Agriculture is central to Malawi’s economy, employing much of the population and contributing substantially to GDP. However, agricultural productivity and earnings have stagnated and chronic food insecurity is a serious problem. Recent shocks including the COVID-19 pandemic, higher food prices, and cyclones have hurt agricultural production and hindered Malawi’s progress toward SDG target 2.3 (double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers).

Digital tools can help boost smallholder productivity and incomes by providing timely and targeted agricultural advice, facilitating access to markets, improving crop management practices, and enhancing overall agricultural decision-making.

To accelerate and realize the potential of digital agriculture, Farm Radio Trust-Malawi (FRT) is providing a low-cost and wide-coverage information and communications technology (ICT) intervention bundle to existing producer groups. Participants receive weekly phone messages (SMS) on agricultural management and marketing; watch videos on agricultural techniques; and are encouraged to use a hotline/call center for agricultural and market advice, to set up radio listening clubs, and to practice collective marketing. The overall aim is to create ICT hubs with members who are active ICT users and promoters, adopters and models of good agricultural and marketing practices, and beneficiaries of improved productivity and incomes.

An IFPRI evaluation of the ICT hub interventions, a randomized-controlled trial, showed mixed results, with some statistically significant increases on income and awareness and use of digital tools among those who received in the interventions in two of five districts. However, the program appeared hindered in many areas by farmers’ limited access to mobile phones and other factors.

The reach of digital technologies in Malawi is limited but has been expanding: 50%-60% of the population had access to mobile phones and 18%-28% had internet access in the last five years. While most of the mobile phones in use have only basic features and operate on 2G networks, the use of smartphones on 3G and 4G networks is increasing, even in Malawi’s rural areas.

A number of digital extension services are available in Malawi, including Access Agriculture’s focus on video-based extension, Viamo’s agriculture extension support through a mobile phone service called 3–2–1, and a call center/hotline operated by FRT for agriculture and rural development issues. Yet national surveys show that less than 3% of rural households report using these digital tools and services, and most farmers still rely primarily on traditional sources, like radio and government extension, for agricultural and market information. Thus the FRT program is an attempt to leverage the promise of expanding mobile phone use and ICT.

The study

IFPRI designed its evaluation study as a cluster-randomized controlled trial in five districts. Of 118 existing producer groups identified, half were randomly assigned as treatment groups receiving the ICT intervention bundle and half as control groups. The interventions were first implemented in the 2021/22 farming season and then in the 2022/23 farming season. We conducted a baseline survey in July-August 2021 and a follow-up survey in August-September 2023. Key informant interviews and focus group discussions in July 2023 and February 2024 complemented the survey data.

Positive impacts

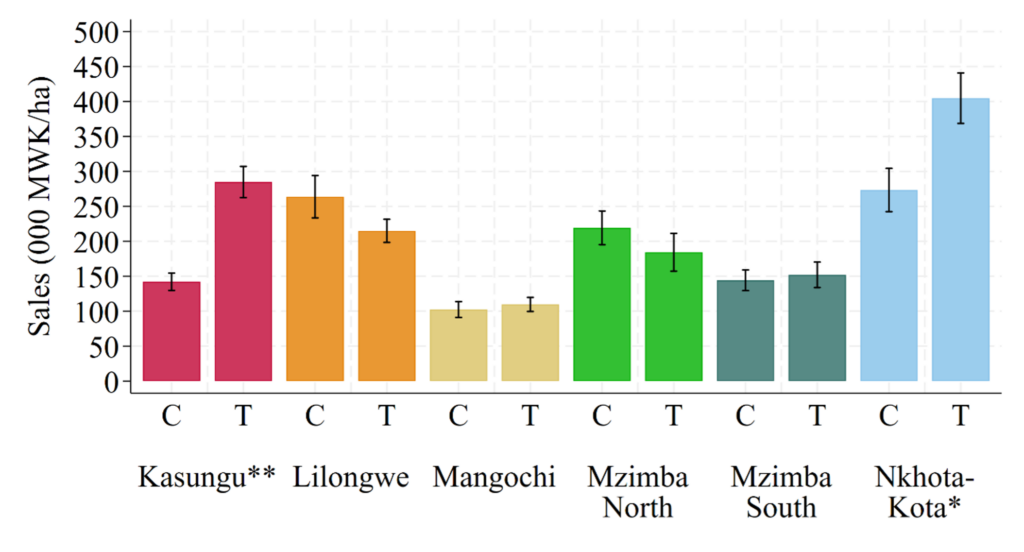

1. Small increase in farm income. The interventions led to small positive increase in crop income (MWK 75,000 or $65 per household; MWK 51,000 or $43 per hectare (ha) on average). Treatment households in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota experienced a higher increase in farm income (Figure 1). In Kasungu, the impacts are larger: MWK 420,000 or $361 per household on average; MWK 130,000/ha or $111/ha on average. This is mainly due to more soybean and groundnuts produced and sold and higher prices received due to collective marketing. In Nkhota-kota, the effect is MWK 200,000 or $172 per household on average; MWK 170,000 or $146/ha on average, mainly due to the shift to rice and soybean from maize, greater volume of sales, and some effect of collective marketing.

Figure 1. Crop income increased in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota

the vertical lines in the bars are the standard errors. Statistically different at †0.15, *0.10, ** 0.05, and *** 0.01 level of significance.

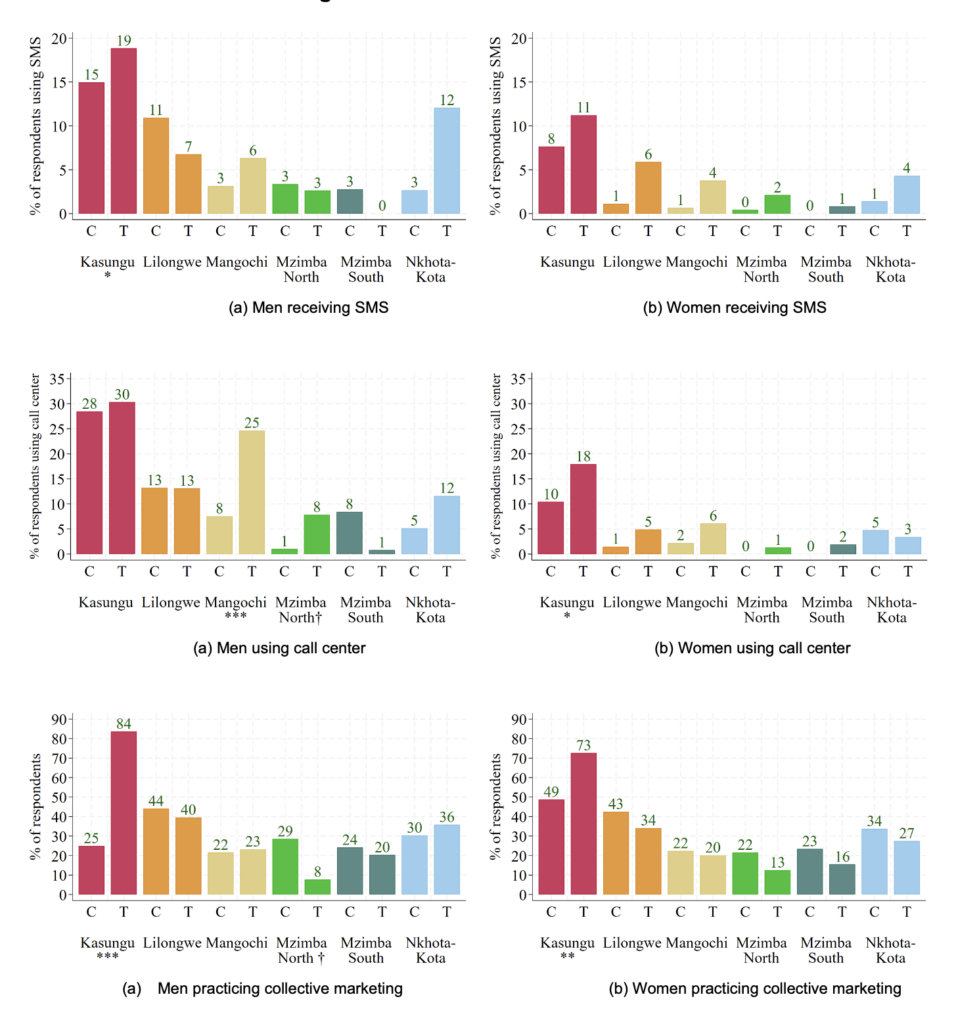

2. Improved awareness and use of digital tools and promoted approaches. More farmers in treatment groups in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota received SMS, used the call center, and practiced collective marketing, which led to greater crop income increases in these districts (Figure 2). Coverage and reach to intended beneficiaries remain very low in the other three focus districts, which explains the limited impact achieved there.

Figure 2: Greater access to SMS and call center and collective marketing contribute to crop income increase in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota

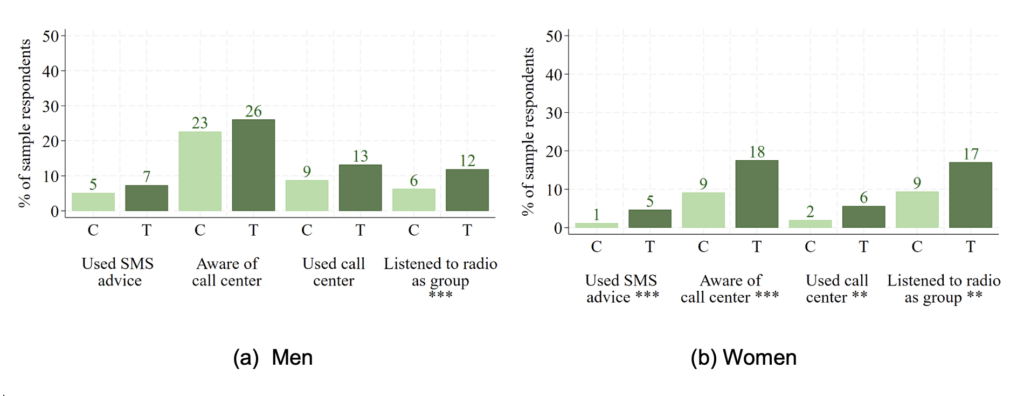

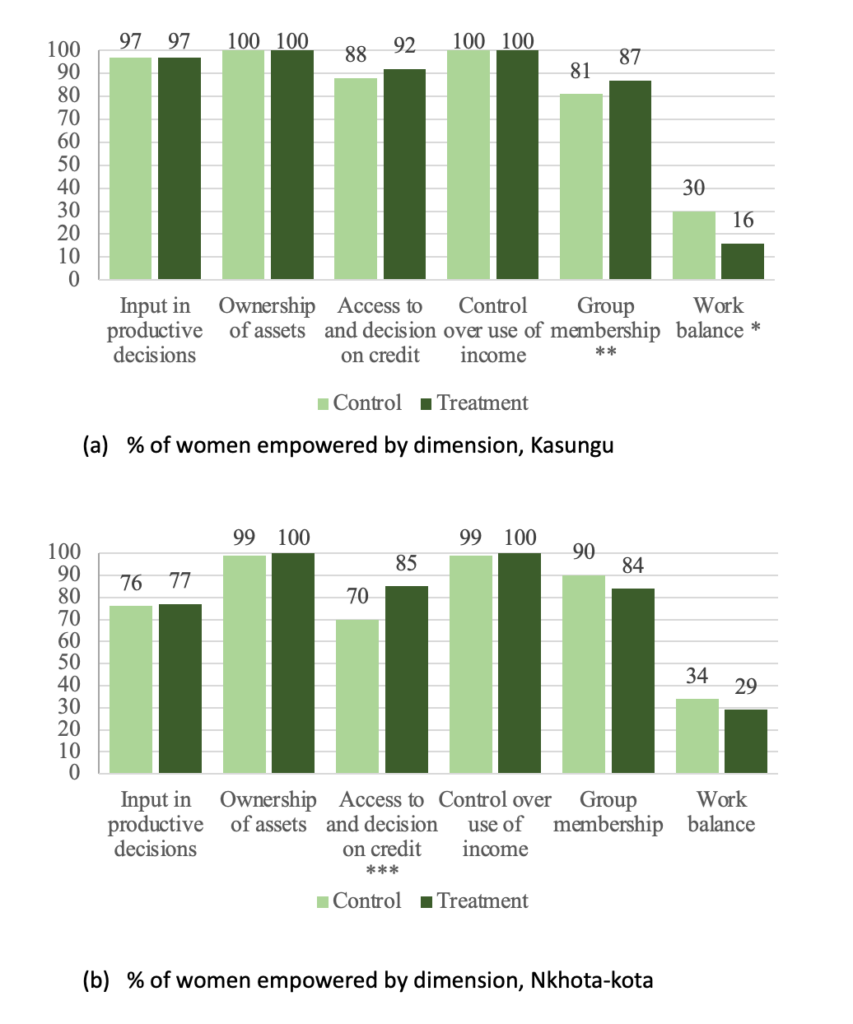

3. Reduced gender gap and greater women’s empowerment. Compared to control groups, women in the treatment groups have greater receipt of SMS, call center use, and participation in radio listening clubs, with gender gaps narrowing in those indicators because of efforts to reach women in households and groups (Figure 3). While there is no overall impact on women’s empowerment, disaggregating by dimension and district shows that women’s group membership improved in Kasungu and women’s access to and control over financial resources improved in Nkhota-kota (Figure 4). However, work balance may have decreased and workload may have increased for women, and this needs to be monitored closely.

Figure 3. More women were able to access digital tools and group-based approaches

Figure 4. Gender indicators

Outcomes showing no impact and areas for improvement

1. Limited access to digital technologies. Although 67% of sample group members have cell phones, only 17% have smartphones, presenting a major barrier to watching videos. In a few groups, less than 20% of members have cell phone access. This limits the ability to reach all members of the ICT hubs, and suggests the necessity of combining traditional and more advanced digital tools for wider inclusion and benefits.

