Smallholder farmers in northeastern Nigeria face interrelated challenges of food insecurity, climate change impacts, and conflict. The region has some of the country’s highest levels of food insecurity, and increasingly volatile rainy seasons have led to massive floods, depleted soil quality, and disrupted agricultural growing seasons.

Moreover, millions in the region have fled their homes due to conflict between pastoralist livestock herders and settled agricultural communities over land use and religious extremism. Exposure to conflict itself contributes to reduced agricultural production and increased food insecurity. Studies also indicate a decade-long increase in conflict levels, where poverty is associated with sustained conflicts. Northeastern Nigeria has been particularly affected, with 49% of households experiencing conflict between 2010 and 2017.

Thus, there is a strong need to improve agricultural productivity and address food insecurity in northeastern Nigeria—and more broadly around the world. A common policy tool is providing subsidies or discounts for agricultural inputs. However, significant gaps in data and research exist on the effectiveness of such programs in areas affected by conflict.

Specifically, while existing evidence shows that discount vouchers effectively promote demand for agricultural inputs in stable and conflict-free settings, we do not know the extent these results persist in fragile and conflict-affected settings. It is possible that people living in such settings—particularly those who have been directly affected by conflict and forcibly displaced—face greater liquidity constraints and require larger discounts. But it is also possible that interventions focusing on agricultural production make little sense in contexts where conflict is so intense that farmers are forced to migrate away from their farmland.

An ongoing randomized controlled trial in northeastern Nigeria allows us to directly investigate how providing discount vouchers affects demand for agricultural inputs among people living in a fragile and conflict-affected setting, and more specifically, people who have been forcibly displaced. (See our earlier post on this study’s preliminary results on the timing of take-up.)

In this study, we partnered with a local agricultural input dealer to promote the purchase of a bundle of agricultural inputs—including biofortified seeds, fertilizer, crop protection products, and insurance—among smallholder farmers. We designed an intervention using two main promotional tools commonly employed by agricultural input dealers: Marketing campaigns and price discounts. A total of 2,300 farmers from 230 communities in Gombe State, Nigeria were randomly assigned, at the community level, to one of the following four groups:

- Treatment 1: Marketing information only

- Treatment 2: Marketing information + 50% discount vouchers

- Treatment 3: Marketing information + 75% discount vouchers

- Control: No marketing information or discount vouchers

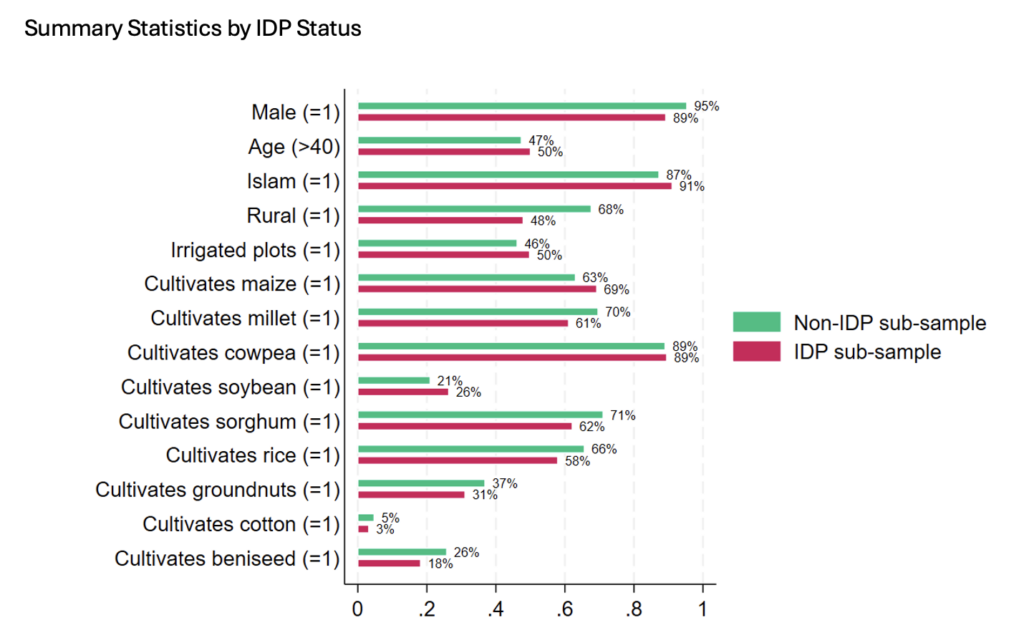

This experimental design allows us to study the effect of marketing information plus the additional effects of two different price discount levels on take-up rates of the bundle of agricultural inputs. In this preliminary analysis, we focus on take-up, defined as whether the farmer purchased the bundle within the time frame of our study. We define internal displacement as having occurred if a household reported relocation at any time in the past. Based on this definition, we classify 17% of households (n=380) in our data as being home to internally displaced people (IDPs). It is important to note that despite their displacement, as noted in Figure 1 below, the IDPs in our data have access to land and can cultivate it to produce crops for both their own consumption and local marketing.

Figure 1 reports summary statistics by IDP status. Households consisting of people we classify as IDPs are six percentage points less likely to be headed by a male (p-value = 0.004) but are similarly aged (p-value = 0.446) and are just as likely to report Islam as their main religion (p-value = 0.202) compared to households without IDPs. Notably, households in the IDP sub-sample are nearly 20 percentage points less likely to live in a rural area relative to households in our non-IDP sub-sample (p-value = 0.001).

Figure 1

This rural-urban gap suggests that characteristics of agricultural production might differ between households with IDPs and those without displaced residents. This is indeed what we observe. Although the share of households with plot irrigation is similar (p-value = 0.323), households with IDPs are six percentage points more likely to cultivate maize (p-value = 0.083) and nearly nine percentage points less likely to cultivate millet (p-value = 0.029), nine percentage points less likely to cultivate sorghum (p=value = 0.009), eight percentage points less likely to cultivate rice (p-value = 0.057), and seven percentage points less likely to cultivate beniseed (sesame) (p-value = 0.009) than households without IDPs. Meanwhile, there is no significant difference in the likelihood of cultivating cowpea (p-value = 0.838), soybeans (p-value = 0.149), groundnuts (p-value = 0.118), or cotton (p-value = 0.242) between these two groups.

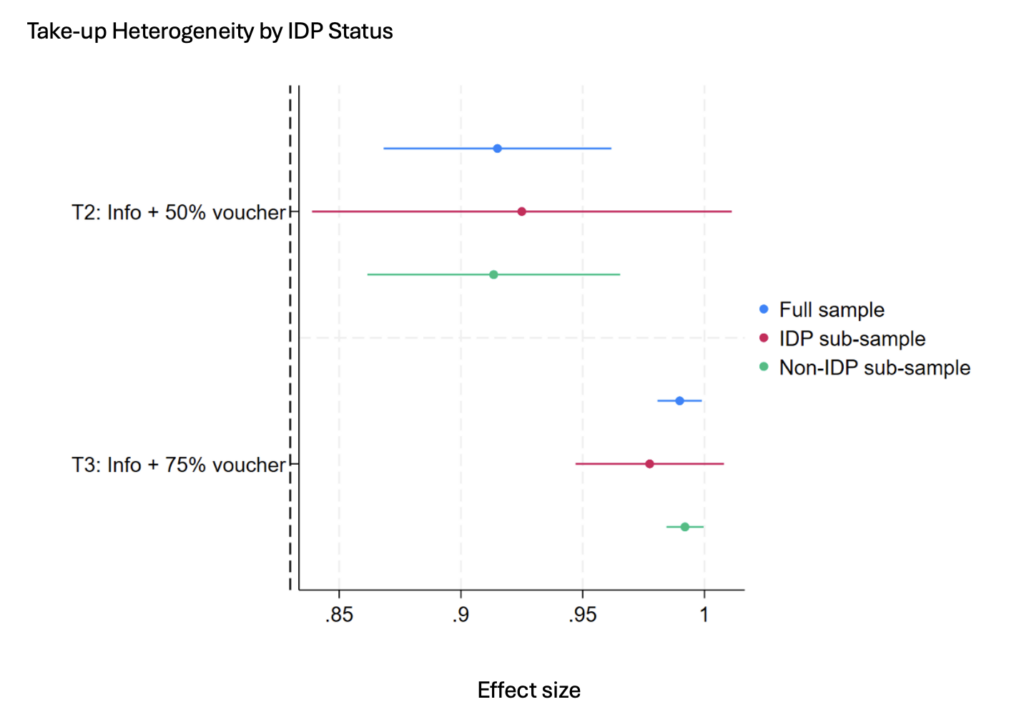

These differences in household and agricultural production characteristics between households with IDPs compared to households without IDPs demonstrate the potential for treatment effect heterogeneity within our randomized control trial. To assess this, we report regression results in Figure 2, where the x-axis records the effect size. The blue dots represent effect estimates for take-up for each treatment using the full sample, while the red and green dots represent effect estimates for the IDP and non-IDP sub-samples, respectively.

Figure 2

In our full sample, we find that no households in treatment group 1, which received only marketing information, purchased the bundle during the study period. This lack of uptake may be attributed to price volatility in agricultural inputs—especially fertilizer—during the implementation of our study. In contrast, in treatment groups 2 and 3, where farmers received a discount voucher, over 90% of farmers purchased the bundle during the study time frame.

Despite the differences in household and agricultural production characteristics, we observe qualitatively similar results in both the IDP and non-IDP sub-samples. Specifically, 93% of farmers categorized as IDPs in treatment group 2 purchased the bundle, compared to 98% in treatment group 3. Similarly, in the non-IDP sub-sample, 91% of farmers in treatment group 2 and 99% in treatment group 3 purchased the bundle.

These findings are important for at least two reasons. First, the take-up rates observed are more than twice as high compared to those from a similar study, implemented in a stable and conflict-free setting, where price discounts were offered for the purchase of an agricultural inputs bundle. This suggests that demand for agricultural inputs can be relatively elastic in fragile settings. Second, our price discounts—especially the 50% discount—are comparable in magnitude to existing agricultural input subsidy programs implemented by the national and local governments in Nigeria.

In future analysis, we will study outcomes beyond take-up and explore if outcomes such as agricultural production and consumption patterns change in line with the random assignment to the treatment in our experiment. This will enable insights into the contextual factors within fragile and conflict-affected areas that either enable or prohibit the successful implementation of development interventions. More generally, these findings will enable us to contribute to a better understanding of how to best design development interventions and marketing strategies in fragile and conflict-affected areas, where most people living below the global poverty line increasingly live.

Mulubrhan Amare is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit; Temilolu Bamiwuye is a DSG Research Analyst, based in Nigeria; Kate Ambler is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Jeff Bloem is an MTI Research Fellow; Rewa Misra is the Head of National Policy and Innovative Financing in the HarvestPlus section of IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling Unit.Julia Wagner is an MTI Research Analyst. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed.

Support for this work was provided by the CGIAR Initiative on Fragility, Conflict, and Migration and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad).