Control of epidemic diseases relies on public compliance with government decisions and scientific advice. What does trust have to do with it? According to Danielle Resnick, a lot: Changing the behavior of citizens depends upon it. She highlights multiple gaps in trust in different pandemic responses around the world, and outlines the factors underlying them—and offers insights into how politicians and scientists might build the trust needed in leading ongoing mitigation responses to COVID-19 and resilience to future epidemics.—John McDermott, series co-editor and Director, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

In mid-April, Tanzania’s prime minister made a simple plea: “Tanzanians should maintain trust in the government. You should continue to trust our experts who are behind every decision we make.” A month later, the country’s president fired the head of its national COVID-19 test laboratory and committed to importing an untested herbal tonic from Madagascar that has been controversially touted as a cure to the novel coronavirus despite scientists’ worries it could lead to drug-resistant malaria.

Protecting public health in a pandemic depends on citizens’ trust in government decisions, and on political leaders’ trust in the findings of the scientific community. But as the Tanzania example shows, such trust can be fragile. Breakdowns at these two junctures explain some of the disparate policy responses to COVID-19 and varying citizen compliance around the world. Where and when it occurs, this erosion of trust can put lives at risk and have broad implications for the flow of accurate information and accountability. Now, as governments begin lifting lockdown orders and gradually re-opening, recognizing this problem and rebuilding trust is critical.

What’s trust got to do with it?

Trust is a complex phenomenon. Trust in political institutions refers to citizens’ relative confidence that their governments are capable, reliable, impartial, and efficient, and is often shaped by partisanship, access to news, and past interactions with government authorities. It can be influenced by expectations of what one’s government should be doing, given its capacities, rather than on a universally accepted notion of good governance or objective performance metrics. Such trust is critical for state legitimacy and can be associated with willingness to pay taxes, respect for property rights, and following the rule of law.

The stresses of COVID-19 have put trust in government to the test in many places—and shown how weak it can be. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) has identified more than 4,000 episodes of violence associated with COVID-19-related restrictions since March, with protests and riots by citizens and under-protected healthcare workers a common outcome in many countries. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) has already warned that if people lack trust in their government’s responses, there is even a greater risk of violent outbreaks in that region.

Trust in science, meanwhile, reflects people’s confidence in a cumulative body of research findings derived from a process of data collection, hypothesis testing, and peer review. Such confidence determines whether citizens are willing to change their individual behaviors to promote outcomes that benefit the greater societal good.

Public distrust in science has undermined more concerted international collaboration on climate change, created skepticism about nutritious diets, and discouraged community cooperation during other public health emergencies, from measles in the United States to Ebola in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Such distrust can be the product of both individuals’ own backgrounds as well as mixed messages by researchers, including on the utility of face masks in the current pandemic. And such mixed messages are more likely in crisis periods when the pressure to publish results quickly is particularly intense.

When we consider these two sources of distrust in tandem, two distinct clusters of policy responses to COVID-19 emerge. On the one hand, governments in some highly polarized environments disparage scientific recommendations. On the other hand, in some countries segments of the public may believe that the advice of scientific experts is being manipulated to advance political gains.

Populism and polarization

Some of the most muddled responses have occurred in countries that have experienced growing political polarization fueled by a resurgence of both right- and left-wing populism in recent years, including Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, the Philippines, and the U.S., among others. Populist leaders thrive on unmediated contact with the people they claim to represent and disdain formal institutions, including international bodies like the World Health Organization, that threaten their political maneuvering room. Across the ideological spectrum, these leaders have staked their credibility on promises of improved economic opportunities for the forgotten masses—a goal imperiled by shutdowns and business restrictions. Questioning the legitimacy of the rapidly-evolving scientific understanding of COVID-19 becomes a convenient pretext for delaying or reversing actions with economic consequences.

One of the most obstinate has been Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who dismissed the pandemic as “hysteria,” claimed infection rates were inflated, ignored social distancing guidelines when meeting with supporters, and halted the public release of national COVID-19 statistics. Despite alarms raised by Nicaraguan doctors, Nicaragua’s husband and wife populist leaders, President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo, called for a “Love in the Time of COVID-19” mass parade in mid-March and a marathon and food festival a few weeks later. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte called worriers about the novel coronavirus “fools” and violated a “no touch” policy (meaning no one should touch him at public events), hugging and shaking hands with supporters.

Fear of abuse of power and political pandering

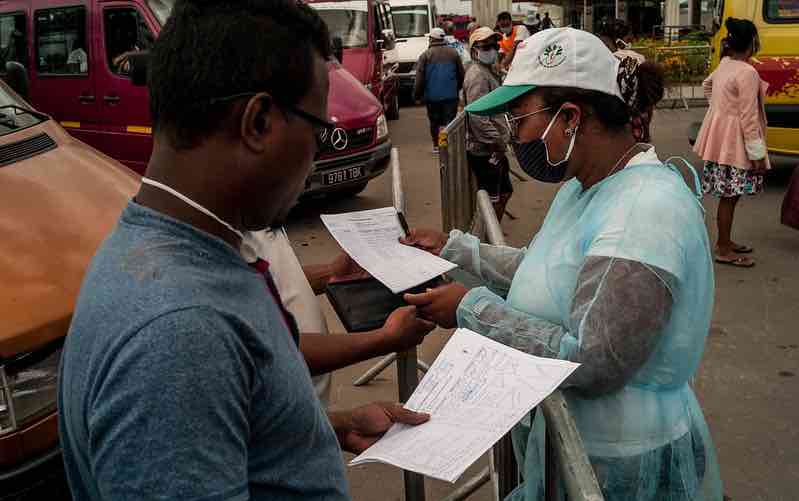

In a number of other countries, pandemic advice from the scientific community is not being questioned as intensely, but political distrust is raising skepticism about the motivations underlying governments’ policy responses. Some of this is due to previous abuses of power by leaders who are now invoking states of emergency to respond to the pandemic. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s ability to rule by decree is a clear example, as his government uses pandemic legislation to undermine gender rights and freedom of the press. In Latin America and Africa, there are concerns that the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions has led to excessive use of police and military force. For some of Africa’s urban poor, including those living in slums and working in informal trade, authorities’ use of violence to enforce social distancing and lockdowns can only further erode confidence in the state. For instance, in Harare, long a stronghold for Zimbabwe’s political opposition, state authorities have destroyed stalls and merchandise in multiple open-air markets; while in Uganda, police have beaten traders who showed up at markets that were closed.

Skepticism toward COVID-19 policies is also pronounced in countries where elections are on the horizon. On April 17, across may cities of Malawi, informal traders marched in protest over planned lockdowns by President Peter Mutharika that were subsequently challenged in the High Court. In the wake of a rigged 2019 presidential election scheduled to be re-run in July, trust in the ruling regime is low, symbolized by an unprecedent level of protests in the country in 2020, and concerns about the politicization of the lockdown have been high. In neighboring Zambia, where the incumbent ruling party also faces a competitive race next year, some masks distributed to the public have been branded with the ruling Patriotic Front’s label.

Misinformation and muddled accountability

Where there is distrust in either government or science, the flow of credible information and accountability are at risk. Some of the world’s more illiberal regimes have sought to limit media dissemination of scientific information about COVID-19 where it could be seen as sowing doubts about their performance to contain the pandemic. In the Philippines, for example, Duterte has shut down one of the main media broadcasters. Similarly, in May the government of Zambia revoked the broadcasting license of one of the country’s few independent television stations.

In settings where many citizens have low levels of literacy and education, misinformation can have dangerous implications. In India and Mexico, numerous healthcare workers have been physically attacked in the mistaken belief that they carry the coronavirus, and in Côte d’Ivoire, protesters ransacked a COVID-19 testing facility. At the same time, there are leaders who continue to espouse dangerous and unproven theories of COVID-19 cures, including Madagascar President Andry Rajoelina, who has promoted the tonic embraced by Tanzania’s president, and Nairobi Governor Mike Sonko, who has advocated for greater consumption of cognac. The independent website Africa Check has documented dozens of untruths about coronavirus cures circulating in the region. Such measures make people more complacent about taking health precautions, as they gamble on a cure with no scientific credibility—and the remedies themselves can be extremely dangerous, as shown by cases of chloroquine poisoning in Lagos after that was touted as a cure.

Whom can you trust?

Distrust in national-level authorities in some countries leaves a critical void that imperils efforts to contain COVID-19 and restart moribund economies. However, there are often other actors who retain high levels of public trust and who are being called upon to disseminate essential information for protecting public health. In some settings, local authorities are viewed as more trustworthy because they live and work in closer proximity to their constituents—and therefore exercise greater oversight and accountability. In East Asia, this dynamic is particularly strong in democratic regimes, while in Europe, local trust is greater in more decentralized systems. For more than a decade, public opinion surveys have shown that local government in the U.S. has been trusted more than state or federal government, and a similar pattern emerges regarding trust in handling the coronavirus.

The Africa CDC advocates that authorities steer away from implementing uniform national public health and social measures and instead tailor interventions to local needs based on feedback with community leaders. This reflects public opinion surveys from Afrobarometer consistently finding that trust in community leaders, such as religious and traditional authorities, is higher than that for formal state agencies in Africa. In a region with approximately 3,000 local languages, one way of improving compliance with COVID-19 measures has been the use local language information websites. In Chad, where more than half of the population lacks access to digital technologies, troubadours are even being recruited to help spread reliable information about COVID-19 transmission and prevention.

Conclusion

Some skepticism in political and scientific authorities is healthy because it encourages debate, contributes to policy improvements, and prevents societies from accepting decisions at face value. Yet, in a fast-moving pandemic, trust is critical to large-scale citizen compliance with public health measures, and strengthening it will require a range of interventions as cities and countries begin re-opening. Moving forward, governments will be working to finance health systems, support private businesses, and buttress social protection mechanisms, as well as fine-tuning social distance measures. But they must also invest in open information systems that account for educational and linguistic disparities, bring religious and traditional leaders on board, and provide professional training for security services to avoid human rights abuses. As shown in South Africa, partnering with opposition parties ex-ante to raise public awareness also helps create a united front and prevent skepticism about political motivations from undermining compliance.

Building greater trust in science requires both politicians and researchers to work together more proactively to identify sources of bias and set suspicions to rest. Scientists should be conscious of the practical implications their public health advice has for peoples’ economic livelihoods. In the case of COVID-19, this requires engaging with community leaders to produce nuanced recommendations for social distancing, contact tracing, and other measures, based on local contexts. More broadly, scientists need to interactively engage with communities to clarify potential misinterpretations of their findings and recommendations. This is critical, given that large segments of the public may not have a good understanding of the many protocols used to ensure research is credible and legitimate, including peer review, replication, and ethical standards. Actively being transparent about data sources and the scientific motivations for recommendations—and acknowledging when there is inadequate consensus for action—can also build trust. Politicians, for their part, can bolster citizen trust by affirming the independence and accuracy of respected scientific authorities, as well as personally and publicly following the recommended health practices.

Trust is much harder to generate than funding and equipment. Yet globally, bridging the trust divide between governments, scientists, and citizens is fundamental to recovering from the COVID-19 crisis—and to ensuring societies are resilient enough to cope with the next one.

Danielle Resnick is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategy and Governance Division and leads IFPRI’s Governance theme. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author.