Part of a series on key themes of IFPRI’s 2024 Global Food Policy Report.

Enhancing access to affordable, healthy, and diverse diets is an important and growing policy priority around the world as many countries face public health problems of malnutrition and diet-related non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, as well as challenges from climate change, conflict, and other stresses on food systems. But expanding access to nutritious foods is impossible to achieve without at the same time strengthening institutions and relationships across public, private and civil society partners. With World Food Day 2024 (October 16) approaching, this challenge is more urgent than ever.

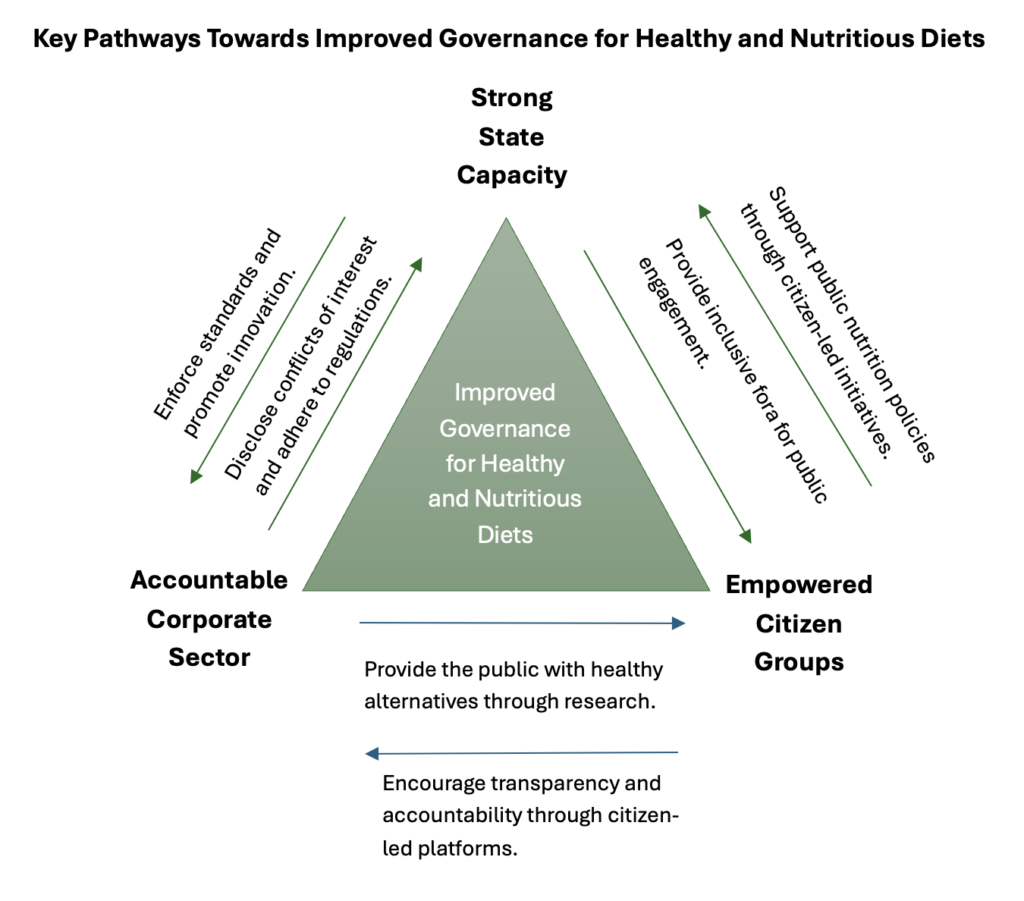

This key issue of better governance is highlighted in Chapter 8 of IFPRI’s 2024 Global Food Policy Report, with an emphasis on three dimensions critical for bolstering diets and nutrition: Strengthening state capacities, improving corporate accountability, and fostering citizen agency in decisions about healthy foods. As seen in Figure 1 below, these three dimensions also interact with each other, ideally creating important positive feedback loops affecting all aspects of food system transformation.

Figure 1

Enhancing state capacity

State capacity is fundamental to implementing and sustaining policies for diets and nutrition. This refers to a government’s ability to formulate policy, regulate commercial activities, deliver services, navigate trade-offs across different objectives, and extract revenue in accountable ways.

For instance, targeting households that would most benefit from subsidies on healthy foods requires a high level of technical competence and record-keeping, while the design of food industry regulations requires investment in oversight and enforcement capabilities. Capacity is also required to foster coordination between nutrition goals and other state priorities, as seen in countries like Nigeria and South Africa that are trying to implement sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes to reduce consumption and improve nutrition while simultaneously protecting jobs in their sugar industries.

Given that policy efficacy varies over time, capacity also involves learning and adaptation, especially as new data and standards emerge. For instance, while SSB taxes were widely adopted in Latin America through the 2010s, it was found that they alone were not sufficient to tackle obesity, and their impact erodes if they are not benchmarked to inflation. Consequently, Chile supplemented its SSB tax regime with the adoption of a comprehensive law in 2016 to mandate restrictions on marketing ultra-processed foods to children and requiring front-of-package labeling for foods high in sugar, salt, and transfats. Similarly, after almost two decades of large-scale food fortification (LSFF) policies in LMICs, researchers have found that such programs are most effective when accompanied by sustainability planning, including continuous quality assurance and control, monitoring of industrial processors, and corrective measures as consumption patterns change over time in a country.

Navigating corporate influence

Of course, the public sector cannot enhance diets and nutrition alone, and the private sector is a key player to help governments achieve their goals. On the one hand, governments have sometimes been co-opted by the corporate food industry and especially by “Big Food” companies that promote ultra processed products. Several studies reveal how multinational food companies influence policy decisions through corporate spending to affect electoral outcomes, biasing scientific studies, and lobbying to persuade legislators. In fact, by constructing a Corporate Financial Influence Index, researchers have found that the implementation of polices recommended by the World Health Organization to address non-communicable diseases has been lower where corporate influence is higher.

On the other hand, in most countries the private sector has diverse actors with disparate motivations and goals. Indeed, some businesses play a more positive role by addressing malnutrition and encouraging healthy diets. For instance, TAF foods, a large-scale food manufacturer in Madagascar, partnered with civil society organizations to provide fortified infant flour at an affordable price.

Elsewhere, the food industry plays an important role in exploring new food sources such as plant- and insect-based alternative proteins, increasing access to fresh food, and encouraging positive consumer choices through voluntary disclosures. Increasingly, corporate actors also are embracing transparency initiatives, such as the Zero Hunger Pledge, whereby companies declare their commitment to ending world hunger and promoting nutrition, and the micronutrient fortification index in Nigeria where companies annually publish their progress with fortifying edible oils and wheat flour with critical vitamins.

Fostering citizen agency

Enhancing citizen agency—creating opportunities for individuals to exercise their voice in decision-making structures—can facilitate greater accountability of both governments and the corporate sector to support healthy food systems. In recent years, citizen agency has been recognized as a pivotal dimension of food security by the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. An important example is the emergence of citizen-led initiatives like food policy roundtables and the establishment of multistakeholder food platforms bringing together civil society groups with public sector representatives and members of the business community.

An additional benefit of some of these initiatives, such as the now decade-old La Paz Food Security Committee in Bolivia, is that they not only identify options to improve healthy diets but also further bolster local communities to address other food-related issues, such as food loss and waste. Performance tracking initiatives, such as the Food and Agriculture Corporate Transparency (FACT) index, that monitor the degree of political influence major food corporations exert on decision-makers, are another way that civil society is providing oversight.

Yet such efforts often face obstacles, as they depend heavily on the existence of freedom of expression and association. Unfortunately, these rights have become more constrained globally over the last decade, affecting groups that advocate for rights to food. Moreover, multistakeholder platforms have sometimes been accused of power asymmetries in composition or interest articulation, potentially translating into inequalities within the food system, which suggests the need for in-built and frequent mechanisms of self-reflection among members.

Pathways for improved governance

Numerous policy levers exist to enhance access to affordable, healthy, and diverse diets—including subsidies for healthy foods, taxes on unhealthy ones, and regulations to ensure laws on labeling and advertising are respected. Yet adopting and implementing such policies requires effective governance, and the enabling governance conditions—across public, private, and civil society stakeholders as well as between national and subnational scales—vary significantly.

Adopting a governance perspective and broadly improving these conditions allows for a more comprehensive action agenda for diets and nutrition. Based on the discussion above and further details provided in the GFPR, specific recommendations to do so include the following:

- Complement health and economic analyses of policy options for healthy diets with governance assessments to ensure desired interventions are actually sustainable and scalable.

- Identify and address binding governance constraints on implementing policies for healthy diets and nutrition—which may include insufficient funding, data opacity and corruption, and demoralization among frontline service providers—in order to expand politically feasible policy options for improving nutrition.

- Enhance equitable access to information to foster better accountability for food systems, utilizing tools like transparency scorecards and monitoring public and private sector commitments to nutrition goals.

- Encourage and support the expansion of civic space to enable grassroots input into debates about needed policy options to achieve healthy food systems.

Looking forward, achieving better diets and nutrition will require investing in not only better data and analysis about the consumption behaviors, food environments, and economic circumstances of specific population groups, but also identifying how to calibrate promising policy interventions to a country’s unique governance environment.

Danielle Resnick is a Senior Research Fellow in IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Brookings Institution; Aditi Chugh is a DSG Research Analyst.