Note: A modified version of this story originally appeared on Dani Rodrik’s weblog on March 28, 2014.

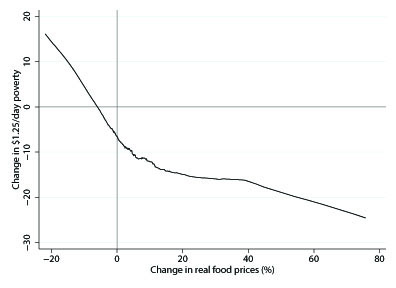

Since the poor spend a greater share of their household incomes on purchasing food, higher food prices must exacerbate poverty, right? Wrong . . . at least over the medium term. In my most recent paper, I find that the opposite is true: higher domestic food prices predict reductions in poverty. The methods in this paper are fairly simple. I take World Bank national poverty estimates for a broad swathe of countries and regress changes in poverty against changes in domestic food prices (the ratio of the food CPI to the non-food CPI). The main finding is that the elasticity between $1.25 poverty and food prices varies between -0.32 and -0.46 (see Figure below). The result is also a robust one in that it holds for different models, different regressors, different assumptions about the endogeneity of food prices, and different poverty indicators.

There are two important caveats to this result, however. The first is that we don’t know exactly why this relationship exists, though the most compelling hypothesis is that higher food prices trigger large wage adjustments, at least in the long run. A recent World Bank working paper by Hanan Jacoby persuasively demonstrates this in a simple general equilibrium model for rural India (see here). Thus, even if many poor people are net food consumers, the fact that they are large net sellers of labor means that they can ultimately benefit wage increases induced by higher food prices.

The second caveat is that this is a “long run” relationship, in the economic sense of the term, meaning “after all adjustments have taken place”. How long is this adjustment in practice? We don’t really know. There’s a great scarcity of research on wages and food prices, and almost all of it comes from Bangladesh and is now rather dated (e.g. Ravallion 1990). In my sample of poverty episodes, however, I show that the negative poverty-food prices elasticities reported above even hold for episodes as short as 2 years. This suggests that the long run may not be very long. At the same time, one cannot rule out negative welfare impacts of higher food prices in the short run, which would still imply an important role for social protection, and perhaps also for price stabilization measures. Over the longer term, however, higher food prices typically seem to be a boon for poverty reduction.

Related materials