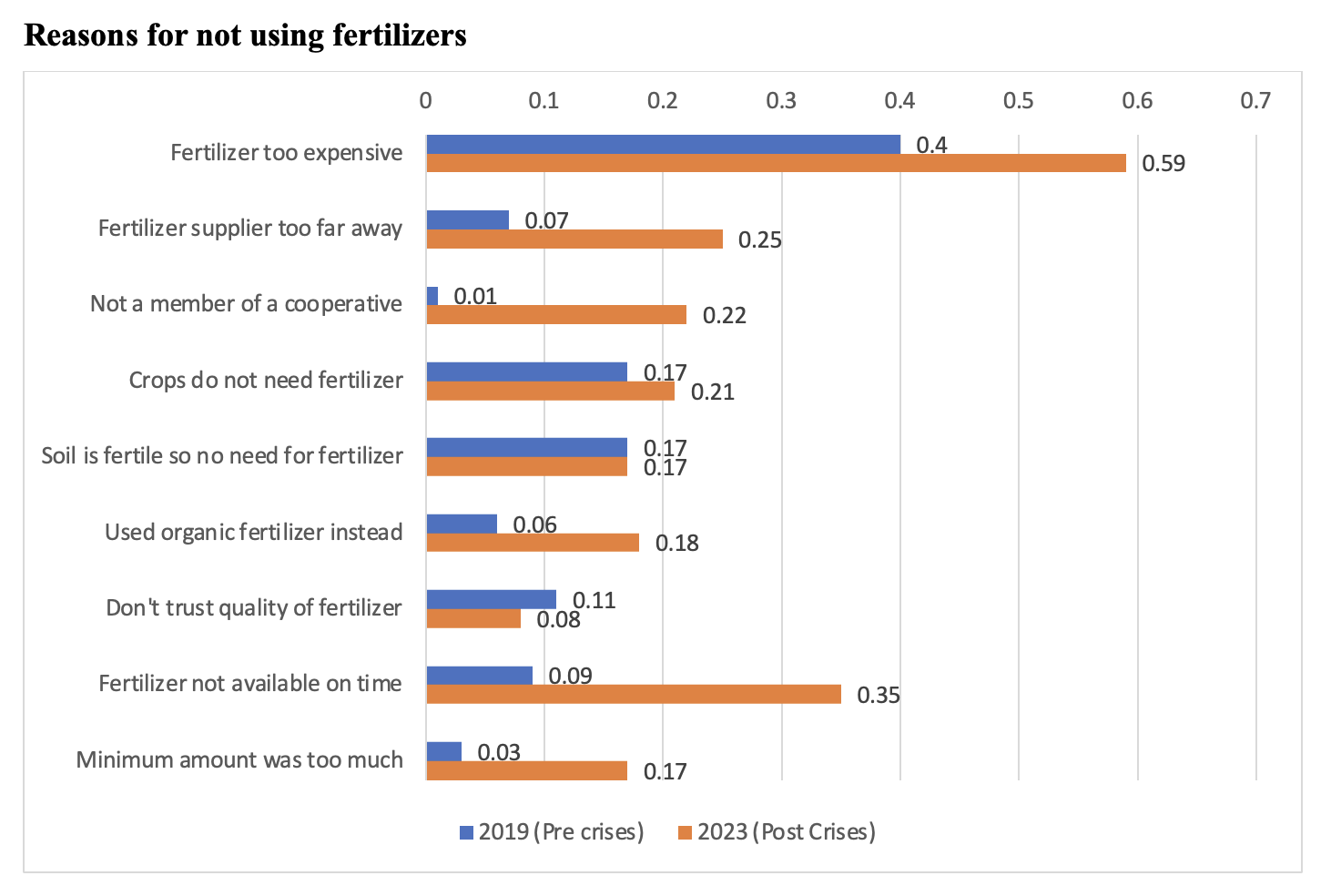

Affordability of chemical fertilizer remains the most important reason for non-adoption of inorganic fertilizer. Some 59% of smallholders surveyed in the ACC survey point to prohibitive fertilizer prices as the main reason for not applying fertilizers on their plots (up from 40% in 2019). Another 35% of households report availability as a major factor for non-adoption in 2023 versus 9% in 2019. Also of note is that 22% of farmers cite not belonging to an agricultural cooperative (versus 1% in 2019), and some 25% of farmers attribute the distance from fertilizer markets (versus 19% in 2019) as their main reasons for not using fertilizers. We note that the Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA) has worked with the private sector to pilot one stop input shops to improve the delivery of fertilizers to farmers in remote areas, but it is possible that these profit driven shops drive up prices even more, as anecdotally observed during the 2023 survey. Lastly, the surge in fertilizer price seems to have encouraged farmers to shift to organic fertilizers as the share of farmers reporting such a reason triples from about 6% in 2019 to 18% in 2023.

Figure 2

Source: 2023 Agricultural Commodity Clusters (ACC) survey.

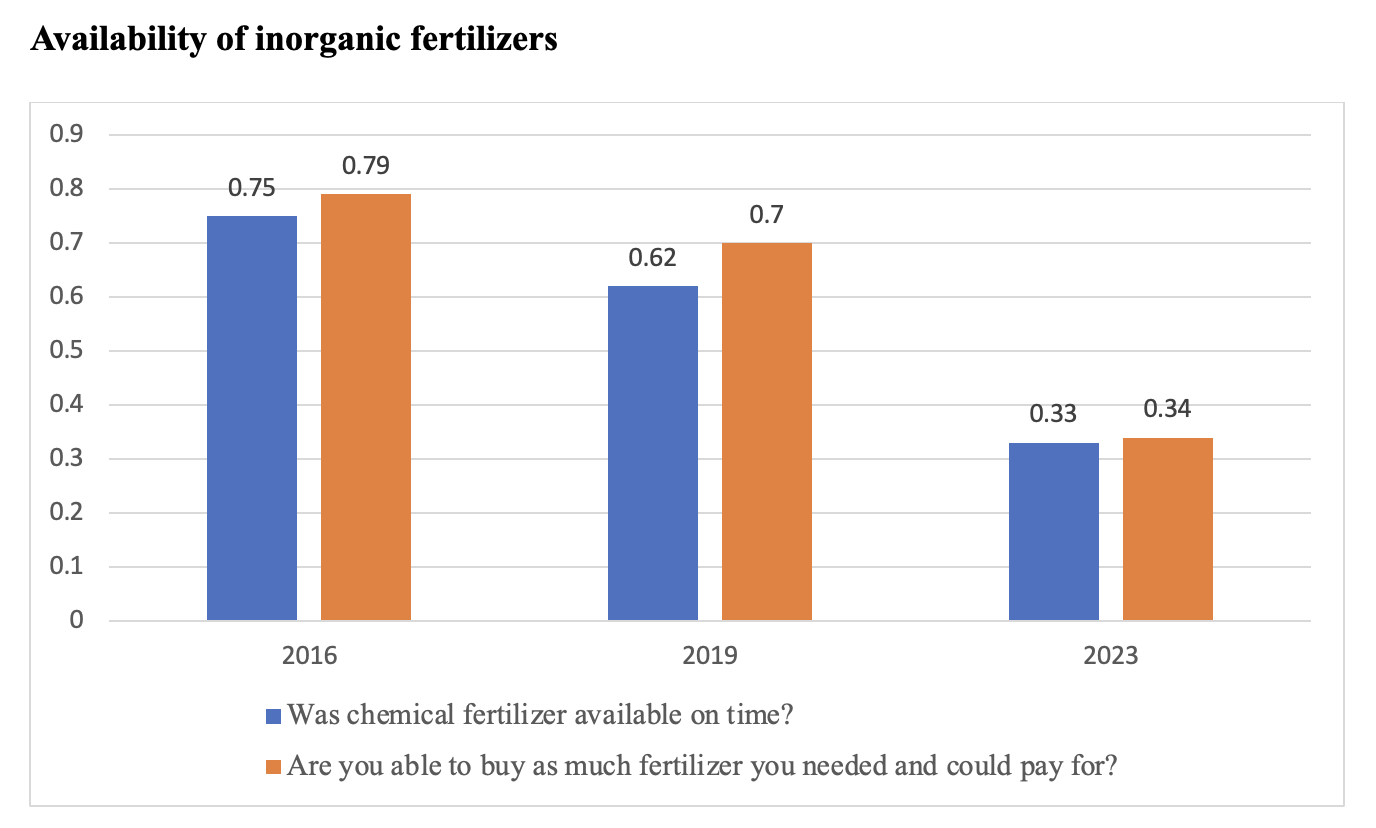

Domestic availability of fertilizers was perceived as a major challenge. Besides the surge in domestic price of fertilizer, smallholder farmers faced actual fertilizer shortages triggered by supply chain disruptions unleashed by the Russian-Ukraine and internal conflicts. The ACC survey elicited important information on the availability of chemical fertilizer in each round of the survey. As shown in Figure 3, availability of chemical fertilizers declined in 2023, after the crisis. Only 33% of households report that fertilizer was available on time (a 29 percentage point decline over 2019), and only a third report buying as much as they needed and could afford in 2023, about half of the corresponding share reported in 2019 and 2016.

Figure 3

Source: 2023 Agricultural Commodity Clusters (ACC) survey.

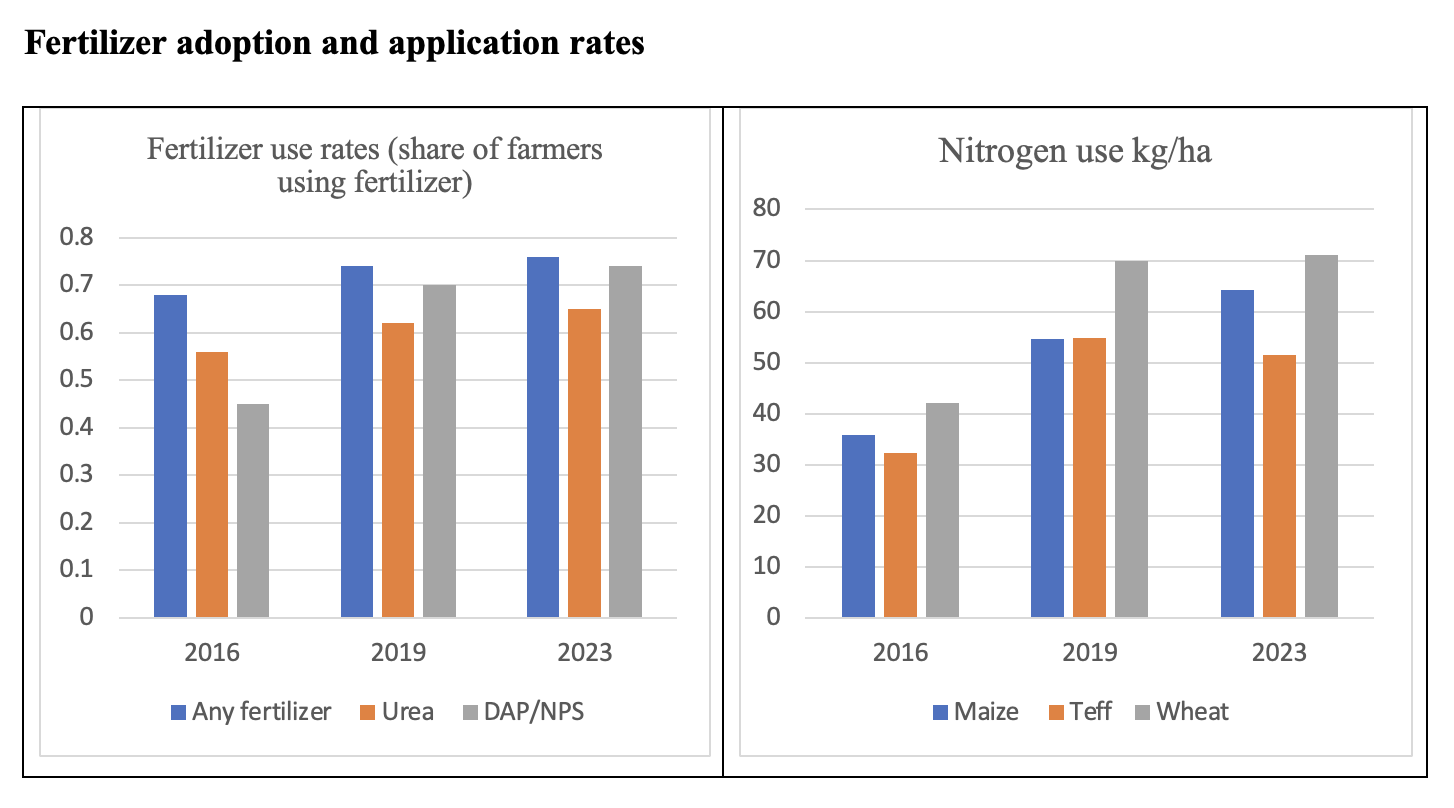

While 2023 fertilizer use and application levels, as indicated in the ACC survey results (Figure 4) did not fall below 2019 levels, the compounding crises seem to have halted the growth of fertilizer use observed between 2016 and 2019.

The share of farmers using fertilizer in Ethiopia has been significantly increasing over the last decade. However, this trend has slowed following the recent global as well as local crisis. As also shown in Figure 4, nitrogen application rates were increasing up until the crisis, but then stagnated at previous rates. Potentially due to parallel increases in output prices, at least no decrease in nitrogen use was observed.

Figure 4

Source: 2023 Agricultural Commodity Clusters (ACC) survey.

Domestic crises and armed conflicts may be contributing to supply disruptions in fertilizer markets. Another follow-up IFPRI community-level survey in more than 90 districts and 180 villages in high and low agricultural potential areas in Ethiopia reveals that about 60% of community leaders report that conflict affected the distribution and availability of fertilizer in their villages. Other actors in agricultural value chains, and the broader rural economy, are also likely affected by these shocks, and the country’s agricultural sector may be set back. Given the importance of agriculture in the overall economy, and the important role agricultural inputs and technologies have played in Ethiopia’s agricultural growth, these trying years may also lead to a deterioration of national food security.

Kibrom Abay is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance Unit; Thomas Assefa is a Visiting Research Scholar at the University of Georgia College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences; Guush Berhane is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling Unit; Gashaw T. Abate is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit; Charlotte Hebebrand is Director of IFPRI’s Communications and Public Affairs Unit. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

This work is part of the CGIAR Research Initiative on National Policies and Strategies (NPS). CGIAR launched NPS with national and international partners to build policy coherence, respond to policy demands and crises, and integrate policy tools at national and subnational levels in countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. CGIAR centers participating in NPS are The Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (Alliance Bioversity-CIAT), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI),International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), International Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Potato Center (CIP), International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), and WorldFish. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. The data and research in this blog also benefited from research funding from USAID under the project “Monitoring and Analyzing Immediate Impacts from the Ukraine War”, which the authors gratefully acknowledge.