Forests are massive carbon sinks and biodiversity havens. The world’s forests store about 861 gigatons of carbon, 42% in live biomass and 44% in soil. Yet forest areas have been disappearing at an alarming rate: Globally, they have shrunk by 20% over the past 100 years, mostly due to expansion of agricultural lands. Given the urgency of reducing global CO2 emissions, world leaders at the 2021 COP26 Global Climate Conference in Glasgow made a non-binding declaration to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. This pledge, endorsed by 145 countries covering 91% of the world’s forests, was hailed as a significant step toward stopping global deforestation.

To understand the potential impact of the declaration, researchers from IFPRI and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) used an open-source land-use modeling framework—the Model of Agricultural Production and its Impact on the Environment (MAgPIE)—to examine its global effects on land use.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters, shows that an all-out effort to meet the pledge would have complex impacts on other forms of land use—suggesting that broad efforts to limit deforestation should be managed in a wider context. The results show that employing integrated land-use perspectives is essential for reducing deforestation within climate change mitigation policy and in managing competition for land.

Unintended pitfalls

Two scenarios were set up to model the potential impacts of the COP26 declaration: 1) a baseline deforestation scenario following the “Middle of the Road” Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP2), and 2) a COP26 scenario in which global policy to halt agriculture-driven deforestation was assumed to be immediately ramped up by all participating countries and fully achieved by 2030.

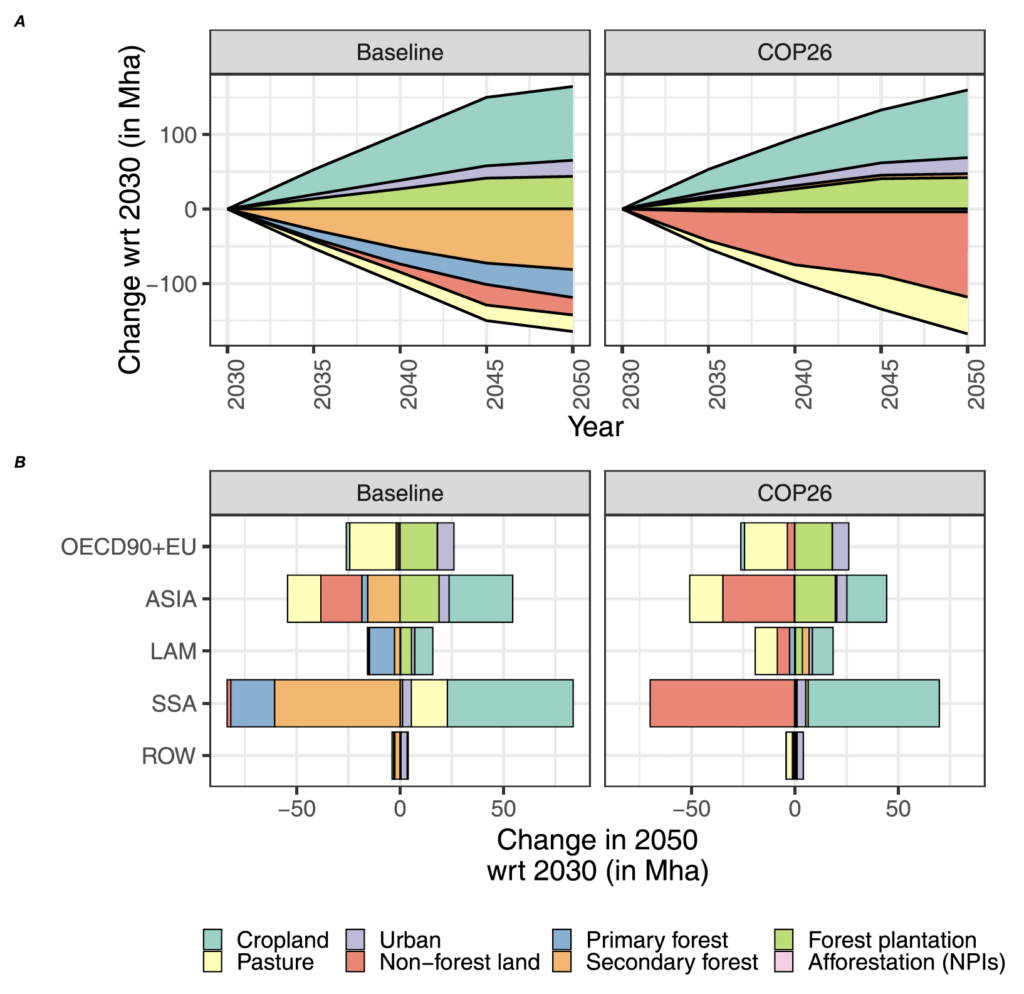

The analysis found that under the latter, full-implementation scenario, about 167 million hectares of deforestation could be avoided until 2050, compared to the baseline scenario with no extended action to limit agriculture-driven deforestation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Land-use change of major land types over time compared to 2030 for two scenarios

However, that avoided deforestation and associated reduced emissions would come at the cost of strongly increased conversion of unprotected non-forested land to agricultural land, the analysis suggests.

While avoided deforestation leads to a reduction in CO2 emissions in the model, the land-use change dynamics remain a zero-sum game: Protecting one class of land (forests) results in higher pressure on other forms of land use, with agricultural activities intensifying in existing farming regions and/or expanding into non-protected areas. Thus, while it might be possible to save forestlands from agriculture-driven deforestation under the COP26 declaration, the rising global pressure to produce food would result in spillover effects.

The study highlights a critical set of trade-offs: How best to manage forest protection when it can inadvertently push deforestation pressures onto other types of land.

The COP26 scenario might offer opportunities to address this problem by building on synergies between agricultural production and restoration/reforestation—e.g., forms of agroforestry.

Yet the effects of dramatically scaling up forest protection under the COP26 scenario are complex. With many forests placed legally off-limits, agricultural expansion would likely shift to remaining unprotected forests and non-forest areas, modeling indicates. For example, vast swaths of non-forested land, including grasslands and other areas, could be converted into farmland, which would then release significant amounts of CO2. Such expansion of agricultural areas could also further reduce the land area available for restoration/reforestation—indirectly leading to a conflict with climate change mitigation.

Comprehensive policies needed for real impact

This research underscores the policy challenges of managing complex land-use dynamics. The stylized example of fulfilling the COP26 declaration in the next six years is far off from the on-the-ground realities of today’s world. The non-binding declaration has no global enforcement mechanism, yet also calls for safeguarding unprotected non-forest lands, promoting sustainable agricultural practices, and ensuring food security—each a tremendous challenge in its own right. In addition, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for reducing carbon emissions established by the Paris Climate Agreement do not foresee the potential displacement effects of forest conservation to other land uses, especially for agriculture.

This study highlights the importance of employing integrated land-use perspectives for reducing deforestation as a climate change mitigation policy and in managing competition for land. This research could be used by Paris Agreement signatories for updating their NDC formulations—addressing potential increases in carbon emissions and losses in biodiversity due to the loss of non-forested areas under a COP26-like global forest protection policy.

Efforts to reduce deforestation, especially via NDCs, have lately been gaining international currency. Legislative initiatives in some of the leading global economies, including the European Union’s Regulation on Deforestation-free Products, the United Kingdom’s Environment Act, and China’s Forest Law show that some progress has been made in codifying the right steps to avoid (agriculture-driven) deforestation.

However, this trend is hardly universal. For example, a bill to combat illegal deforestation by prohibiting the importation of products produced on land undergoing illegal deforestation has thus far failed to pass the U.S. Congress. Thus, we believe it is crucial to keep building on the current global momentum for policies to stop deforestation, and to urge policymakers to incorporate a holistic perspective on land use.

The COP26 declaration, though non-binding, is a commendable step toward protecting our planet’s forests. However, our study indicates that solutions to complex problems like deforestation and climate change are rarely straightforward. While halting deforestation is crucial, we must also anticipate and address potential side effects such as accelerated conversion of unprotected non-forest lands. The goal should be to create a sustainable future in which global resources including both forests and non-forest lands are protected, ensuring that we do not simply shift environmental degradation from one area to another.

Abhijeet Mishra is an Associate Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Foresight and Policy Modeling (FPM) Unit and a Guest Scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Eleanor Jones is an FPM Program Manager.

Support for this research was provided by the CGIAR Research Initiative on Foresight.

Referenced paper:

Mishra, A., Humpenöder, F., Reyer, C. P., Beier, F., Lotze-Campen, H., & Popp, A. (2024). Emission savings through the COP26 declaration of deforestation could come at the expense of non-forest land conversion. Environmental Research Letters, 19(5), 054058. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad42b4