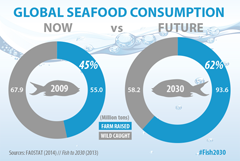

Amid a future of growing populations, economies, and changing diets, questions arise as to how current practices can meet future food demands. Aquaculture, also known as fish farming, may be key: It is expected that as much as two-thirds of all fish consumed will come from aquaculture by 2030.

Fish to 2030: Prospects for Fisheries and Aquaculture, a joint report of the World Bank, the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), provides projections on global fish production, consumption, and trade into 2030 using modeling to construct different scenarios in global fish markets. The report focuses on three themes: the health of global wild fish populations, the role of aquaculture in meeting global demand, and the implications of changes in global fish markets on fish consumption, in both developed and the developing regions.

Using an extension of IFPRI’s IMPACT Model, projections were generated under different assumptions about drivers of the global fish markets. According to the report, total fish supply will increase from 154 million tons in 2011 to 186 million tons in 2030, and aquaculture’s share of global fish supply will continue to expand to the point where capture fisheries and aquaculture will be contributing equal amounts by 2030. Siwa Msangi, a senior research fellow at IFPRI and the lead author of the study, said “Comparing this study to the results of the earlier 2003 study by IFPRI and WorldFish, we can see that growth in aquaculture production has been much stronger than what we thought. The projected 2020 production levels were already realized by 2010, whereas capture production, by contrast, grew far less than what was envisioned. The incredibly dynamic nature of the aquaculture sector makes it a difficult – but also exciting – sector to model.”

Such findings beg the question: Given aquaculture’s continued projected growth, how will this change the prices and consumption patterns in global seafood markets?

According to FAO data, more than two-thirds of current fishery exports (in value terms) by developing countries are exported to developed countries. The report identifies Asia—and China in particular—as a major source and driver of the growing global demand for fish, owing largely to a burgeoning middle class. Overall, the region is projected to account for 70 percent of global fish consumption by 2030, with China alone accounting for 38 percent. Africa south of the Sahara, on the other hand, is predicted to see an annual 1-percent decline in per capita fish consumption until 2030, though overall consumption rates are expected to increase by up to 30 percent due to rapid population growth throughout the region.

The report identifies the rapidly growing aquaculture sector as a means of meeting rising global demand for fish. An estimated 62 percent of food fish will come from farm-raised sources by 2030, an 18 percent increase from current consumption patterns. The fastest supply growth is likely to be derived from tilapia, carp, and catfish farming, with tilapia production expected to nearly double from 4.3 million tons to 7.3 million tons between 2010 and 2030.

Yet the prospect of a rapidly growing aquaculture supply is not without significant risk, caution the report’s authors. At the launch of the book, Juergen Voegel, the World Bank’s director of Agriculture and Environmental Services, underscored the importance of developing countries implementing proper policy frameworks before diving into large-scale aquaculture to minimize risk to the environment and human health. “Supplying fish sustainably—producing it without depleting productive natural resources and without damaging the precious aquatic environment—is a huge challenge. We continue to see excessive and irresponsible harvesting in capture fisheries and in aquaculture, disease outbreaks among other things, have heavily impacted production. If countries can get their resource management right, they will be placed to benefit from the changing trade environment.”

IFPRI’s Siwa Msangi said the report also highlights the ways in which aquaculture is indispensable to meeting the future demand for seafood and contributing to the supply of animal-based protein. Given that so much of the quantitative effort went into preparing the data, this study also underscores the need for better information on fish—in terms of prices and the harmonization of supply, demand, and trade information. In truth, one of the biggest values of the modeling was to provide an internally consistent framework in which to reconcile the data, challenge assumptions, and explore possibilities through scenarios. “We will continue to build on this framework as we explore further how policy improvements, technological innovations, and future socio-economic and environmental change will shape the future of seafood markets to 2030 and beyond,” he said.

Related materials: