Gender and equity are cross-cutting themes across the five flagship programs of the CGIAR’s Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH). In this interview with A4NH’s Elena Martinez, Dr. Kathryn Yount, Professor and Asa Griggs Candler Chair of Global Health at Emory University and member of the External Advisory Committee of IFPRI’s Gender, Agriculture, and Assets Project Phase Two (GAAP2), discusses how to conceptualize and measure the process of women’s empowerment and why this issue is important for development work.

A4NH: Empowerment is a multidimensional and complex idea. How do you conceptualize women’s empowerment?

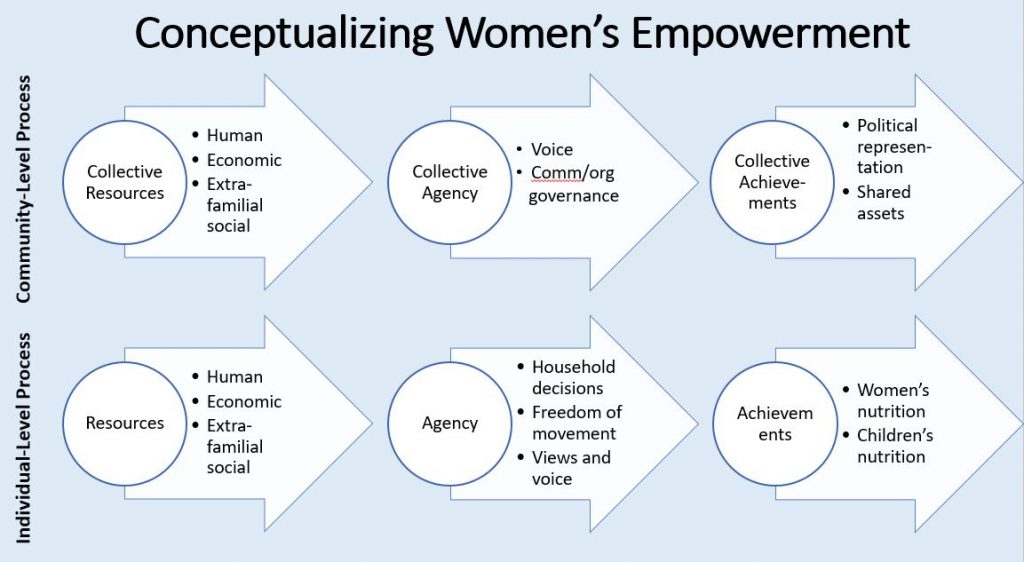

Yount: I conceptualize women’s empowerment based on a framework developed by Naila Kabeer (1999). This framework depicts empowerment as a dynamic process, in which women acquire resources that enable them to develop voice (the capacity to articulate preferences) and agency (the capacity to make decisions) to fulfill their own aspirations. These resources include human resources such as schooling attainment, skill development, and self-efficacy; social resources such as participation in organizations, access to peer networks, and access to role models outside the family; and economic resources or material assets such as earnings, property, and land.

Kathryn Yount

Resources enable but do not necessarily guarantee empowerment because of the broader structural and normative environment in which girls grow up. From a theoretical point of view, a women’s ability to become empowered at the individual level depends on the environment in which she lives. If she is living in a very disempowered community, it will be difficult for her to gain access to the resources to develop voice and agency. So, it is important for communities to evolve with respect to the opportunities for women, norms about gender, and women’s collective voice and agency. However, researchers have yet not done a good job of conceptualizing and measuring empowerment at the community level and of evaluating the impacts of multilevel empowerment programs.

A4NH: Is there a difference between women’s empowerment at the individual and community levels? How do you measure them?

Yount: Drawing on Kabeer’s framework, we measure women’s access to enabling human, social, and economic resources. These indicators include things like school attainment, access to training programs and informal skills building opportunities, and engagement with solidarity groups, among others. We measure women’s agency and voice through indicators including women’s influence and participation in decisions at the household and expanded family levels, women’s attitudes about gender, women’s willingness to voice attitudes that differ from the norm in the community, husbands’ control over women, and women’s ability to move freely in public and private spaces.

The factors that matter for empowerment at the individual and community levels may not be the same. The next step for developing measures of empowerment is to compare what is relevant at the individual and community levels, which has not been done yet on any wide scale. My research group at Emory has been especially interested in measures of women’s collective efficacy—the extent to which women have formed peer networks that they believe in, trust, and rely on in cases of need. We also have looked at disparities in schooling attainment and workforce opportunities, as well as norms about gender and violence against women in the community. In observational studies, these norms have been strongly related to a range of women’s health outcomes, particularly their risk of experiencing intimate partner violence.

A4NH: What are the challenges of measuring women’s empowerment?

Yount: Measures of empowerment have proliferated without being systematically evaluated across contexts and over time. On the one hand, from a theoretical point of view, women’s empowerment is multidimensional and context-specific. On the other hand, similar measures have been developed for use across contexts. So, rigorous testing of the invariance of these measures across contexts and over time is critical. I have been advocating for the development of questionnaires that allow for comparative but also intensive, context-specific measurement of women’s empowerment. Some items may work well in some contexts but not in others, and other items may work well across many contexts and survey years. Also, measuring women’s empowerment is challenging because it often requires long, involved scales to measure multiple dimensions. For program monitoring, we need to pare these measures down to a core set so the process of measuring women’s empowerment is not onerous over time for program staff.

A4NH: Why is measuring women’s empowerment important in development work?

Yount: Measuring women’s empowerment is important because it provides a regular reminder of its importance to staff and programs. There are many agricultural development programs that do not have a gender or empowerment focus, but by having measures of women’s empowerment embedded in their monitoring systems, staff members are encouraged to consider women’s empowerment as a goal for the project. It also is important to train staff members on existing inequities, gender and other social equities, and how empowerment processes can work to enhance equity. Also critical are the norm change implications of having women’s empowerment measures embedded in program monitoring. Engaging program staff, program beneficiaries, and communities more broadly on questions of empowerment raises awareness on these issues and thereby helps to encourage social norm change.

This post first appeared on the A4NH Gender-Nutrition Idea Exchange Blog.