2. Slow implementation and low coverage. As shown in Figure 3, only 8% of men and 5% of women in treatment groups received SMS on agriculture, health, or markets; 13% of men and 6% of women used the call center/hotline; and 12% of men and 17% of women participated in radio listening groups. More intensive and wider implementation of these interventions in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota are leading to positive impacts in crop incomes there. Slower implementation and very low coverage in the other districts explain limited impact in those districts.

3. Low adoption of promoted management practices. Tracking and comparing awareness and adoption of 48 agricultural management, marketing, and nutrition practices, we find significant improvement in marketing practices in Kasungu and to some extent in Nkhota-kota, but limited improvement in the production and livestock management practices that farmers adopt. Notable improvements in a few management practices include herbicide use, manure use, and soil testing in Kasungu; and herbicide use, rice intensification, maize-legume intercropping/rotation in Nkhota-kota. No notable improvement in management practices observed in other focus districts.

4. Limited improvement in productivity and dietary diversity. The interventions have not yet led to improved productivity in maize and other crops or to overall dietary diversity. There are small increases in crop productivity in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota but not in other districts. There are also small impacts on dietary diversity in Kasungu, Mangochi, and Nkhota-kota, although inconsistent across estimations.

Recommendations for programming

As Farm Radio Trust continues the implementation of the ICT hub interventions, we recommend these 10 points to improve the program based on our study findings. These can also provide lessons for other organizations implementing similar ICT interventions in Malawi.

1. Update phone numbers for SMS push. Phone listings for participants must be completed and regularly updated since people change cellphones and group membership also changes. The program should aim to cover all group members and intended beneficiaries who have cellphones and also include household members who have cellphone numbers. This will expand coverage and make the service provision more inclusive without extra costs.

2. Fix call center issues. While many farmers find calling the call center useful, some farmers said nobody answered when they called. These issues need to be fixed to ensure that farmers get timely and useful advice on their farming and marketing. In addition, many farmers were not aware of the call center; greater promotion through SMS and radio programs will be needed.

3. Implement group-based video screening. Videos would have been a good complementary tool, but were the slowest to be implemented. Instead of individual screening or screening through the ICT champions, group-based video screening should be implemented to increase the reach to all members without smartphones.

4. Providing SMS and videos in multiple languages. SMS and videos are currently provided in Chichewa language but Mzimba, one of the focus districts use Tumbuka more, and some of its communities use Yao language SMS and videos need to accommodate the diverse linguistic preferences of the intended beneficiaries.

5. Combine complementary ICT tools. Many farmers considered SMS and call center promotion useful, and these have contributed to improved crop income in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota. These interventions should be expanded. SMS and call center assistance are highly complementary and can be promoted and scaled to other producer groups in Malawi. SMS texts promote using the call center; and call center offerings can help expand the use of SMS texts and availability of advice to farmers. Collective marketing, which is a main contributor of improved crop incomes in Kasungu and Nkhota-kota, was promoted via SMS and call center. Videos were considered useful, and can be used to complement, illustrate, and visualize complex management practices being promoted through SMS texts and call center use.

6. Continue and expand radio programs. Farmers in Malawi often listen to radio programs, which are a major source of agricultural information among treatment and control groups. Such programming must be continued and expanded. It complemented the SMS and call center messages and is the major source of agricultural information for those without cellphone access. Agricultural radio programs should be expanded. Farmers recommended forming training groups to fix radios that would also pitch in for radio replacement, and suggested incorporating dramas into radio programs for communicating agricultural information.

7. Strengthen facilitation and expand participation in radio listening clubs. Compared to SMS and call center use, radio listening clubs are not correlated to crop income or productivity improvements. These clubs were relatively popular among women but were not popular among men. They should be promoted and facilitated further to reach both genders, and include and improve discussions on pressing agricultural management and marketing issues farmers’ face and their solutions.

8. Expand targeting of women farmers. Building on the early positive gender impacts of the interventions, the program should aim to reach more women members of groups and households, However, women’s workloads should be closely monitored to ensure that interventions do not lead to time burden and disempowerment.

9. Improve technology adoption, productivity, and dietary diversity. The program should expand its coverage and service provision to more beneficiaries. Increased promotion can help to improve adoption of management practices, particularly productivity-enhancing and resilient agricultural practices and livestock management practices.

10. Accelerate impact on market access and income. To enhance the positive outcomes in crop income, we suggest expanding collective marketing support and promoting diversification into higher value crops such as soya, groundnuts, rice, and some fruits, particularly in districts where crop income has not increased.

The program is set to continue and the intervention bundle is set to expand to more ICT hubs until 2025, building on the lessons from this midline evaluation. It will be important to continue to monitor and evaluate the development impacts of the ICT hubs and the whole program by 2025.

Catherine Ragasa is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling (IPS) Unit; Ning Ma is an IPS Research Analyst; Emmanuel Hami is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance Unit, based in Lilongwe, Malawi. This post is based on research that is not yet peer reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

Support for this research was provided by the Government of Flanders.